Everything and More

Travel writer Frank Bures, with a perceptive essay on Argentine artist Guillermo Kuitca's evocative, map-filled paintings and drawings, on view in a sprawling retrospective show, aptly titled "Everything," at the Walker Art Center through September 19.

WHEN I GOT HOME FROM THE NEW GUILLERMO KUITCA SHOW at the Walker, I sat down at my desk, took out a piece of paper, and sketched the floor plan of our home. I had seen it before: the stairs, the small closets, the tiny room where I work. That room is an office now, but many years ago it was built as a kitchen in an upstairs apartment.

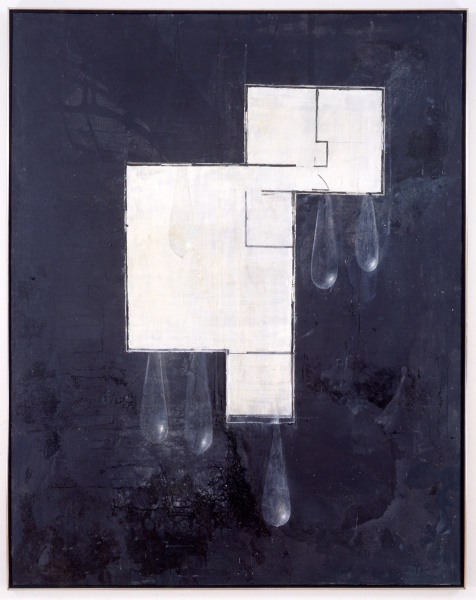

As I thought back to a painting I’d noticed in Kuitca’s show, though, the floor plan of our home looked a little different. The lines seemed to me now like the skeleton of something almost alive, and we were the meat on its bones. That painting, House Plan with Tear Drops, showed a simple floor plan like the one in front of me, only his had large tears falling out from the edges.

I know, the image sounds almost maudlin, but the painting is a dark and beautiful work; it makes me think about the lives lived in that house, and the lives that have been in mine — and how we, too, would someday be invisible to the people who eat, sleep, and cry here. These future residents will have no images of us cooking our food, arguing, laughing, screaming, and making love in this place. To them, the walls will be blank things on which they can write anything they want.

