Hip-Hop and Race: 4 Things and 5 Things

Toki Wright, producer, musician; and Peter Scholtes, writer, think about hip-hop--which has been a delightfully complicated meeting ground for a score of cultures and subcultures. This piece ran originally in spring of 2006--have things changed?

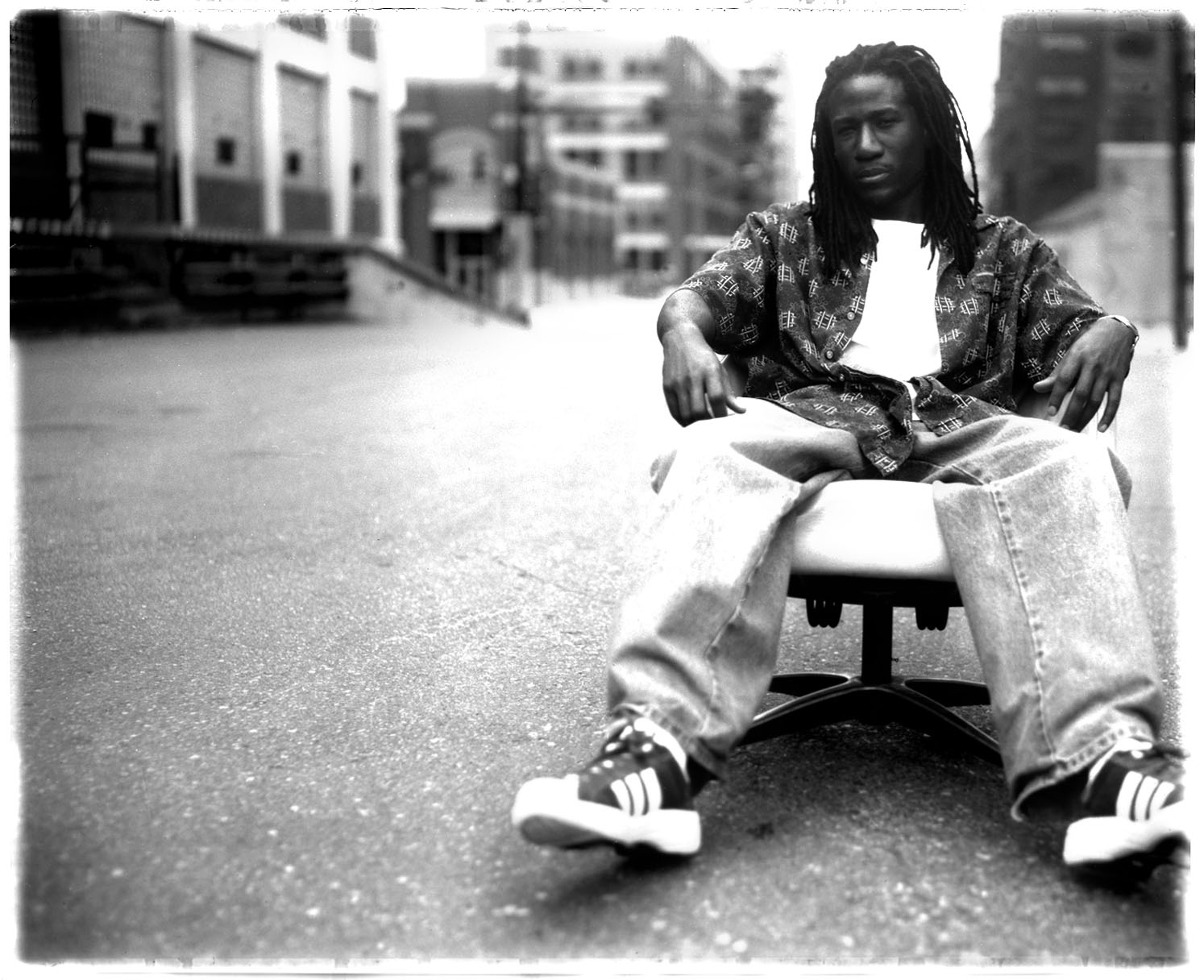

Minneapolis-based Toki Wright has been involved in worldwide connection as a community organizer (www.yothemovement.org/ ), emcee (The C.O.R.E./APHRILL), freelance writer, volunteer, creative writing/performance teacher, and poet. His work has been featured on NBC, MTV, WB, and in Independent Film. He can be reached at www.tokiwright.com or www.myspace.com/tokiwrightmusic

