In the Time of Radical Realness

Introducing a series of writings by young disabled artists in Minnesota: from the simmering rage and grief to the swells of wisdom that come from living and making during a global pandemic

“When I think about access, I think about love. I think that crip solidarity, and solidarity between crips and non(yet)-crips is a powerful act of love and I-got-your-back. It’s in big things, but it’s also in the little things we do moment by moment to ensure that we all–in all our individual bodies—get to be present fiercely as we make change.”

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice1

Existing in the pandemic as a 20-something disabled person has felt like floating in the charged space of two repelling magnets; like making a home for myself in the silvery strings of a spider’s web, an inconsequential fly waiting to be consumed.

This tension has made itself home somewhere deep in my body, sinking farther than any pit in my stomach dared before. I can feel the bones in my hands grind against one another as I write this. My jaw aches from clenching it shut last night (and every night since March 2020.) I feel every dot of mist I breathe into my lungs and expel out of them. As I write, a fly buzzes against the lamp in my bedroom. The sound feels comforting.

20-somethings continue to be a key demographic in the United States as the pandemic rages on. We gather in massive groups despite warning; we keep masks jammed inside our back pocket or just under our noses and chins. Many of us refuse the vaccine—are suspicious of it, are denied accessible factual information, or feel it is not worth the risk. Those of us who are vaccinated ignore the news of breakthrough cases, lean into the sweetness of skin-to-skin contact, breath mixing together in a bar or concert venue, the feeling of laughter unrestricted. The risk is worth it.

For many of us, risk feels like an undeniable part of our twenties. This age is a point in our lives where we are finding independence for the first time, molding our identities. We feel drunk on the sudden rush of power, of possibility. Feelings of agency swaddle risk in the same hoodies that we used to wear in sub-arctic weather while our down jackets sat at home.

I remember this feeling like a watering mouth remembers its favorite meal.

“I was forced into more intimate relations with my body—relations that underscored my lack of control, thus my lack of civility, and ultimately my body’s radical realness.”

Carolyn Lazard, “How to be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity”2

20 was the age my body began to lose its battle against chronic illness.

Becoming ill shattered the image of myself and the world I had concocted in my head. It forced me to recognize my body as real, as vulnerable, as something I am forever bonded to. The “realness” of my body—how it is ever-present at the forefront of my mind, even as I lie in bed writing this with my dog asleep at my feet—forces me to reckon with my environment. The weight of this “real” body, a body heavy with sickness and pain, ties me to the realness of the world around me. It lays bare all of the systems I am operating under. It buries my feet, knee-deep, into the ground of the imperialist, white-supremacist, capitalist cis-hetero-patriarchy that is the United States.

There are parts of the pandemic that have forced all of us to grapple with the “realness” of our bodies. For some, this is the first time we have thought about illness as a collective issue, as something that exists and spreads within communities. In western culture, we tend to regard illness at an arm’s length. We see any illness beyond the temporary common cold as an unlucky hand dealt, or an individual burden. We also see it as something that happens to a specific type of person—someone weak or elderly. Someone else.

“The ‘personal misfortune’ approach to disability is also part of what I call the ‘lottery’ approach to life, in which individual good fortune is hoped for as a substitute for social planning that deals realistically with everyone’s capabilities, needs and limitations, and the probable distribution of hardship […] I think the lottery approach persists with respect to disability partly because fear, based on ignorance and false beliefs about disability, makes it difficult for most non-disabled people to identify with people with disabilities.”

Susan Wendell, “The Social Construction of Disability”3

When I read this passage by Wendell, I think of all the times I have confided in someone about my illness, and that person has responded, “I can’t even imagine.” I know it is meant to reflect their understanding of the gravity of being sick, but I wish that instead of saying, “I can’t even imagine,” to one another, we could say, “I believe you.”

