Imagine, Mr. Speaker, a World Without Balloons (Part 1)

Americans have always seen civic life as happening on a stage, each citizen performing democracy. But too often we forget to act, to perform our roles - we think of democracy as a noun instead of a verb. Sam Gould offers the first of a two-part essay on the art of purposeful disruption.

“Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or dreamed that one possessed. Yet, it is only when a man is able, without bitterness or self-pity, to surrender a dream he has long cherished or a privilege he has long possessed that he is set free — he has set himself free — for higher dreams, for greater privileges.”

—James Baldwin (from “Faulkner and Desegregation,” published in Partisan Review, fall 1956)

There are many paths to citizenship — each as unique as ourselves, which must be repeated daily, each morning, like a rosary. A rocky terrain clutters the paths between the triangulated space separating insincerity, irresponsibility, and the irrational. We walk these paths, attempting to gain the attention, or assistance, of those around us. Depending on one’s vantage point or proximity, our intentions or actions can be easily confused. When “going public,” we tread this terrain warily (or perhaps more accurate, haphazardly). We easily become enamored with the familiar, with our proximity to the experiences closest to us. It’s easier than venturing out into parts unknown. I’m trying to work out the equation that best suits democratic space, in regard to our contact and distance from one another. How much friction is needed for our lives to affect one another with positive force? How much is too much? When do our collisions, considered poorly, erode the skeletal system that is our civic body?

Americans have always seen civic life as happening on a stage, each citizen performing democracy. The Constitution is itself a set-list for a production constantly in motion. Quite often we forget to act, to perform our role; we think of democracy as inherent, a noun instead of a verb. In those moments, it’s as if we’re merely living out our days, our relationship to democracy as elemental as the natural landscape, as habitual as breathing, instead of what it is – a craft. But, we breathe in unison, our bodies, the trees, the water and sky. And now we’re lost, on the decline, without one another. It’s worth remembering: this is all an act, this becoming a public, this collaborative formation of democratic space. If we forget that fact, we lose control of the narrative. We get confused as to where we are, or worse yet, complacent, by becoming all too aware of where we are “right now.”

As the narrative of democracy is complex and boundless, it’s crucial to stay in book and on the page. While broad, that page is our commons — we congregate there around a radically simple storyline that suggests, through our associations (our relationships), we are, each of us, attempting to construct a common good.

I’m okay with this Aristotelian notion of “good.” The idea gives me pause, and in the space of that hesitation I sense its usefulness. This notion of a common good, and the problems and complications it carries, activates a device which allows us to see one another through our shared experiences. But this machine of common good only works if we agree to open it up, to allow space for tinkering and new ideas.

Aristotle’s contention was that these collisions of subjective experience are the ground for active formation of a polis (city state). Without those collisions of selves, we’re venturing off the page. Those relationships and the debris they leave behind comprise the very stuff that makes us citizens. The less we associate, the less we collide, the less democratic we are. Furthermore, I’d argue, the more we attempt to hide the effects of our processes of association, the less democratic we are able to become, in that those effects articulate a kind of democratic cartography — the lines and words, sometimes caricatures of our disagreements and common cause, made visible on the page. To be plain about it: when we hide our faults from view, we’re doing ourselves and each other a disservice.

IN THE SPRING OF 2001, thanks to a friend whose records I was putting out at the time, my partner Laura and I found an old, inexpensive house to rent. It was just down the road from the apartment next to The Jockey Club I had been living in since I moved to Portland two years earlier, prior to Laura’s move out West. The house, about 100 years old and chalky yellow in color, was on a quiet street, albeit one with a few dots of eccentricity. Take our landlord, Robert (but everyone called him Poo); he repaired radio towers. At the time, he housed his shop in the garage attached to the house. When we moved in, parked in the driveway there was a massive, anthropomorphically-shaped vehicle — construction-yellow with flaking paint that revealed the steel under its coat, a lumber mover. Not intended to move mere pallets of wood, this machine, 12-feet tall, was used to move trees once they’d left the logging camp and needed to be moved around the mill. Poo, not infrequently, would drive the lumber mover around the block, allowing people to hop on and off for a lift as he went. In the days after September 11th, I recall a long conversation with Poo on our front stoop. He was incensed at what he saw as a lightning-quick fascist turn in America, starting now with the new FAA rule that passengers couldn’t bring box-cutters onto planes any longer. At 24, and not being the box-cutter-carrying type or a born-and-bred Pacific Northwest libertarian, I found it difficult to grasp Poo’s vitriol and sense of impending doom. While I still don’t carry around box-cutters, the 14 years that have transpired since this conversation have eased me warily into Poo’s corner.