Peter S. Scholtes writes about music and culture for City Pages, a weekly newspaper of Minneapolis/St. Paul. His articles have appeared in Spin, Vibe, XXL, and Blender. He has lived in seven American cities, including New Orleans, and has loved rap music for 20 years. To read his hip-hop writing, visit complicatedfun.com/hiphoparticles.

4 Questions on Race and Hip-Hop in the Twin Cities

By Toki Wright

RACE. I either just got your attention or totally turned you off.

HIP-HOP. (Insert previous statement here.)

BOTH OF THESE are two very touchy topics of talk. I find it hard to have a discussion about one without the other in the Twin Cities. We live in a day and time where hip-hop is being recognized globally in places that weren’t even given a star on the map before. Living in the Twin Cities we are confronted with both race and hip-hop on a daily basis.

For clarity’s sake I should introduce myself. I am a 25-year-old African-American Minneapolis resident. I have been producing hip-hop shows locally for youth since 1998. I’m also a performer and speak often about the racial dynamics of our local scene with students, artists, and the others in the general public. My personal belief in the need for equality is not always agreed with. My answers do not exist to be final and my questions are meant to be open-ended. This being said, I think that the issue of race and hip-hop in the Twin Cities is not an issue that can be summed up in 700-1000 words.

Rather than writing a traditional article, I chose to internally debate four questions that come up often locally. It is my hope that these questions and responses will open up further conversation. While you are reading this I will clean out my inbox for the hate mail.

The racial segregation in hip-hop is a Minnesota thing, right?

Yes: In the Twin Cities there is something called “Minnesota Nice.” What this means is that unlike other places where people are more up-front about disliking you solely because of your race, people will act as if they accept you until you turn your back. This spills over into the hip-hop world.

No: Go to a hip-hop show in any city in the United States. Depending on the night, depending on who’s performing, and depending on who the promoter chooses to promote to, you could have a number of segregated outcomes. The truth is that some promoters just don’t like certain groups of people at their events for numerous reasons. When they are in control they can shape the events however they want.

Is the internet hurting Twin Cities hip-hop race relations?

Yes: The internet provides a space for people from all walks of life to make both blatantly and covertly racist statements without being censored. In the World Wide Web you can also hide your identity while making these statements so that you are not physically dealt with at every rap show for the rest of your life. The internet has become a catalyst for the physical and emotional disconnect between members of multiple backgrounds in our hip-hop community. The written word is difficult to judge because it can often lack that emotion. In turn people can develop whatever opinion they decide.

No: Many necessary conversations have arisen because of the internet’s ability for you to voice your opinion uninterrupted. Though ignorant comments are made, the constructive responses to the comments can be viewed by a wide number of people.

Do only white rappers get good shows?

Yes: It would certainly seem that way if you don’t take into account the amount of mixed-race artists living in the Twin Cities. Many of the “white rappers” have had the opportunity to follow in the footsteps behind a multitude of local performers who have paved the way. Also a lot of white kids don’t feel comfortable in a room full of kids of color just as much as a lot of kids of color don’t feel comfortable in a room full of white people.

No: Many of the “white rappers” get good shows because they have put in the effort and are consistent and persistent. You will see this to be true with many artists of other nationalities that understand their audience, create a workable business model, and stick to their plan. (i.e. Swisha House, Murs, Immortal Technique)

Is the Twin Cities being disrespectful to the “Streets”?

Yes: First there is a direct relationship between people of color and street culture. A lot people frankly do not care whatsoever about what happens in the inner city. When people from the streets, mainly people of color, talk about their issues of being ignored, placed in impoverished neighborhoods, police brutality, the sale of drugs, etc, outsiders may choose to ignore those realities. This is especially relevant because there is a direct benefit to privileged communities for this struggle.