The reluctance to imagine illness, to accept and engage fully with the fragility of a body, the mortality of a body, the thought of being at the mercy of your body, comes from a place of real fear. It is a fear that stems from a widespread societal denial of the fact that all bodies can become disabled at any point, for any reason. The denial that illness and disability are a natural part of life, that risk’s jagged blade can fall at any moment. It rests on the grounds that only certain people get sick, or become disabled, or are disabled. It creates an unspeakable distance between non-disabled, non-sick people, and disabled and sick people.

This dynamic has become even more apparent in the rampant denial of COVID. This must be a hoax, because it happens to people like them, not people like me. If I am safe because I am vaccinated, why would it matter if they are safe? This divide, this cling to individuality, affects the way we care for one another. What we will continue to learn as new variants emerge is that our safety is dependent on one another. This is something sick and disabled people have always known to be true.

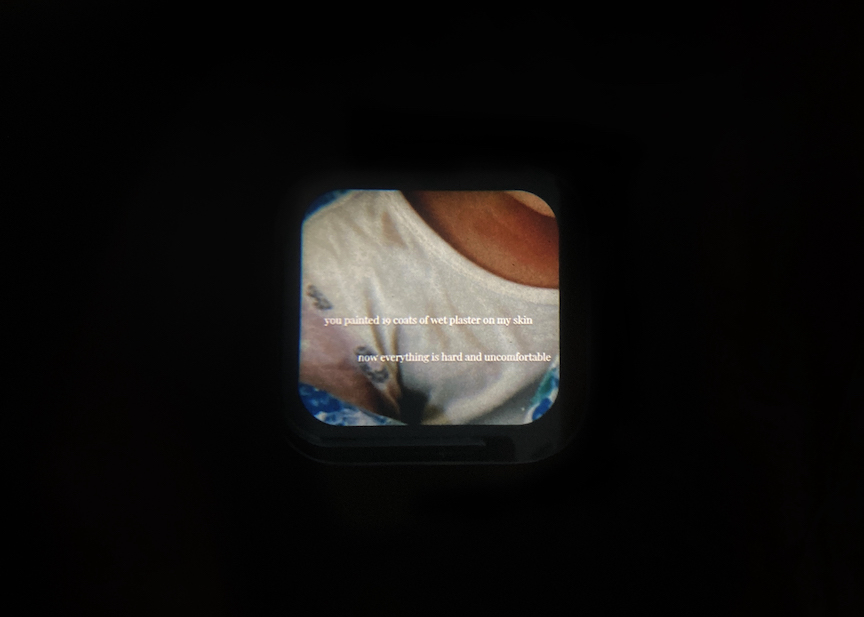

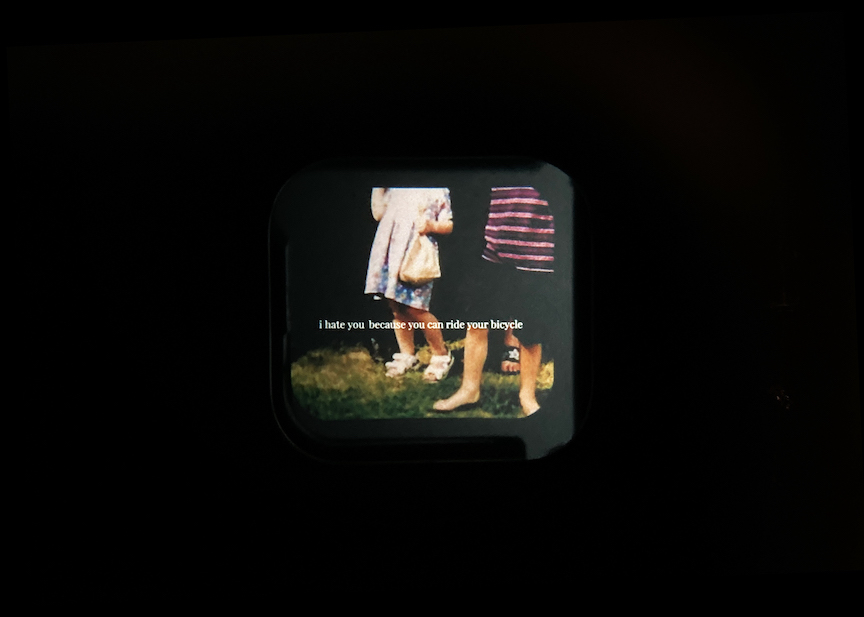

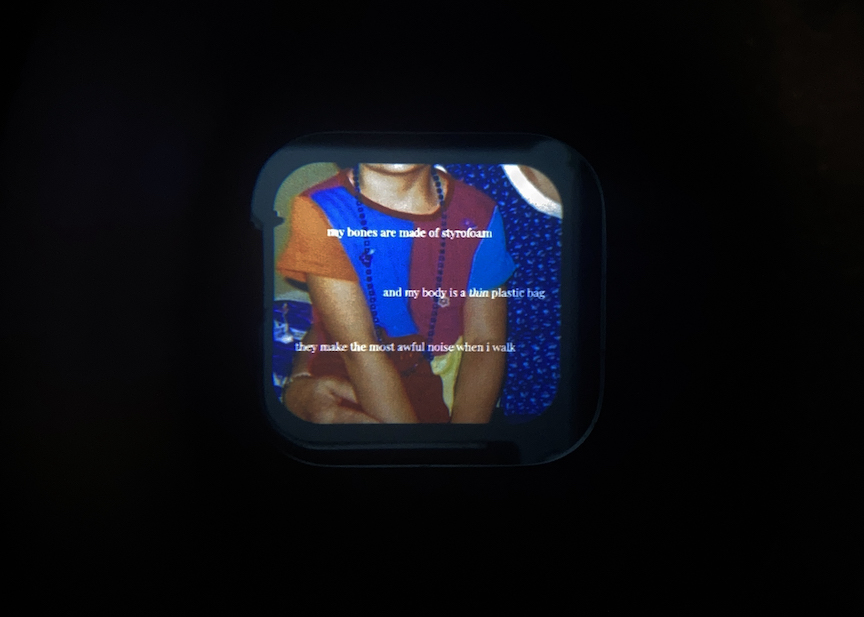

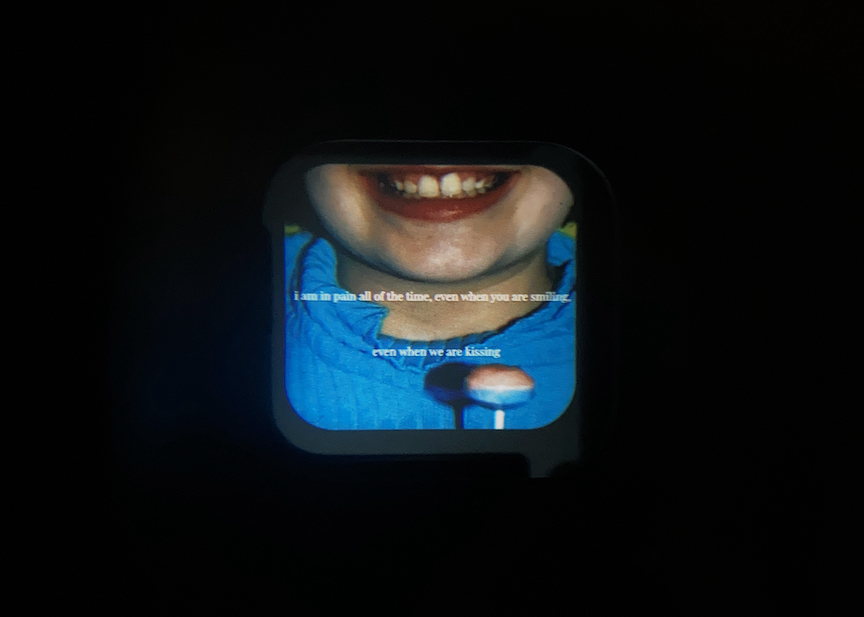

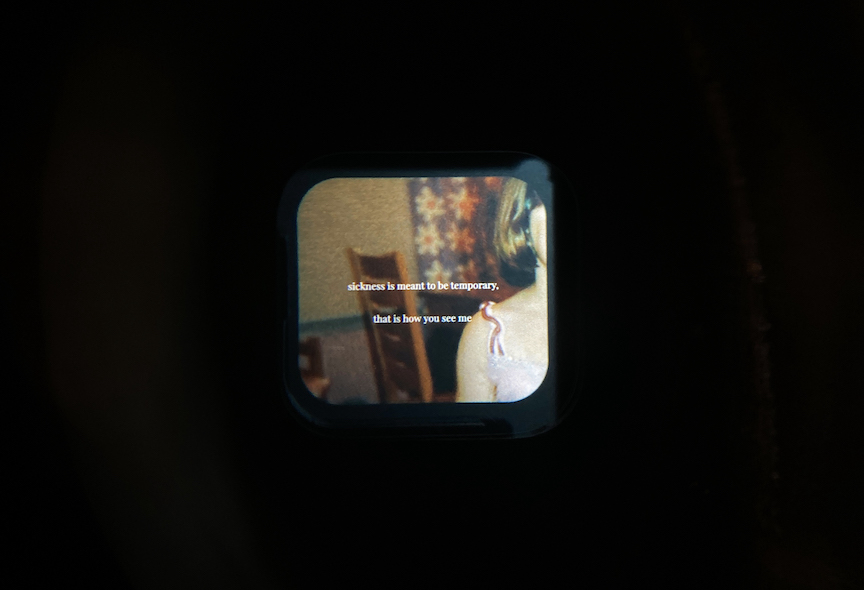

