In Practice: Photographer David Goldes

Lightsey Darst begins a new series of interviews with artists: first up, photographer David Goldes on his work in the studio and in the classroom, the vagaries of time and ambition, and the importance of paying attention.

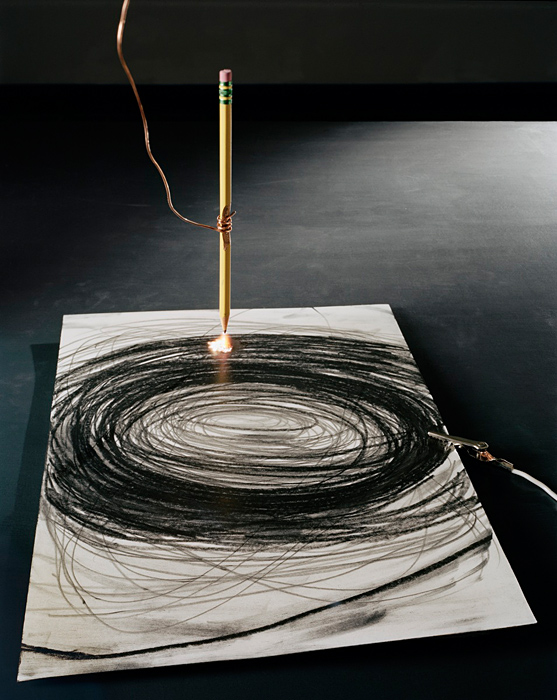

David Goldes is an artist and teacher based in Minneapolis. His awards include fellowships from the Guggenheim, McKnight, and Bush Foundations. His work is widely collected: look for his science-inspired photographs at MoMA, the Whitney, the Walker, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others.

What is work?

David Goldes

Now, the easiest answer to “what is work?” is the un-poetic answer a physicist or mathematician might give. It is the force needed to move an object a certain height, measured—and here’s where the poetry comes back in—by joules. There’s lifting and hemming and hawing and disappointment but maybe, just maybe, there is the unexpected, unplanned surprise, too, and what one discovers by paying attention. Of the many kinds of commonly defined work that I do, the two biggest are teaching at an art school and making things in my studio. No piloting of jet planes or the challenges of tending a sick family member or driving across country, but by teaching and making, it’s what I don’t know, what I don’t expect, what I sometimes can’t even recognize that offers me the energy to lift weight to a certain height.

How do you spot a promising young artist or student?

David Goldes

I love the first day of a class and my foolish assumptions about who will be the strongest students in a class. Foolish, because by now I know I am almost always wrong. What later becomes clearer is who the hungry ones are—hungry for knowledge, for clarification, for being seen. And they’re the ones that do more, want more, who are present and who understand that they are in charge of what they are doing. They are the ones who somehow can deal with the enormous sense of vulnerability and doubt that all young artists and students face. Many run from this rawness, some tolerate it, and others amazingly learn and grow in the face of it. I admire them greatly.

Lightsey Darst

I love that you answered this question, because you and I met in the halls at Minneapolis College of Art and Design, both teaching (and struggling with) young artists and their power and their vulnerability and their fear and their promise and their responsibility and irresponsibility and all the rest of it. Teaching, I was always thinking about who I was when I was young, how I must have seemed to my own teachers. So, that brings me to ask: Who were you when you were young? I’m imagining a shy, precocious kid—Milo from The Phantom Tollbooth. Am I on the right track? And what could you do for this kid, for young David, if he showed up in front of you now? Your bio shows an MA in molecular genetics from Harvard, and then your next move is that zigzag into art—your first group exhibition at the Southwest Biennial, then your MFA. Is there a push someone could have given you that would have directed you towards art earlier? Or did you already know what you were doing?