No: Many of issues written above exist in all communities at different levels but there have been countless examples of “Street” culture that have had negative results on the community at large. Also due to media’s thirst for heroes and villains they tend to pimp out the “Street’s” pain for the gain of a good story. So when people of color bring to light negative issues they make themselves an easy target.

If we look at quantity it is rare that you will find a hip-hop event in the Twin Cities that is dominantly non-white. What does this mean? Do people of color no longer care about certain types of hip-hop culture? Do white kids appreciate the culture more than youth of color? Is there a racist overtone in Twin Cities hip-hop? Yes and No. The discussion is left up to you. What’s your version of the truth?

Tell me something good: 5 Things to Remember About Race and Hip-Hop

By Peter S. Scholtes

1. Race doesn’t exist.

This is easy to forget, partly because racial categories are ingrained in our thinking, and reinforced by our language. But I bet if you go back in your mind, you’ll remember a time when race didn’t exist. You were a kid, just playing with other kids. Race was imposed, just like racism.

The word “race” began being used in most of the senses it has today in the 1500s. It meant “species” (as in “human race”), but also a line of descent. A third, more problematic meaning combined the first two into one, and applied to a group of human beings. The ambiguity there fueled centuries of racist pseudo-science (see Raymond Williams, Key Words, Oxford University Press, 1983).

Today the mapping of the human genome has made the notion of different “races” transparently absurd. As a biologically meaningful concept, it hangs on by the barest of threads: Certain genetic traits appear to cluster along “racial” lines when it comes to disease. Blacks, for example, are more likely than whites to get lung cancer from smoking cigarettes. Like obvious differences of skin color and body type, this is the grain of truth in the lie of race. For doctors, racial categories are shorthand for guessing who your ancestors were, and whether they passed on traits from when populations were still relatively isolated. Blacks of West African descent are more likely to have sickle-cell anemia, for instance. But the sickle-cell gene shows up in Greeks as well, and many blacks of West African descent have no such sickle-cell lineage. Would anyone argue that there’s a sickle-cell “race”? If so, you might as well say there’s a heart attack race, a fast-sprinter race, an alcoholism race (see “Race Without Racism?” by David J. Rothman and Sheila M. Rothman, The New Republic, November 14, 2005).

Truth is, we’re all children of our family tree and random variation. And there’s more variation within “races” than between them. On a genetic level, you can have nothing in common with a distant relative, and far more in common with someone of another “race.” These categories don’t exist except in our minds—and in the culture.

2. Hip-hop was never one thing, and was never “pure.”

Hip-hop’s blackness is so obvious, and so overwhelming in the early years, that it’s easy to overlook the many Latino, Caribbean, Asian, and even white participants who were part of the culture from the start. Hip-hop was never pure. And it would have been a lot more boring if it were.

The very words “hip-hop” tell a version of the story. “Hip” arrived in America in the 1700s from the Wolof hepi (“to see”) or hipi (“to open one’s eyes”), according to Clarence Major’s Juba to Jive: A Dictionary of African-American Slang, and cited by John Leland in Hip: The History (HarperCollins, 2004). “So from the linguistic start,” writes Leland,

“hip is a term of enlightenment, cultivated by slaves from the West African nations of Senegal and coastal Gambia. The slaves also brought the Wolof dega (“to understand”), source of the colloquial dig, and jev (“to disparage or talk falsely”), the root of jive. Hip begins, then, as a subversive intelligence that outsiders developed under the eye of insiders. It was one of the tools Africans developed to negotiate an alien landscape, and one of the legacies they contributed to it. The feedback loop of white imitation, co-optation, and homage began immediately.”

“Hop,” meanwhile, has always been a variation of the verb “jump.” It’s also longtime slang meaning “to increase the power or energy of something,” or “to stimulate with, or as if with, a narcotic”–e.g. “hopped up on dope.”

So “hip-hop” literally means “enlightenment energized”: cool on speed, style made furious, boogaloo electrified. The term suits a culture that replaced gang warfare with competitive, omnivorous creativity. Hip-hop borrowed from everywhere, so no wonder everyone claims to be an “originator.”