One of the last pieces I made before going into quarantine I titled Alone in the House of Illness, a reference to a moment in Johanna Hedva’s seminal work Sick Woman Theory. The piece was a response to the deep isolation I felt in my day to day life as a sick person. I was exhausted, experiencing invisible symptoms constantly, with few people around me who understood. I wanted to know if I could mimic parts of this experience for those around me, even if just for a moment. I created a custom View-Master reel with statements I had written based on my experience of illness. I took bulky, protective utility gloves and lined them with fine steel wool and fabric scouring pads. I asked my classmates to slide their hands into the gloves—at their own risk—and look into the View-Master toy that held my statements. Holding the object and pressing the lever down to reveal each image on the reel created a pins and needles sensation in their hands, one that lingered even after discarding the gloves, one that I experience on a daily basis.

I presented this on one of the last days of class before we went into quarantine, not knowing that my peers would soon experience isolation akin to my own. The gloves feel almost cruel, now, almost two years into a pandemic. I remember feeling closer with my peers after they experienced the work. Similar to the pandemic, this piece does not truly replicate the deep isolation that comes from illness. It simply offers a window into “the house of illness”—one that healthy, non-disabled people can pass or enter through as they please.

“The myth of independence is the idea that we can and should be able to do everything on our own and, of course, we know that that’s not true. Someone made the clothes you’re wearing now, your shoes, your car or the mass transit system you use; we don’t grow all our own food and spices. We can’t pretend that what happens in this country doesn’t affect others, or that things like clean air and water don’t bond us all together. We are dependent on each other, period. […] [T]he Myth of Independence is not just about the truth of being connected and interdependent on one another; it is also about the high value that gets placed on buying into the myth and believing that you are independent; and the high value placed on striving to be independent, another cornerstone of the ableist culture we live in.”

Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy, Interdependence, and Disability Justice”4

There have always been moments in my friendships with non-disabled, non-sick folks where I feel the distance put forth by my illness. It happens in small, daily moments: talking and walking in a group of people, suddenly left standing alone waiting for the elevator. It happens durationally: invitations to hang out become sparser and sparser the more times I have to cancel because of pain. If these common moments of distance are paper cuts—stinging, but ultimately harmless—the distance that has been created by COVID is a stake through my heart.

