Held in a Corner: Mater(iality) and Mater(nality) in Liz Larner’s Corner Pieces

An experiential counter-reading of three sculptures by Liz Larner—on drywall as body, how support gets overlooked, the tension between agency and resignation, and what has become of the promise of feminism

Note: This piece discusses intimate partner violence in the eighth paragraph.

The temporary wall has been up a long time, so long it may seem permanent to most. I remember as a child always seeing Franz Marc’s The Large Blue Horses centered within the long white expanse of this Walker gallery wall. I loved those blue horses and that the painting was always there, though different artworks from the collection would hang around it. I remember the first time I walked into this first gallery and Marc’s Blue Horses were gone. I was shocked and a little disoriented, and surprisingly disappointed. By this time, I was an art history major in college and already focusing on more cutting-edge contemporary art.

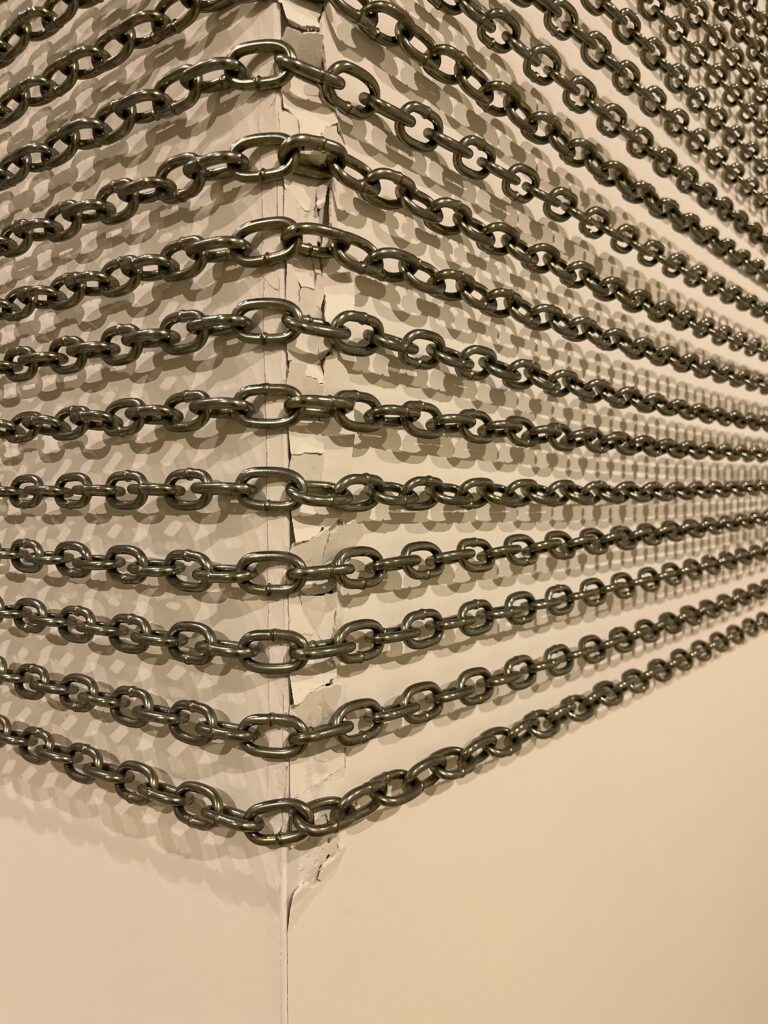

Currently, one corner of this large, seemingly empty white wall is bound onto a new, smaller temporary wall. This added wall creates the necessary structure to hold Wrapped Corner by Liz Larner. Over 20 metal chains straddle the edge of the two walls, and connect to vertical bars that pull the chains, making them taut and straight. In fact, the turnscrews have been turned so tight that the chains dig into the corner’s perfect edge. The plaster cracks and breaks under the force of the chains. A pressure unable to be withstood by something so solid, plain, and unremarkable in a gallery: a wall. Typically overlooked, it will continue to stand despite its edge crumbling.