According to Afrika Bambaataa, he first heard the phrase “hip-hop” at a Bronx beat party where the MC was chanting, “Hip-hop, you don’t stop/That makes your body rock.” (see Say It Loud! The Story of Rap Music by K. Maurice Jones, Millbrook Press, 1994; cited by Eileen Southern in The Music of Black Americans, Norton, 1997; Southern doesn’t identify which MC coined the name, and the question remains controversial).

Bambaataa began applying the term to the South Bronx street culture he helped create, and it caught on. By 1982, “hip-hop” referred to fashion, graffiti, breakdancing, DJ techniques, and rapping.

“We never called it hip-hop,” maintains DXT [formerly D.ST.] in Yes Yes Y’all: The Experience Music Project Oral History of Hip-Hop’s First Decade (by Jim Frick and Charlie Ahearn, Da Capo Press, 2002). “We called it b-beat music.” (“B” as in “b-boy,” “Bronx,” “beat,” or “breaking.”)

In fact, hip-hop had existed without a name for more than a decade, and far beyond the Bronx. In 1967, a black pre-teen in Philadelphia named Don Ameche ** “CORNBREAD” Stallings initiated the world’s first all-city graffiti campaign in order to woo a girl at school, writing “CORNBREAD loves Cynthia” on her desk, along her bus route, and up and down the block where she lived (see “No Rooftop Was Safe,” by Katie Haegele, Philadelphia Weekly, Oct. 24, 2001). Soon after, his clique began covering the city in aerosol art, defying gang turf along the way.

Non-gang graffiti quickly spread to Manhattan. CORNBREAD protege TOP CAT “moved to Harlem and brought with him the ‘gangster’ style of lettering,” writes Jeff Chang in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop (St. Martin’s, 2005). By 1970, a Greek-American teen calling himself “Demetrius” had begun spray-painting “TAKI 183” on ice cream trucks in Washington Heights, and soon moved on to subway cars citywide (see “‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals,” July 21, 1971, New York Times). He credited “JULIO 204” with inspiration (both writers used street numbers in their tags), but otherwise little is known about either artist.* (The 1985 Timothy Hutton film Turk 182! went so far as to give TAKI a fictional, politically rooted backstory.)

Hundreds of imitators followed, and by the mid-’70s, “the second generation of writers was more integrated than the army,” writes Chang. “Upper East Side whites apprenticed themselves to Bronx-based Blacks. Brooklyn Puerto Ricans learned from white working-class graf kings from Queens.”

The new dances were similarly national in origin. In 1970, a black student at Los Angeles Trade Technical College named Don Campbell began improvising dance moves with friends in the cafeteria during lunch, and came up with a jerky new style he called the “Campbellock,” or the “Lock.” Performing the dance in the audience at 1972’s Wattstax festival, he appeared in the following year’s concert film of the same name, and later, more influentially, on TV’s Soul Train. By the mid-’70s, Campbell’s crew, the Lockers, were making the rounds on The Tonight Show, The Carol Burnett Show, and Saturday Night Live. One televised Lockers appearance inspired Fresno’s Boogaloo Sam to form the Electric Boogaloos, and invent “the Pop” (see “Fred ‘Rerun’ Berry, R.I.P.” by Peter S. Scholtes, Complicated Fun, October 23, 2003; see “Complicated Fun, a City Pages blog).**

“B-boying” (later called “breakdancing”) was like a horizontal, East Coast parallel to Locking and Popping. It took on the fierceness of the New York youth practicing it, many of whom belonged to gangs such as the Black Spades (black), or the Savage Skulls and Savage Nomads (Puerto Rican). But the gang culture had begun to give way to party crews like that of Jamaican-born Clive “Kool Hercules” Campbell (no relation), who pioneered an American variation on the Jamaican sound system. When Bambaataa, a former Black Spade, began actively recruiting Skulls and Nomads into his Zulu Nation party crew, he effectively did what no community organizer had bothered to try: He desegregated the Bronx River Houses. (As a DJ, Bam was similarly open to every genre–and still is.)