When we moved into that house, it was the tail end of the rainy season. We had been told that Jimmy, our neighbor directly across the street from us, took the winters off, traveling to warmer climates (usually in Asia), to avoid the months of purpley-grey wetness. Jimmy was spending that rainy season in Vietnam; he’d enlisted in the early years of the Johnson administration, and it was his first visit back since returning home from the war.

On an early spring day, one of the first that was consistently sunny and warm, I went to Everyday Music to sift through the 50 cent record bins. It was an activity that, in those days, hadn’t yet been completely marred by Portland hipsterdom, wherein you’d be pleased but not shocked to find slightly scuffed original pressings of Terry Riley, John Fahey, Aretha Franklin, or some Smithsonian Folkways field recordings. On this afternoon, I returned to our old house with a double LP of Mississippi John Hurt. As I bounded up the steps to show Laura my find, I could see her, through the screen door, towards the back of the house: she was sitting at our massive kitchen table across from a man wearing a huge, multicolored headdress (what turned out to be a headdress of a Vietnamese shaman), a bottle of yellowish gold liquid between them. Floating in the bottle was a young though not altogether small snake. Jimmy had returned from his winter escape and had come over to introduce himself. I put on the Mississippi John Hurt record and joined Laura and Jimmy in a toast with the Vietnamese moonshine he’d brought back home.

Jimmy, following his war experience, wanted to remain outside the system as much as possible, but not outside the world of public life. He did all he could imagine to not take part in what he saw as a lot of lockstep, follow-the-rules bullshit. He and Poo were old, dear friends. Jimmy worked as a carpenter — he was quite good — and plumber. Only taking cash or trade for his services, supplementing his income with his veterans benefits. Jimmy adhered to a sort of measured anarchy in both his life and craft. The exterior of his home looked like a well-ordered outsider artist carnival, a gigantic four-foot-tall severed hand with an eye painted on its palm served as a sort of weathervane on the roof of his garage. And that was just one example of the type of display passersby might find at his place. In the front yard was a dead spruce tree. Tall and barren, it seemed almost sanded down, petrified. One day, I returned home to find that Jimmy had climbed near to the top of its 25-foot spar and was pouring red paint down its trunk. Onto the end of each thick, spear-like, branch he impaled severed mannequin heads, placing masks of Bush and Cheney (as well as five or six other core advisors for the administration) onto each one. For good measure, he added a little extra red paint around the neckline of each. To finish things off, he nailed a handpainted sign to the lower half of the truck which read: “Tree of Shame.”

Having Jimmy as a neighbor made me feel safe.

Jimmy was an early member of the Portland chapter of the Cacophony Society. When I moved to Portland, their “Yellow Plan,” a nod to the Dutch anarchist collective Provo, was just fading into memory: in dual reference to a failed city program, they began, and encouraged others, to paint anything they wanted to share yellow, and then to place it in a public space where it might begin freely circulating. When I arrived in town, it was not unusual to see blenders, whole couches, slathered in yellow paint and sitting along the side of the road. Jimmy’s involvement in Cacophony made perfect sense. While its progression and associations over time and into The War on Terror, similar to the parallel legacy of Burning Man, is problematic, the origins of the Cacophony Society are steeped in Do-it-Yourself anti-establishmentarianism.