I stood there staring at the small cracks and dents in the plaster, mesmerized, while the artist spoke about balance, about refusing gravity, perhaps about form. I stopped listening because I felt this unbearable, unexpected pressure in my chest, felt the constraint of the chains on my body and psyche. Felt their cruelty. Larner spoke about the chains, but I had far more interest in the wall. I felt more and more certain that this slightly crumbling wall corner piece was in fact about me, my life circumstances, meted out to so many women. Covert, without any mark-making, the sculpture is nothing without the wall. Both the artwork’s support structure and its captive. This chain-bound corner has everything to do with women, patriarchy, and the body. Women limited and held back by so much: bound by obligation and marriage and children, inequality in so many career tracks and salaries, including art and academia. Granted, this gets personal to my own story—not necessarily lining up with all intersections of identification as female, but rather pinpointing the experience of women who bear children, and applicable to intimate partner relationships that pivot around childbirth and rearing. I left that corner, still aching, strangely wanting to stay longer to see how the wall fared. The crushing of matter, of mater(ial), of mater(nal) solidity bending to anger and to pressure…to do so much childcare, housework, thinking, driving, mending, placating, just to get time to work. Will the turnscrews be tightened? How much pressure can the wall take?

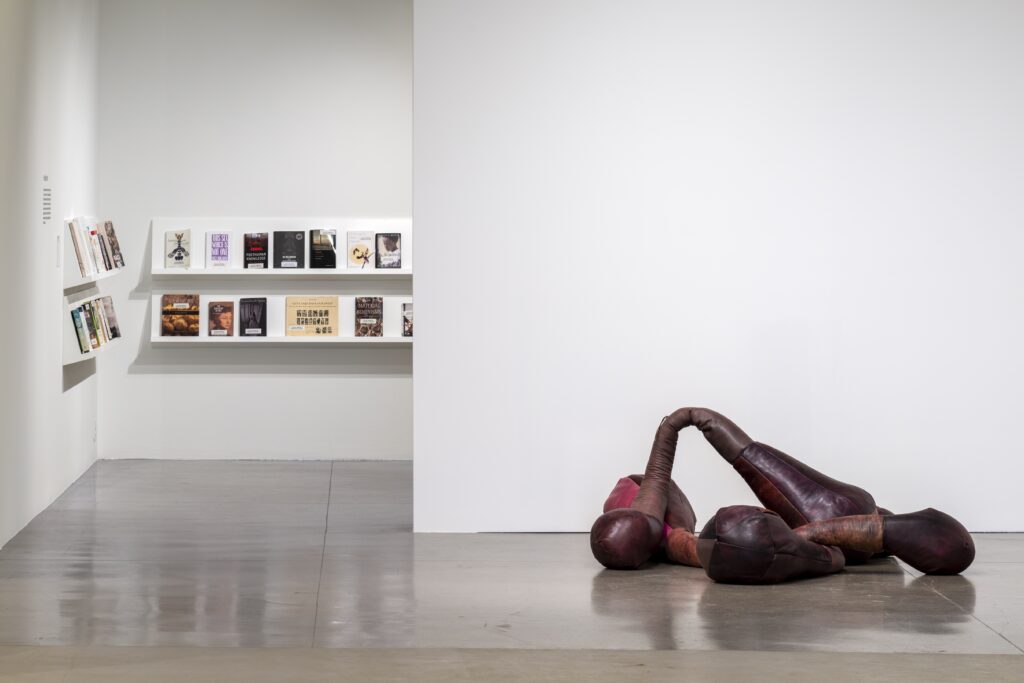

Due to the strange kinship I felt with the wall, I continued on with the group from the press preview event for Don’t put it back like it was, and walked to the edge of the added temporary wall. I needed to know what was behind Wrapped Corner, if there was evidence of its anterior. What were the consequences of such pressure and constraint? “Oh,” I thought when I saw Too the Wall drooping on the opposite side: “There it is, the weight of the mother’s body.” At first, it seemed like a spider’s web spun in the recesses of a corner due to its shadows on the wall. Looking closer, I see it is more like a cradle for the womb at full gestation, caught in the hidden container of the corner. The moment of expectation, just before birth.