By 1976, Latinos were flowing into what had been a mostly black milieu, and revived the b-boy dances that blacks had begun to abandon. “See, the jams back then were still close to 90 percent African-American, as were most of the earliest b-boys,” says Trac 2, quoted by Cristina Veran and cited by Chang. “They were like, ‘Yo, breaking is played out’ whenever the Hispanics would do it.”

But Latinos gave breakdancing new life, and just when rap music was starting. Latinos took part in the music, too: The DJ behind pioneering rapper DJ Hollywood was a young Latino named June Bug. Other barrier-breakers followed.

When hip-hop moved downtown in 1980, gaining a new audience of punks and art radicals, some of these fans joined the ranks of producers, managers, and label owners who helped launch the music into mainstream America. “I’d argue that without white entrepreneurial involvement hip-hop culture wouldn’t have survived its first half decade on vinyl,” writes Nelson George in Hip Hop America (Viking, 1998). Contrary to myth, George adds, whites bought the records, too.

Of course, some claim this was the end of hip-hop, which brings us to…

3. Gangster rap is not a white conspiracy against blacks.

Nobody actually thinks this, but some talk as if they do. The suspicion underlies legitimate unease about a subculture’s passing into the magnifying realm of commerce. When the Memphis rap crew Three 6 Mafia recently took the Academy Award for “It’s Hard Out There For a Pimp,” performing the song on Oscar night, some critics even used the metaphor of minstrelsy–as if white America had made puppets of these black artists.

The myth of white control usually ignores gangster rap before it became massively popular. So we can skip Philadelphia’s Jesse “Schoolly D” Weaver (the Parkside Killers member who recorded a cold-blooded single in 1985, “P.S.K. – What Does It Mean?,” as an ode to his gang). Skip Ice-T, Boogie Down Productions, and even the first album by N.W.A. (“Niggas with Attitude”–hard to remember the shock of that name now). Instead, start with Ice Cube’s departure from N.W.A., and the group’s subsequent album without him.

The Cube-free N.W.A. was the first hardcore rap record to hit No. 1. The same year, Cube’s “No Vaseline” needled his old crew-mates about their manager, Jerry Heller: “Get rid of that devil real simple, put a bullet in his temple/’Cause you can’t be the Nigga 4 Life crew/With a white Jew telling you what to do.” By the time N.W.A.’s Dr. Dre released his blockbuster followup, The Chronic, other ’80s heads seemed ready to believe that the new mass audience was a corporate brainchild.

“The record industry created gangster rap,” said Chicago MC/graffiti writer Super LP Raven in the seminal 1994 book by graffiti artist William “UPSKI” Wimsatt, Bomb the Suburbs (The Subway and Elevated Press). B-boy Reginald Jolley expanded on the point elsewhere in the book: “The first formula for commercial rap was smiling and acting innocent–Young MC, Hammer, etc. Now the formula is taking the happy beats–Dre’s production which is not hip-hop at all–and to put it with the savage lyrics.”

But Jolley’s objection was social, not just aesthetic. “Once gangsta rap came out, it made all the gangbangers like rap,” he said. “They used to dis us. They used to call it breakdancing music. Gangsta rap crossed the thugs into it.”

In truth, it wasn’t the expanded white audience for rap that bothered many old-schoolers, but the expanded black one. “Hiphop as extremist and repugnant as N.W.A.’s or 50 [Cent]’s was a benevolent trickster god’s way of pinching us to make sure we were still awake,” wrote Greg Tate in the Village Voice last year. “Now it’s one more trick of the devil, his way of keeping us compliant, complacent, and comatose. If the creators of The Matrix had read Ralph Ellison they wouldn’t have romanticized Black people as too worldly to fall for a virtual reality” (see “Married to the Hook: The corporations murdered hiphop and all I got was this lousy G-Unit throwback jersey” by Greg Tate, Village Voice, March 11, 2005).

The fact is that gangs have always shaped hip-hop. But as gangs changed in the ’80s, hip-hop changed with them. By the mid-’90s, after crack cocaine’s sweep through the inner cities, many urban fans in the Deep South, West, and Midwest were hungry for “reality”–however virtual.