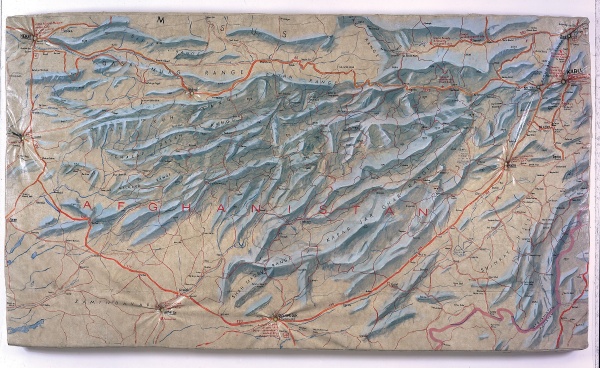

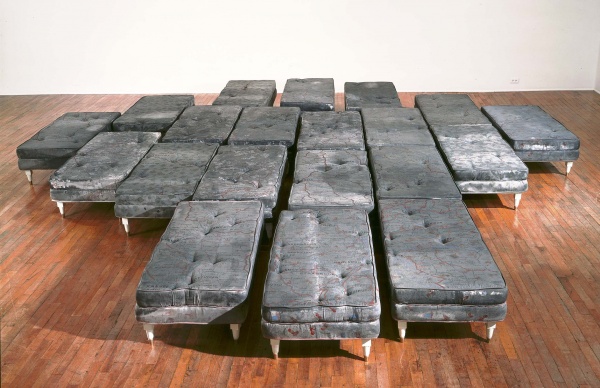

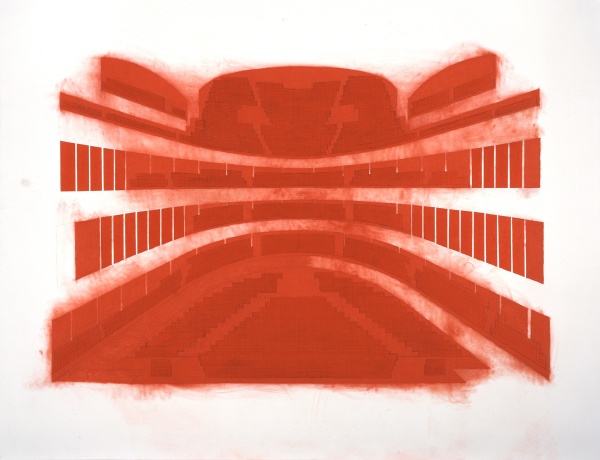

House Plan with Tear Drops is just one of many paintings in the exhibition, Guillermo Kuitca: Everything, that centers on certain commonplace schemata. There are sketches of prisons and theaters, and of other houses and buildings. The images are beautiful in themselves, but I have the sense that these are merely starting points, places where Kuitca wants the mind to begin building something else. One room in the exhibit is filled with mattresses which have maps painted on them. The incongruity of the coldness of cartography laid across the human warmth of a bed reflects a tension between the sterile topography of life and the intimacy found in our actual lives. These poles seem to be at work throughout the exhibition, and maybe throughout all his work.

Maps are a major theme in Everything: they are everywhere in his work, torn up, distorted, and pieced together. They hold an appeal for Kuitca, perhaps for their attempt to impose a kind of order on the chaos — it’s as if we sketch these lines across the land to control it, even when we know that we really cannot. It was in 1987 that Kuitca first fell in love with maps, he says. He was in Prague, looking through a guidebook when for some reason, the map of the city struck him, and he tore it out.

Only later did he realize that this moment would define his future as an artist, or that the map would prove to be a key piece of a puzzle he had been trying to put together. And only later did the sequence of connections become clear to him: how he had gone from painting beds, to painting house plans, to painting maps, as if he were tracing the lines that frame our lives, revealing the scaffolding upon which we build our worlds, digging out the bones of life.

______________________________________________________

Kuitca went from painting beds, to painting house plans, to painting maps, as if he were tracing the lines that frame our lives, revealing the scaffolding upon which we build our worlds, digging out the bones of life.

______________________________________________________

Maybe that’s what gives Kuitca’s work its unusual energy: an emotional gestalt we bring to the empty spaces he creates. In the show, there is a painting called Terminal, which is nothing but an empty baggage claim belt. There is another, related piece called Unclaimed Luggage, which shows a series of variously-shaped baggage claim conveyor belts, seen from above, each with a single lost bag on it, going around and around and around, unclaimed.

At the end of the press tour I was on, Kuitca actually stopped in and offered to answer some questions. He seemed shy, like a schoolboy being called on, as if he were almost embarrassed to be there. He looked at the floor, while doing his best to answer our questions about his intentions, his choices, what he was trying to do. His voice was very soft.

Then one of our group asked him to describe a “satisfying reaction” he’d seen someone have to one of his paintings. The question seem to catch Kuitca off-guard. After all, it’s really almost the same question as: “What are you trying to do as an artist?” or, “What is the point of art?”

He fumbled around a bit, then offered this: Whatever happens between a person and one of his paintings, he said, is between the two of them; he doesn’t want to know the details. Kuitca said that the highest praise, for him, is when someone has told him they had “a moment” with one of his paintings. He said he didn’t need to know what that moment was.

Eventually, we ran out of questions, and people in the tour wandered off on their own. I turned and walked down the room to the massive work from which the exhibit takes its name: Everything. The piece is ten feet tall and 22 feet wide, made of four panels that together look as if they must have taken a lifetime to paint.

From a distance, Everything looks like something dense and biological and alive. It is beautiful to see. As I got closer, though, lines and forms emerged; I could see the tiny fragments of worn maps — roads, cities, open spaces. Suddenly, I could imagine all the tiny people living among those fragments, along those roads, in houses and beds too small to see or imagine. I don’t know why, but this realization came to me all at once. My arm was lined with goose bumps. I felt a catch in my throat and noticed the hint of a tear in my eye.

I stepped back, and the painting took its shape again; I could see how he had woven the fragments together. Then, I turned to leave the museum. On my way out, I passed Kuitca. He was being interviewed by a TV reporter, and I thought for a minute of stopping to tell him what a powerful painting I thought it was, how much it affected me. Then I remembered what he said; so, instead I kept walking and, for the time being, decided to keep all that between Everything and me.

______________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details:

Guillermo Kuitca: Everything – Paintings and Works on Paper, 1980 – 2008 will be on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through September 19.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Frank Bures is a writer based in Minneapolis. More at frankbures.com.