He Qi: Two Levels of Amazement

Dean Seal attended a show of Chinese religious paintings at the Premier Gallery, 141 South 11th Street, in Minneapolis, and was impressed and touched by the work.

The Premier Gallery in Downtown Minneapolis is hosting an innovative cross-cultural artist from Nanjing from now until the end of January. Whatever it is you do, whatever you are interested in, let me say this about that: Must See. Qi (pronounced ho chi, not Quie) does two absolutely remarkable things. I’ll tell you about them one at a time.

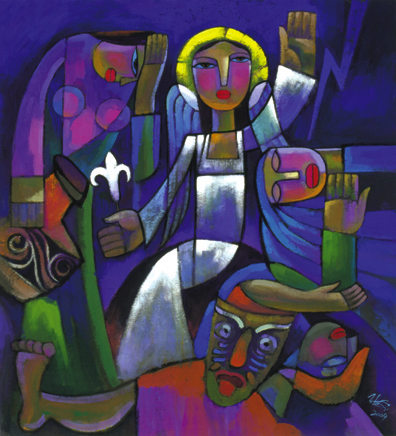

He Qi is a professor a Nanjing Union Theological Seminary and is categorized as a contemporary Christian artist, a rare commodity to come out of the People’s Republic of China. The paintings in this exhibit are of biblical motifs, both New Testament and the Hebrew Bible, and they are wonderful compositions that seamlessly combine many different styles. In a nativity scene with the Magi, he has traditional folk elements of peasant portraiture combined with modern depictions of the Wise Men, each in a style accurate to their background from Asia, Europe, and Africa, as the tradition tells us. Yet the gift that is centered in the picture is a blue-and-white vase from the Chinese tradition that is rendered so accurately it might have been cut out and pasted into place. In a quasi-abstract take on the story, this telling detail is the only thing painted realistically, and he chose a work of art.

He uses bright jeweled colors and soft pastoral organic backgrounds for his gouaches. His depiction of Mary as a Chinese woman, or the finding of the foundling Moses by a Chinese princess, is a conscious effort to make the Christian story familiar, more universal. This is as it has always been: Jesus is the Greek name given Yeshua by the Greeks; a blue-eyed Jesus has been featured for many years on Scandinavian calendars; African nativities have African shepherds gathered around an African mother and child. To take this action is not new, but Qi pulls it off in style.

Qi was getting ready for his reception when I asked him about the difficulties of being a Christian in a communist country. “During the Cultural Revolution, all the foreign missionaries were sent out. I was put out in the country, but I couldn’t do the hard work. They needed people to make statues and paintings of Mao, to worship him. I thought, that’s a good job for me. So I got that job for my area. At night, I would paint soft pictures of the Madonna.

“I felt our people had the struggle-spirit too much. Every day, struggle. I wanted to create peaceful scenes. We need to hear the peaceful voice of heaven.”

His studies of medieval paintings in Europe use colors that seem as bright as stained glass. He also draws his palette from minority folk art traditions. Combining these with modern design, he renders work that is fully Chinese and fully Christian, being of one substance, as it were.

The paintings are strongly evocative of the story portrayed. “Out of the Garden” has the angel casting Adam and Eve from their secluded paradise, which is surrounded by a small wooden fence and a tiny gate. “Abraham and the Angels” has a skeptical Sarah in the back, a welcoming and hospitable Abraham as the proud householder, and three faceless, bi-gendered angelic guests, mysterious and yet casting a beautiful shimmer through the room. “Elijah and the Raven” is a countryside portrait of the prophet in hiding, being brought food by God’s raven. Elijah looks at peace, in comfort, amazed and grateful by this inexplicable act of generosity from the God he is serving. The colors are more muted here and convey a more realistic tone, the texture of the landscape.

Oh, and the second amazing thing? There’s another dozen pieces that are made from silk, woven into tapestry. This is the part that has to be seen to be believed. It’s one thing to experience an artist doing moving, profound work; it’s quite another when that same level of excellence is run through a process one has never encountered before, never even heard of. Each silk strand is dyed by artists who have been building the skills of the craft for many thousands of years (the country’s name was originally “Silk”) and under the watchful eye of He Qi, they take about a month weaving these pieces. The light changes and jumps as you move past each piece; some landscape backgrounds are done in several shades of green, and as you walk by they shift in emphasis; the magnificent jewel tones and the classic modern compositions stay true to the artist’s forms in his paintings. There is no way to do this work justice in words; go see. It’s a brand new thing to me.

The story of Ruth and Naomi is done in a swirling abstract of rounding forms, feminine yet undefined as separate people, a merger of two souls. The Song of Solomon has a collection of motifs drawn from the book of erotic poetry that pairs the gorgeous half-naked lovers with the metaphors they use to describe each other in lingering, hot-breathed longing. “Sleeping Elijah” is a symphony of green silk, a cascade of wandering colors that glitter and murmur with each passing. The effect is stunning.

Let’s hope for a long successful run and a prompt return to some of our higher education institutions in the near future.