A new audience made folk heroes not only of Biggie Smalls and Tupac, but of otherwise widely obscure fallen “soldiers” such as Seagram Miller in Oakland (on Houston’s Rap-A-Lot label, operated by Scarface) and Soulja Slim in New Orleans (on Louisiana’s No Limit, operated by Master P). “Only Juvenile and Mystikal were in the same league, and neither owned the streets like Slim,” writes Nik Cohn in Life & Death & New Orleans Rap (Knopf, 2005). “His was the voice of black New Orleans, in all its ugliness and beauty, its senseless slaughter, its moments of battered grace. He personified the split that lay at the city’s heart–fierce joy in being alive, compulsive embrace of death.”

Today, when a hip-hop fan dismisses gangsta as “inauthentic,” ask him if he isn’t just inventing an excuse to avoid venturing beyond his comfort zone and into the kinds of neighborhoods where hip-hop was invented in the first place. Ask him if, by identifying the mass (white) audience of the music as the problem, he isn’t using someone else’s supposed racism to let himself off the hook for his own fear.

4. Hip-hop can’t change the world.

But you can. And hip-hop can change you.

When people talk about “hip-hop activists,” they usually mean activists who like hip-hop. But the important half of that equation is the political one. Simply put, Public Enemy does music. The Black Panthers did breakfast programs. Spike Lee does films. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) did voter registration. Kanye West does art. ACORN does politics. Not that hip-hoppers aren’t good activists: Afrika Bambaataa was a community organizer who threw parties. But he did the work, not hip-hop. William “UPSKI” Wimsatt was a youth advocate who founded the League of Pissed-Off Voters. He did the work, not hip-hop.

How do you change the world? You organize.

And if you wait for hip-hop or anything else to inspire you, you’re putting the cart before the horse.

Waiting for hip-hop to change the world is a little like waiting for “leaders” to change the world. Stop waiting. Any good changes you can name in the culture, in the economy, or in the body politic came about as a result of ordinary people, not politicians. Today we have better coffee and food than we did a generation ago, not because of any law passed by Congress, but thanks to “hippies, organic farmers, farmers’ markets and community supported agricultural networks” (see Dime’s Worth of Difference: Beyond the Lesser of Two Evils by Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair, AK Press, 2004).

Today music is funkier because of hip-hop. Americans are more honest about race because of hip-hop. Fill in your own good influences here. But these are also a delayed legacy of ’60s and ’70s activism, of people’s movements that won concrete goals, pressured new legislation, shook up the economic establishment. The general shift between the years of Malcolm X the man (in 1964) and Malcolm X the movie (in 1993) was from voter registration to electoral campaigns, grassroots politics to culture and commerce, substantial revolution to the symbolic kind.

“[Spike] Lee’s strongest images suggest the immutability of white racism… rather than the possibility of overcoming it,” writes historian Clayborne Carson of Malcolm X in Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies (Owl, 1996). “His film’s Malcolm ends his life resigned to his fate rather than displaying confidence in his hard-won political understanding. The film’s Malcolm becomes, like the filmmaker himself, a social critic rather than a political insurgent.”

Rap’s “conscious” era of political theater in the late-’80s echoed an earlier era of actual politics, but hit the universities harder than the streets. Out on the corners, the forces changing society from the pavement up were gangs, and the sale and distribution of crack cocaine. If ’60s rebels created Chuck D’s worldview, ’80s crack birthed today’s drug rapper.

“Even more than viciousness and misogyny,” writes Nik Cohn,

“what made gangsta so troubling was its absolute absence of hope. Beneath the cartoon overkill, it spoke of a fundamental shift in how young black men saw the world. Years earlier, in the South Bronx and Bed-Stuy and Harlem, I’d listened while B-boys talked. Many were angry and frustrated, none defeated. Even on the meanest streets, there was a feeling of possibilities. The Civil Rights years were still the recent past; progress was, if not guaranteed, at least in the cards. There were things worth believing in and fighting for.