David Goldes

It’s a great challenge to think of myself at the age of my students, as each day the gap widens. However, you are right about my being shy. Very shy, in fact, though I had a freshman English teacher in college who made me feel like I was alive and worth paying attention to. But by then I had been on the post-Sputnik (now that should date me!) push in American science. However, my mother had urged me to go to poetry readings in college, and fortunately I was studying at SUNY Buffalo, which had a remarkable roster of literary folks, many from Black Mountain: Creeley, Charles Olson, John Barth and others who garnered gigantic audiences that swept me in from across the campus. Slowly my interest in science waned and the great positive outcome of paying attention to everything that is afforded by shyness moved me into the questions addressed by art.

What can’t you do in your art yet?

David Goldes

In Morocco this winter, I thought I should stop making art and try to invent a photo-degradable plastic bag. Outside of Fes or Marrakesh there are heaps of garbage by the side of the train tracks that go on for miles and miles mostly made of red or blue or clear plastic bags which will be there until they are moved to somewhere else, the ocean or outer space.

Lightsey Darst

In Sri Lanka I was told these are called siri-siri bags, from the rustling sound they make, and they are considered to be so useful around the house that you have to specifically decline them in stores. Whenever I end up with a heap of them after buying, you know, seven things at Target, I wonder what the cashier is thinking. But the question I really want to ask here is how this would intersect with your art, or rather why you thought of this in answer to my question. Does art border on this kind of usefulness to the world for you? If you had an idea for how to make a photo-degradable plastic bag, would that overtake your art practice? I’m thinking about how your work does seem in some way useful—how in your Water series, say, you are reminding us of these natural principles (of surface tension, of wicking) that we often learn about as kids but that we may forget go on working in our adult world.

David Goldes

Perhaps it’s a matter of the kind of impact one can make. The art world is so insular and the heaps of plastic bags so enormous. But but but…I know I am not really able to invent a photodegradable bag—I will leave that to someone else even if the challenge haunts me a bit. I do what I can do—even if the audience is small. At least there is something of an audience! Hopefully my work can contribute to an experience of wonder, beauty, and understanding. I am trapped and liberated by the terms I have chosen.

Current color obsession?

David Goldes

None really, but I could read William Gass’s literary color obsession, On Being Blue, over and over. Or each issue of Cabinet magazine has a wonderful digression on a specific color. David Byrne wrote a great piece on the history of pink and how it was once a man’s color.

What’s the best metaphor for time?

David Goldes

Great question. Rivers never did it for me. How about a Mobius strip made of water that hangs in space? Slippery, easy to fall off of, repetitious but also different each time, no beginning or end, and you don’t know you are on it…

Lightsey Darst

So, the difference between a river and this thing you’re imagining—your Mobius infinity pool—is in apparent motion, more or less? That, unlike a river, the Mobius strip may not seem to move? I’m curious because you’re a photographer, literally, and yet your photographs often pull against their own instantaneity—they testify to the longer time over which you created the circumstances of the photo. Is the instant satisfying in itself? What is an instant?

. . . I’m looking at some work that strikes me as unusual: your Fire Pond series. Here the photo is no less an instant, but I understand that it’s one instant in a long sameness. The instant has a different feeling: instead of putting me at exactly the right place and exactly the right time, it reminds me of how I’m not there. I’ve fallen off infinity.

David Goldes

I have always hoped that the photographic instant, which can be a 1/10,000 sec or 20 minutes, (in my hands) must also function to suggest, point, help us move to consider the time before and the time after. Just as the space of a picture is ripped out of the world, what is beyond the frame needs to be somehow implied and considered. I would like to make a feature film in one picture. Isn’t that what poets do?

What is the most important scientific principle?

David Goldes

It’s not a specific principle, per se, but the scientific method itself is most important: i.e. pay attention to what you are observing, throw away your assumptions about what you expect to see; be open to impossible explanations.

Editor’s Note: Lightsey Darst is conducting a series of interviews with artists, writers, and other interesting people. Look for repeating questions across the series. If there’s someone you’d like to see her interview, please let her know: lightsey(at)lightseydarst(dot)com.

Lightsey Darst is a writer, critic, and teacher based in Durham, NC.