It has hurt, and still hurts, to see people I love with all my heart go to concerts, attend parties, go maskless or refuse the vaccine, when over half a million people in this country have died as a result of COVID. It has complicated my relationships with almost every person in my life. On a selfish, personal level, it stung particularly badly to see people who have witnessed the way illness has completely altered my life forever, who I have confided in time in time again, who I have cried with, who have seen me unable to move from bed—feel that risking a similar fate, or death, is worth getting a drink inside a bar or going on a Tinder date. I continually feel grief over the future I had planned for myself before I got sick, the many joyful important moments I have missed because I have been stuck in bed or in the bathroom. It makes my heart ache to know that this could happen to the people I love, too, and they are not protecting themselves or others. It hurts to feel as though even people I love and have intentionally shared my life with do not see all of me—both my illness, and my wholeness. It is a heartbreak like I have never experienced. It’s akin to whatever your first heartbreak was: that earth-shattering moment when you were 11 or 12 and realized that some other child that you thought hung the moon and stars didn’t even know you existed. The melodrama has faded but the ache remains the same.

“It’s hard to confess pain, because other people feel it or imagine it. Then they want to solve it. They will tell you the same solutions over and over: have you tried yoga? I had an aunt… They are desperate for the answer to the unanswerable, just like me.”

Sonya Huber, Pain Woman Takes Your Keys, and Other Essays from a Nervous System5

Almost two years into the pandemic, a part of me no longer aches as deeply. I understand. Before I became sick I never thought it was possible to live with this much pain. I couldn’t imagine a reality where a person’s body hurt this much and they chose to keep living. This pain has shown me that there are pains I will never fully know, that what I believe is possible does not matter because possibilities are happening whether I can imagine them or not.

The ache has been eased by being in community with other sick and disabled people. My friendships with other disabled folks in their twenties who are experiencing the same sort of grief and frustration have been my saving grace. Reading disabled authors, from the comfort of my bedroom, alone with my pain and my thoughts, has shown me the many gifts and joys of sick and disabled love. I know that this love will be essential in the times that are still yet to come.

“The Sick Woman is an identity and body that can belong to anyone denied the privileged existence – or the cruelly optimistic promise of such an existence – of the white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle-class, cis- and able-bodied man who makes his home in a wealthy country, has never not had health insurance, and whose importance to society is everywhere recognized and made explicit by that society; whose importance and care dominates that society, at the expense of everyone else.”

Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory”6

As I lay in bed, my sick little planet that I am the ruler of, I feel other “Sick Women” in my atmosphere. As I type, I feel the same keyboard felt by Johanna Hedva, Alison Kafer, Sonya Huber, Carolyn Lazard, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Mia Mingus, and many more. I feel the gentle warmth of my chronically ill friends, who do see me, who do understand, who share this experience and this magnificent disabled, sick knowledge.

The community felt in this atmosphere is what centers my rage and protects my world from being burned to a crisp with each fire that is lit every time I see someone without a mask, or another celebrity come out as an anti-vaxxer. It is this community, and this knowledge that illness has given me, that gives me the patience to wait for the people I love as their world shatters, as mine did at 20, as they accept their body’s “radical realness.” I have faith that they will meet me across the broken glass—as some of my friends already have at different moments throughout this year and a half. I do not cut my soft, sore, and swollen hands on the glass to guide them over. I allow myself to feel the rage, to scream when it feels right. I harvest that energy, and allow it to give me the compassion to wait for others to arrive. As I sit with this fire, not letting it consume me, I greet those around me with the knowledge that they feel just as scared as I had felt when I first became ill. I know that none of us have the answers to the questions that will follow us forward. I find comfort in the togetherness of the unknown. The future remains untold, but I dream from a bed that is big enough for us all.