Interzone: The Paintings of Christian Nielsen

Artist and Shoebox Gallery founder, Sean Smuda offers an elegant analysis of the mind-bending, gorgeous paintings by Christian Nielsen.

Editor’s note: We originally published this essay on Nielsen’s work in 2008, but Smuda’s examination is evergreen, still a beautiful read on the artist’s tricky, cerebral paintings. We’re pulling this piece up from the archives this week in Nielsen’s memory, after hearing news of the artist’s untimely death last week.

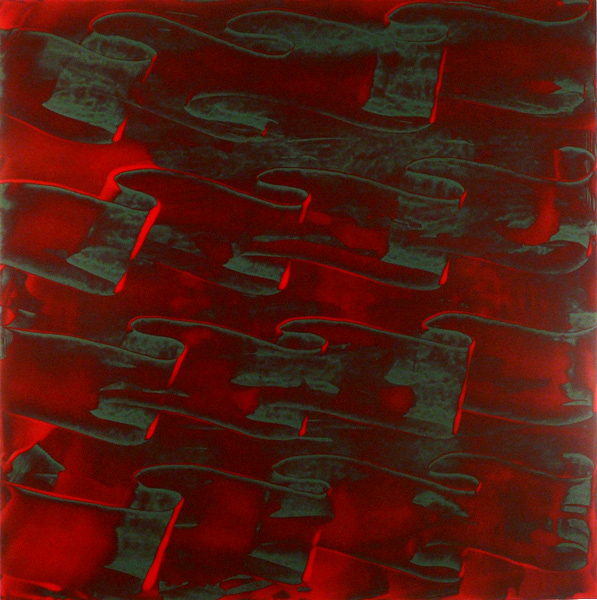

CHRISTIAN NIELSEN’S PAINTINGS EXIST IN THE OPTIC PLEASURE ZONE between literal and abstract expression. Their imperfectly repeating patterns and three-dimensional colors are familiar, yet alien. They subtly psychedelicize the windowpane geometries of Malevich and color interactions of Albers with an op-art emphasis on contrast. The scale ranges from the intimate, almost LP cover-size of 12”x12” to 40”x40”, portrait-size work which is suitable for meditation and rapture without nod.

Astonishing near-photographic details trail from the tightly controlled squeegees Nielsen uses to lay down the paint. No more than two layers of oils, with one color on each, are ever used. These self-imposed binary limits exponentially build the work’s optical fervor. The eyes undulate and pulse along translucent edges and scalloped shadows. Oil thinner and thickener help create peaks and valleys on super-flat Masonite or canvas stretched over board. These pieces bear no titles, just exploration that roams to fill the plane, working its void.

Nielsen’s color choices recall the fantastic, nostalgic, and exotic: radioactive lemon-orange Forbidden Planet dust; past-date Dead Sea foam flat, and Chinese pomegranate liquors. The resonance these colors spark from their gaseous, geographic, and mechanical architecture is quasi-sculptural. Such is the strength of this illusory painting, it is perhaps best to explore some ideas about perception and thought, rather than attempt to equivocate the experience of them with words.

It sometimes appears as though the process that brings the work into being has, itself, been captured as the painting, without the hand of the maker. This perception, in which the process of making becomes the artistic object of the work, is especially evident in the images which appear to depict the unraveled paper rolls. The mind does a double take at this (seemingly) immaculately conceived object. It is a truly po-mo satisfaction: a Möbius strip of image and referent going from without to within and back, ad infinitum. Like the way it is possible to see faces in most anything, we all have an innate ability to switch between abstraction and object, thought and perception. The pieces which fully take advantage of this ability make for the most readily appealing work: a painting with a ground of cocoa overlaid with a snow-powder white resembles a landscape of alpine drifts after dusk. However Nielsen does not wish to dwell in such pictorial-referential literality; instead, he exploits its inevitability beautifully and moves again to pure pattern.

______________________________________________________

Since the representational is not the primary facet of Nielsen’s work, the eyes are free to peruse the paintings’ physical primacy without being bound by the associations of resemblance and the burden of naming.

______________________________________________________

Since the representational is not the primary facet of Nielsen’s work, the eyes are free to peruse the paintings’ physical primacy without being bound by the associations of resemblance and the burden of naming. But, just as the artist exploits our mechanism for seeing form in formlessness, he also makes use of our minds’ persistent efforts to concretize the abstract. We’re left to question: Can these patterns have meaning, or must attempts to describe seeing the work amount to a personalized, associative laundry list? Maybe it doesn’t matter: Nielsen’s work continually pushes us to the limits of our efforts to make meaning of the forms we see, until language itself fails us. This way of seeing galvanizes a shift in the physics of our perception. Like walking through the site-specific gravity of a Richard Serra Torqued Ellipse, a Nielsen painting leaves one with a sense of being gently overwhelmed and levitated. On one level, we can’t help but demand, even create language to try to talk about what we see, but on another, the experience of his work is a wordless, purely perceptual one. It’s not an overstatement to say we emerge from its context sensitized to new possibilities of perceiving the universe.

Sometimes, particularly with Nielsen’s monochromatic work, patterned shapes are slightly built up from the thickened oil. One royal black cherry piece hovers between the organic and machine-made, like a library stacked spine-up and fanned out, suggestive on its surface of flattened leaves or curtains. Here the literal and the optical are almost interchangeable, but the image refuses to settle neatly in either category. Like the experience of an Aboriginal walkabout, naming and perceiving go hand in hand.

The between-state zone of Christian Nielsen’s work is a combination of its rich sensory immediacy and more removed conceptual nature, that of thought itself. Perception and thought interact and call each other out, one with language and concepts, the other more song or drum-like. Like Malevich replacing the Russian Orthodox cross on the mantle with his own painted square, Nielsen’s work may be enjoyed, at once, as a highly personal abstraction or something more essential, more rudimentary than that, rooted in the act of perception itself. His work presents us with this irreducible gift: the pleasure and task of viewing again, again, again.

______________________________________________________

CLICK HERE to browse through a collection of Nielsen’s tricky gems on mnartists.org

______________________________________________________

About the writer: Sean Smuda is an artist, photographer, curator of the Shoebox Gallery.