“Already that times seemed long lost. When I listened to street kids, I heard paralysis; a dull weight of futility. If I asked how they saw their futures, they looked at me as if I was babbling. What futures?…

“Gangsta spoke to a death of the heart. At least in the beginning, it wasn’t a music for African-Americans–the black people who had managed to cross over into the mainstream, with their college degrees and suburban homes, their standarized American speech–but for Niggaz. The permanently jobless, the semiliterate, the fucked, who grew up without fathers, or with fathers in jail, or, perhaps most pernicious, with father stuck in menial jobs, shit work for shit wages. If they tried to study in school, they were called faggots. If they worked, they got minimum wage, if that. And every day they saw drug lords cruise by in luxury cars, bodyguards in tow, fine women all over them.”

5. The hip-hop generation has plenty of leaders. Maybe what we need is more organizers.

We have leaders in business, music, church, and elected office. What we lack is a collective memory of what political organization means. “The basic difference between the leader and the organizer,” wrote Saul D. Alinsky in 1972, is that the leader “wants power himself. The organizer finds his goal in creation of power for others to use” (Rules For Radicals, Vintage Books).

“Effective organizing in 1960s Mississippi meant an organizer had to utilize the everyday issue of the community,” writes Robert P. Moses, a former SNCC activist who helped black sharecroppers destroy segregation in the ’60s. “Small meetings and workshops became the spaces within the Black community where people could stand up and speak, or in groups outline their concerns. In them, folks were feeling themselves out, learning how to use words to articulate what they wanted and needed. In these meetings, they were taking the first step toward gaining control over their lives… This important dimension of the movement has been almost completely lost in the imagery of… dynamic individual leaders” (see Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project, Beacon Press, 2001).

The issues addressed by these men and women are still with us–collapsing schools, youth violence, war, poverty, racist oppression, and the abandonment of America’s most vulnerable (for example, in Soulja Slim’s New Orleans). Hip-hop won’t defeat these evils any more than gospel music defeated Jim Crow. But it can provide a place to talk about them. You provide the rest.

________________________________________________________

*In 2000, TAKI 183 resurfaced with a phone call to the New York Times. “The name-signer who launched a thousand felt-tipped pens would say only that his real first name is Demetrius, that he lives in ‘lower Westchester’ and that he works with cars–again, no details,” wrote James Barron, quoting TAKI: “‘I’m a family man; I’m a mainstream guy… Sometimes I see a wall and say, it would be nice there. I guess I’m a dangerous guy to carry around a marker, still. But that’s something you do when you’re 16. It’s not something you make a career out of.'” (See “Off the Train, Onto the Block; Auction House to Put Vintage Graffiti on Sale” by James Barron, New York Times, June 10, 2000.) Inexplicably, TAKI’s Wikipedia entry states: “his tag was short for Panayiotakis, the diminutive of Panayiotis” (see the Wikipedia entry for TAKI). So is there a Demetrius Panayiotis out there somewhere with an internet connection?

JULIO 204 (who was reportedly Puerto Rican and a member of the Savage Skulls) might also be around. At a 2005 New York graffiti celebration in Chelsea, an aerosol artist painting “COPE” was asked by a photographer to give his real name. “Julio 204,” was the grumbled response, as reported by Anthony Ramirez. The graf writer turned back to his work: “‘That guy wanted me to be a model,” he said to no one in particular. ”I ain’t no poser” (see “That Sweet Smell of Youth, Hissing From a Spray Can” by Anthony Ramirez, New York Times, August 25, 2005).

**Every member of the Lockers turned out to be influential in his or her own way: Group choreographer Toni Basil championed L.A. punk and was a one-hit wonder with “Mickey”; Adolfo “Shabadoo” [or “Shabba Doo”] Quinones became Ozone in the epochal hip-hop films “Breakin’” and “Breakin’ 2 – Electric Boogaloo”; Deney Terrio hosted and choreographed TV’s original “Dance Fever”, and taught John Travolta his moves in “Saturday Night Fever”; and Fred “Rerun” Berry brought the Lockers’ style to a wider audience on TV’s “What’s Happening”.

** Brian Campbell, of the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program emailed us the following correction on 4/23/13, contesting Toki Wright’s observation about Cornbread, saying: “Cornbread’s given name is Daryl McCray. Don Ameche Stallings is an entirely different person who wrote under the moniker PRINK. He joined the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network in 1985, which later became the Mural Arts Program.” [RETURN]