The Cacophony Society rose from the ashes of the Suicide Club, a small, semi-secretive anarchic group formed in the late 1970s in San Francisco that planned events for itself which challenged notions of acceptability, form, and perception in regard to the day-to-day: climbing bridges, attempting to provoke a cop to throw a pie in your face, that sort of thing. The membership card to the club read:

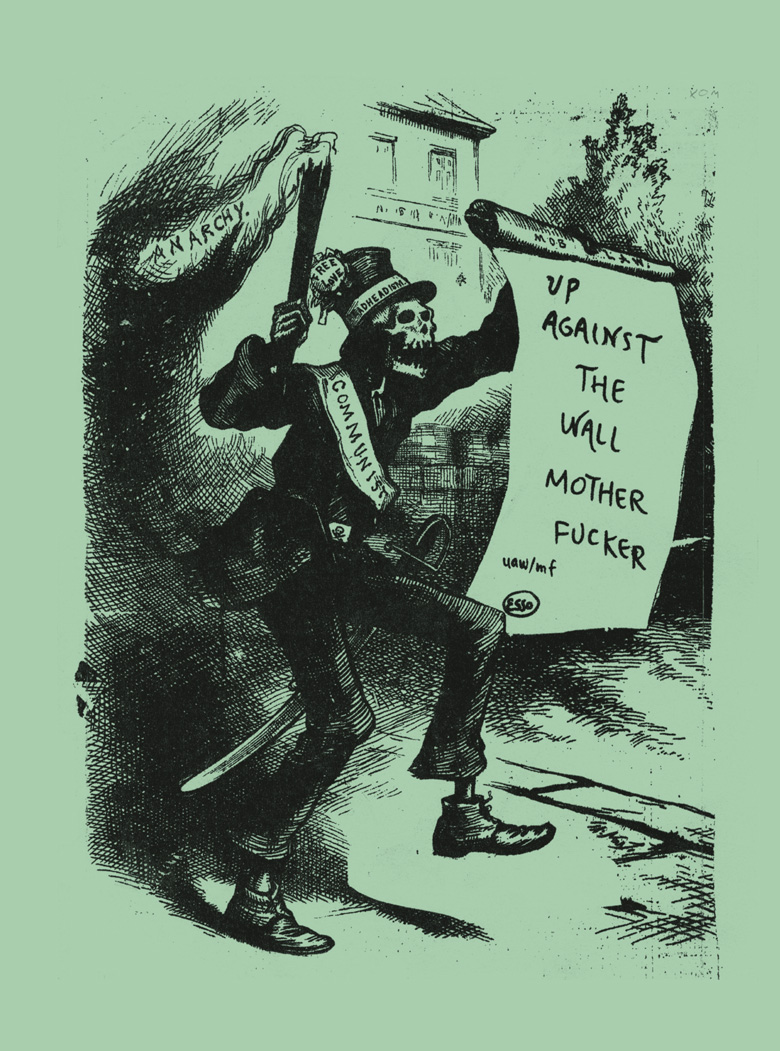

The Suicide Club is part of a long tradition of non-issue-based political groups, such as The Diggers (in the Bay Area) and the International Werewolf Conspiracy / Up Against the Wall – MOTHERFUCKERs (Lower East Side of NYC). While these latter historical examples were more concerned with what might be considered overtly political issues, you weren’t going to see representatives from the Motherfuckers at a political rally or protest march. Their social concerns were elemental, pointed, and bedrock; their operating strategy, simply F.U.S. (Fuck up the Structure).

With the federal backlash towards groups like The Diggers and UAW/MFs, and a retreat towards more isolated, intentional living scenarios, the Suicide Club, and later Cacophony, are a natural psycho-political progression of this lineage. Formed in the depths of Carter’s American “malaise,” and solidified in the fog of Reagan’s brainwashed, neo-Eisenhower “shining city on a hill” rhetoric, these groups were concerned, tactically, with what Felix Guattari called “molecular revolution,” stating:

“Yes, I believe that there is a multiple people, a people of mutants, a people of potentialities that appears and disappears, that is embodied in social, literary, and musical events…. I think that we’re in a period of productivity, proliferation, creation, utterly fabulous revolutions from the viewpoint of this emergence of a people. That’s molecular revolution: it isn’t a slogan or a program, it’s something that I feel, that I live….”

This tactical decision — first by The Diggers and UAW/MFs, and followed by, to a more “molecular” degree, the Suicide Club and Cacophony in a much foggier, if not far more energetic and chaotic, sense — to uproot the demonstrative and provide an urgent, anarchic vehicle-in-action of The Possible is a legacy we’re deeply (and, arguably, deeply problematically) living today. Presently, in the age of Snowden, drones, and purchase tracking, what means do we, as individuals, have at our disposal with which to fuck up the structure? We’re hardly aware of said structures, their foundation or desires. Digging, digging deep and radically clowning around has proved, for some, to be one simple, obtainable, and infectious tactic.