Too the Wall sags in the corner directly behind Wrapped Corner. Slim, carefully measured silver strips, linked together in rows, cascade one beneath the other from smallest to largest. Stitched into the central bowl of the linked silver strips are rectangular, beige leather patches that increase in size as the hanging strips get larger and descend down from the corner of the wall. There is a patience, and a waiting so long that the form melds into its container, the two-wall enclosure. The only pressure here is the weight of gravity, nature’s inevitability taking full force. Where Wrapped Corner defeats gravity, Too the Wall sees no point in resisting nature. Instead, this piece gives into the corner, resigned but beautiful. The work feels both weightless and very heavy, tender and transgressive. And it reminds me of how hard it is sometimes to be a woman, the bearing-down weight of misogyny and the weightlessness of having little to no influence. The perfect alignment of the metal lines reminds me of how perfectly my body seemed ready and able to gestate a baby, waiting until my mid-30s, effortlessly getting pregnant into my 40s. I had felt so pushed aside as a new mother, felt lodged in that corner, that my career was all effort, constantly pushed to the wall—even though I made it through my doctorate, teaching and publishing. While this other thing, found in the body I had kind of ignored—having babies—felt like happenstance, a part of living. That’s what this piece conjured up for me now, my body responding so strongly to it, exacerbated perhaps by the need to check behind me to see if my youngest, 11 years old now, was walking with me and with the group. She tagged along with me for the gallery walk-through, out for an art day with her mom.

I presumed the artist prescribed none of this to her work—although at the same time, I could tell by her intentional use of the walls in this gallery that I was within reason to empathize with the wall. Also, I still couldn’t seem to listen to what the artist was saying. I went to this press preview event without reading any material and oddly not knowing about Liz Larner. When I saw the press release, I knew I would love this show because of my research on women sculptors. I wrote my doctorate on Irish women’s sculpture from the 80s and 90s. I could tell from these first few works in the gallery walk-through that this artist should have had a bigger impact, been more prominent in the range of art history textbooks I had taught from for years. Then, I turned around to look at the corner on the opposite side of the gallery, only to see a menacing piece of industrial equipment, and felt further dread about the fate of these walls. I bent down and whispered to my child, “I think you should grab your book and go read in the lobby.”

Larner says in Artforum, “Hey, walls are spaces too.”1 And in continuation of my wall identification, my mind jumps to claim agency for more than just walls. I mean, “Hey, women are people too,” or “Hey, women are artists too.” Because all three statements are of course, redundant—we all know this! But the obvious may need to be pointed out during times like these. I realize that this may be a strange way to look at the situations that Larner creates for walls and their corners. But identifying the walls as female, or personifying them as having an anamorphic quality that represents women in the artworld—as often ignored, as only good for hanging around to hold the art by real artists—the walls might then speak volumes. There is a sense that these walls are punished for even attempting to speak. That things are done to them, and violence is enacted to maintain their passivity, is most stunningly performed in Corner Basher.

Upon first glance, Corner Basher is awkward and funny, a piece of basic mechanics that takes a ball and chain adhered to the top of a tall metal pole, and as it turns around faster and faster, the ball hits the walls. There is an equally industrial-looking dial beside the sculpture that viewers use to power up the basher. It is loud and boisterous in its deconstruction of the wall—not an all-out destruction like a real wrecking ball. Considering that I am still reeling from my initial encounter with Wrapped Corner with its pressure so intense, I can still feel the chains digging into the wall. Now, with Corner Basher, it feels dangerous to continue this empathetic correlation with the walls that lie dormant. I wish to protect the walls for doing their job of supporting the whole structure, upholding their responsibilities, doing what society expects of them or even needs from them, mercilessly stuck and taken for granted. I am scared to take this to its next obvious word play and move from “wall basher” to “wife basher” or “wife beater.” So then here it is, this clunky, outdated ball and chain—the common slang for marriage—it just rips into the wall with the power that gravity and mechanics gives it, saying that you need to stay in your (domestic) place: take care of the kids, do the laundry, feed everyone, do your job or you will get hurt.2 The act of scraping away at a surface, wearing it down, acts like harassment, for “to harass” literally means “to scrape.” This wearing down feels like sustained, habitual violence. The violence laced within these corner pieces can be pulled apart in a myriad of ways.

