“Imitations” at Soo VAC

This high-concept show has artists imitating each others' works. Each of the 10 artists was charged with the task of copying another artist's work, producing a daisy chain of original imagery and more or less faithful copyage of same.

Among the great pretenders of aesthetic creation — Borges’ infamous Pierre Menard, the notorious currency forger J.S.G. Boggs — it may be Wyatt Gwyon who most deeply probed the stakes of imitation. The central character of William Gaddis’ 1955 novel The Recognitions,” Gwyon creates immaculate fabrications of Flemish masterworks, harnessing his technical mastery to a studied ability to channel the artists he mimics. But his deft impersonations simultaneously prove depersonalizing: in imitating the other he confronts the loss of himself. An artist without qualities, he raises the specter of works without authors.

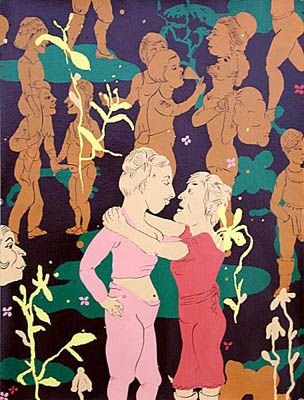

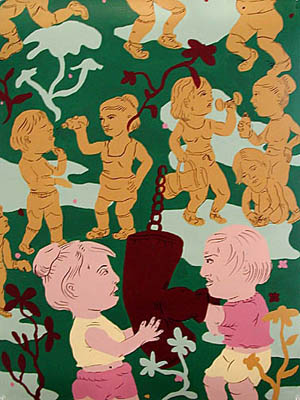

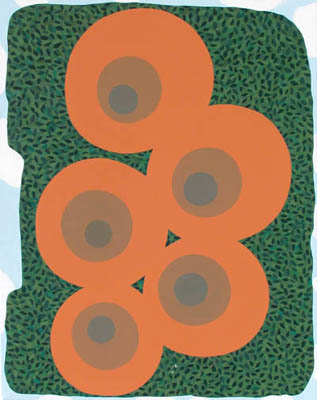

Such is likewise the preoccupation of the SooVac show “Imitations,” which pairs off ten artists from Michigan and Minnesota, challenging each to produce both a work of their own and one created in the style of their opposite number. Most of the artists skirt the radical prospect of complete submission to the style of the other; what results instead are various dialectical fusions through which the artists find formal or thematic common ground. Such is notably the case in the dressmaking of Alexa Horochowski and Sue Carman-Vian, and the panty and swimsuit paintings of Frank Gaard and Kai Kim; Cristi Rinklin and Dana Bell’s exchange is a provocative struggle between depth and surface. In each of these cases, the artists seem to work through the other’s style, instead of working in it. Mary Esch elects to eschew Jenny Schmid’s style altogether, in favor of a pencil-sketched “ode” to Schmid’s “Strongest Girl in the World” that completes the narrative of the titular character’s power lift: in return, Schmid capably reproduces Esch’s “Garden Party No. 2,” while substituting her own pugilistic characters for the Esch originals.

Most nearly fulfilling the show’s dictate of self-effacement is the encounter between Thomas Rapai and Bruce Tapola. A parking lot landscape by the latter assumes both the horizontal style and the bleak spirit of Rapai’s oils of anonymous modern structures; Rapai opts not to attempt a reproduction of Tapola’s “French Camp” (the show’s highlight, it is a striking arrangement of cartoonish cosmopolitan women painted amidst a rustic lakeshore setting), but rather extracts typical colors and signature treatments of movement from works exhibited by Tapola in the past. For Rapai and Tapola, less personal intervention in the other’s style means more interesting answers to the question of (the death of) the author.

Overall, it is tempting to measure the “success” of all these imitating artists by the degree of similitude they achieve, but that standard is obviously unfair to the works themselves; it reduces the curatorial conceit of “Imitations” to a technical game. Nevertheless, to do so highlights the temptation to invest the work of another with a little bit of oneself — and thus reveals the persisting strength of authorship’s allure.

The Soo Visual Arts Center is located at 2640 Lyndale Avenue South in Minneapolis. Show dates are Dec. 2 – Jan. 26.

www.soovac.org