Once I saw Jimmy and a team of friends stacking pet store birdcages filled with pigeons onto the back of his flatbed pickup truck. When I asked him what they were all up to for the day, he replied that they were heading down to Tom McCall Waterfront Park for a barbecue. By grilling Cornish game hens against the backdrop of their cubed tower of caged pigeons, Jimmy and his associates planned to extol the virtues of “free food” and the abundance that we ignore in the world around us. Gnawing away on meat and bones, Jimmy and his Cacophony friends set out to offer up free samples to passersby of “pigeons” they’d captured in the park and barbecued on the spot as a lesson in self-reliance: “Never go hungry again!”

I learned a lot from Jimmy’s daily ethos and his seemingly slapdash tactics. If nothing else, his example made me patently aware that the tools I need to address the failings I see around me are available, first and foremost, right here — in the triangulated space between myself, my friends, and our shared creativity. After being stuck in the jungle and shot at in his youth, Jimmy was determined to never engage the system directly again — too much friendly fire. But he’d be damned not to attempt a counterassault through the backdoor.

Inevitably, the more complicated my life got, the more I began to question. In the summer of 2003, we moved away from that yellow house and spent a year in Chicago before returning to Portland. In the intervening years, after our return and before our final move away which brought us to Minneapolis, the city began to change quite a bit. Portland was still oversaturated with bearded men wearing Elvis jumpsuits at downtown karaoke joints and guys riding unicycles while wearing a kilt, a Darth Vader mask, and playing the bagpipes.

But the urgency of these actions felt less and less revelatory to me. They revealed less of what was possible than they did a retreat into shtick and pedestrian showmanship. With the wars in the Middle East going on and on, snipers training their guns from rooftops at those of us marching; with my relationship to The War on Terror and its aftereffects, through harassed activist friends and with the stories and trauma of returning veterans, I began to have something of a crisis of confidence in the political potential of hijinx. I still had a good amount of affection for it, I just couldn’t engage in it myself without some kind of direct meaning and purpose with which to associate it. Anarchic pranks for their own sake started to seem pointless — or, more accurately, insular and concerned only with the moment’s disruption, desirous of no debris to remain at the scene that couldn’t be swept up immediately by those already in attendance. I kept asking myself, “to what end?”

Not long before we left Portland, I was sitting on my friend Matthew’s couch, as always, perpetually soggy from the winter rain, as we relaxed with some drinks in front of his fireplace. In the smoky air, I recall lambasting yet another impromptu bike jousting tournament that had shut down the Broadway bridge earlier that afternoon, for no reason other than it was a fun thing to do.

Days before, Aaron Campbell, an African-American man, had been shot, killed, and had a police dog sicced on him. I wondered then, and I still wonder: if you’re going to shut down a major river crossing, why not do it in parallel with an event like Campbell’s death, to make visible the sorry situation at hand? Throw the irrational in the face of the irrational. You can still dress as knights and knock one another off your bikes with PVC piping, but shut it down for something more than your desire for the world to be more “interesting.” Shut it down because the world is not merely boring, but all too often deadly.

Born in New York City in the mid-1970s, Sam Gould is the co-founder and editor of Red76, a publication that materialized in Portland, Oregon in the early 2000s. Instrumentalizing ideas around publication as a social force, Red76 works towards the formation of publics through the implementation of ad-hoc educational structures and discursive gatherings. While these actions are often situated in what is called “public space,”– such as street corners, laundromats, taverns, and the like — the pedagogy of their construction is meant to call into question the relationships, codes, and hierarchies embedded within these landscapes from one incident of publication to the next. Along with a desire to illustrate the shared experiences of an accumulated public, Red76 works to ask: What is a Public? and What is it Good For? Gould has taught within the graduate department for Social Practice at the California College of the Arts and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has written, as well as lectured extensively within the United States and abroad, on issues of sociality, education, and encountering the political within daily life.