I know that the prevailing reading of Liz Larner’s work puts the power of Corner Basher in the hands of the viewer, and the switch on the wall into the hands of women, especially in 1988 when she made it. This machine aimed to break down barriers and change the structure through deconstruction of the institution that holds art, that collects art mostly by men, that makes male artists vastly out-earn women artists.3 As Connie Butler states in the catalogue, the work is “a symbolic dismantling of norms” and “a celebration of force” that is “both persistent and joyful in its desire to take down the wall as we know it.”4 Larner unleashed the macho machinery seen in the work of male sculptors of that era in order to do what women needed to do—to cause a ruckus, push boundaries of materials and forms, and break down the walls that had kept them out of museums for centuries. Even Butler acknowledges that these walls “show scars,” and references that Larner intended Corner Basher to be paradoxical and ambiguous.5

I keep thinking of the era of when Larner made these corner pieces, 1988-1991, the early years of women’s studies departments. I remember seeing Jenny Holzer’s Venice Biennale show in these same galleries, when she became the first woman to represent the U.S. It was 30 years ago, late 1990, and wow, how I thought I would do it all differently than my stay-at-home mother of seven, an artist finding tiny crevices of time to paint. This was the same year I wrote my undergraduate art history thesis on Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, whose work I had seen for the first time in 1990 in a Chicago gallery. Uncannily perhaps, the work of Holzer’s that continues to affect me the most from her Walker show was about the maternal. Encased in Holzer’s signature style of cascading LED lights, reflected back from the white Walker stone floors, was a mother’s voice yelling that if anyone so much as laid a hand on her child! I didn’t personally yet know this maternal power that would cry out from the belly at the thought of someone harming my own. But I still feel the rage and unstoppable force pulsing out of the work’s blinking lights. As that primal power surged within this female protagonist via the factual transmission of a marquee sign, it left some sort of premonitionary mark on me, because it is the only part of this exhibition that has repeatedly come to mind over the years since. It strikes me now as remarkable that Holzer uses the female voice in her work of that era as either vulnerable or maternally powerful: “Men don’t protect you anymore” (in Survival Series) or “A man can’t know what it’s like to be a mother” (from Truisms.) Partly, I feel misled: the superhero physical quality that the mother possesses in Holzer’s work has revealed to me over time that it is a socially maligned power, holding back mothers from having power in any real sociopolitical or economic way.

Misogyny is meted out in Larner’s pieces via the grip of constraint upon the body and the psychic pressure of still-too-tight chains. With Larner’s method of taking the walls of the gallery space seriously, she creates space for critical conversations about the bounds of the maternal body. The violence is dust on the floor of Corner Basher. “We will leave the pieces of the wall where they land. And a lot of it is just dust,” Larner says.6 But this dust is also everything, all that we have to show for the hurt and subterfuge that is invisible. It shows the remains of a life caught up in bodily expectations and promised liberation, showing how the artwork binds us to the structures that seek to hold us down.

Maggie Nelson’s latest account of feminism and sexuality in On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (included in the reading room space nestled toward the end of the exhibition) concludes on a feeling of both/and: “We cease measuring the status of our liberation against the ideal of an unfettered, static, happy sexuality, and commit instead to the ride, knowing that certain unfreedoms and suffering will always be part of it, even as we work to diminish their prevalence and force.”7 Violence is held, complicatedly enduring in its range of implications in Corner Basher. Its violence is conciliatory and antagonistic toward sexism and misogyny, living within its bounds while fighting against it. It is hard to realize a life without living in the balance of the two extremes rocking our world right now, in the wild pendulum swing found in Larner’s ball and chain.

I hope that it will someday be okay, and that the social, political, and economic quagmire of centuries of sexism will be disturbed and shaken up by future generations. The youth of today just don’t see gender as fixed. My 11-year-old, the one tagging along, has told me she sees herself as genderfluid. She (the pronoun she uses) says some days she feels like a boy, some days like a girl, and somedays a bit of both. She also has chosen a new androgynous name and asked to start last school year as River. River’s gender doesn’t always present itself in how she chooses clothes for the day—she can be a boy and wear a dress some days. My maternal power (à la Holzer) embraces this child and all her life and its possibilities, protecting her sense of self where I can. And now, these children are alongside us, coming up close behind to take up the torch and see us through to the other side.

Here it is, then, for you to see: the amazing flipside of mothering, its privileges and lifegiving properties. It ensures that the life-swerving reorientations and career sacrifices that society can still demand of mothers feel entirely worth it.

Liz Larner: Don’t put it back like it was is on view at the Walker Art Center through September 4, 2022. >> more information