Eric-Paul Riege: (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́)

Weaving as dance, as listening, as container for memory and vehicle for rebirth

At the opening of Diné artist Eric-Paul Riege’s solo exhibition, the afternoon light streamed in the western-facing window at Bockley Gallery, hitting one of six hanging fiber works, creating dancing shadows on the floor.

“I consider everything I do living and activated, and one way that happens is through gravity,” says Riege, a member of the Charcoal Streaked Division of Tachii’nii. “Even the rotation of the Earth—being able to move them or sway them. When that door opens, and there’s a breeze that walks in, they’re all activated by the breeze.”

The series of soft sculptures are made of a combination of muslin, mixed fabrics, polyester fill, faux fur, and synthetic and real hair. Four of the pieces also have sheep wool and yarn, as well as metal cones used to make jingle dance dresses.

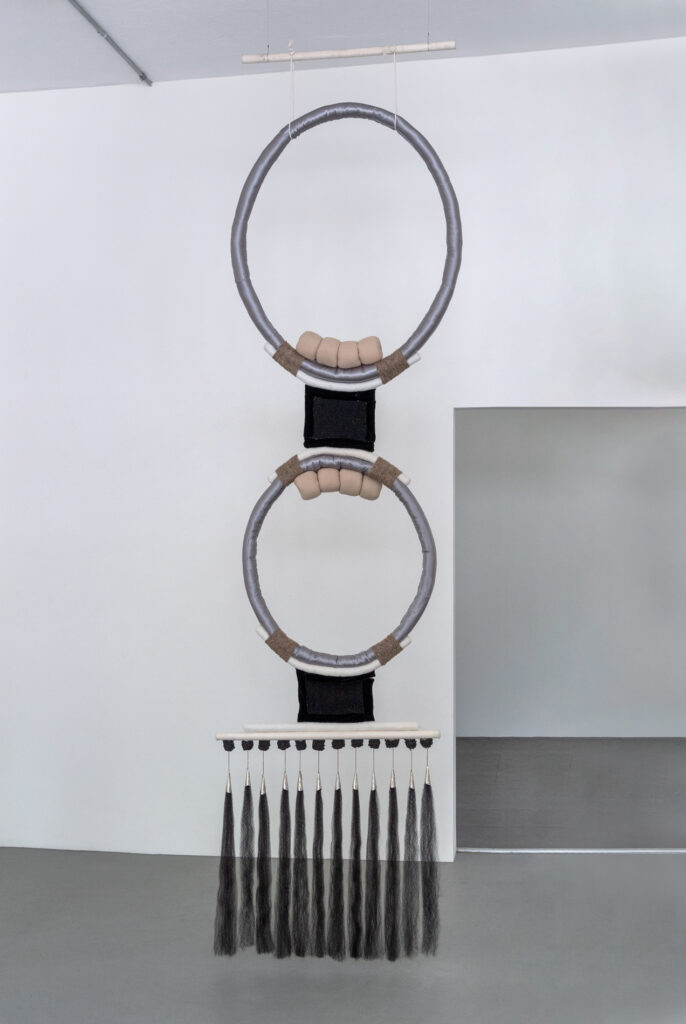

The title of the series, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh, translates roughly to “earring for the big god.” The mobile-like pieces resemble dangling jewelry. One pair of earrings are a muted jade color, with cushiony pillows making up the “beads.” At the bottom of the loop are four creature-looking adornments, with loose hair hanging toward the ground.

Another pair of sculpture jewelry features thick columns of wrapped wool, separated by cushiony fur beads. A third set looks like metal hoops from a distance, but those too are soft and moveable, with the suggestion of knuckles grasping onto the hoops.

Eric-Paul Riege, (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́), 2021. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1], 2020. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1], 2020. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

They are majestic but also intimate. The title of the series references Ye’iitsoh, giant god-monsters in Diné myth, as if these creatures were wearing enormous jewelry. Riege says that jewelry is an important way for Diné people to take in knowledge, because, especially for earrings, they are so close to the person’s ears. “This adornment is one way of listening,” he says.

In Riege’s hands, the objects worn by a human-devouring monster become alluring. Visitors are encouraged to touch them, as the texture is a part of the experience. “Sometimes when you tell people you can touch it, they’re so afraid to, but it’s something that I really welcome,” Riege says.

The invitation to feel these sculptures asks the viewer to participate in a kind of choreography: one that began much earlier, in the making of them. Riege sees the work of dyeing and sewing as being propelled by memory.

“I let the judgment of my mind be put in the backseat, and let my hands figure out what they wanted to do before my mind or my voice or my language decided for me,” he says. It’s a kind of dance, something that Riege says he’s always doing, whether at the loom, around his home, or at the club.

“When you’re at the loom, your body’s moving,” Riege says. “It’s like a repeated action. Your hands are dancing with these strings. Or with with braiding or crocheting, your fingers are dancing with this material.”

Born in New Mexico, Riege says he was destined to become a weaver. “There’s this Navajo taboo, that if you’re pregnant and you hold a weaving comb, your kid’s going to be born with extra fingers or toes,” Riege said. “I was actually born six toes on my right foot. It was removed when I was one year old.” His fate was sealed when his mom touched a comb before he was born.

Eric-Paul Riege, (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́), 2021. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [5], 2020. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [3], 2020. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Besides the six soft sculptures, the exhibition at Bockley includes a composite of multiple works that are shown together. One of these is a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́, a giant loom that takes up nearly half the length of the gallery. Riege says he learned from Szu- Han Ho, his mentor and thesis chair at the University of New Mexico, that you are never supposed to leave a loom unfinished. He believes in that, but was going through a dark place, and left a loom unfinished for months. Finally, he came back to the loom and realized the ghostly strings of the loom, that hold the presence of absence as well as the absence of presence in their skeletal structure, were finished after all.

“I was thinking about the ones that have passed on in my life,” Riege said. The empty loom stood for family members who have died, but also for the Navajo Livestock Reduction. During the 1930s, Diné weavers couldn’t keep up with their practices because the U.S. government sold and slaughtered their sheep and horses, which severely affected the tribe’s economy and way of life. Riege also thought of people in his family and community who were forced into boarding schools where they weren’t able to continue their craft.

Riege saw the absent weaving as a holding place for their memories. “Their story is woven within this empty loom,” he says.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [2], 2018–21. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́), 2021. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

Eric-Paul Riege, jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1], 2018–21. Image courtesy Bockley Gallery.

The piece also acts as a kind of frame for two photographic prints, my god, YE’ii 1& 2. The two prints are suspended within the taut strings, facing opposite directions. Both prints have a black background and an amorphous, textured shape in the center. Look closely, and you see elaborate regalia and the shape of Riege himself caught in motion by the camera.

Understanding weaving itself as a performance, Riege sees his performative works, like the one documented in the photograph, as a way to honor the movements that go into weaving. “Being a weaver, you’re constantly moving your arms and interacting with this being,” Riege says. “It’s a very slow process, one that grows over time. It’s why I perform for so long, to represent the slow, minuscule growth of a weaving being made.”

Photography—itself a documentation of a performance that is responding to the craft of weaving—then becomes a part of a piece made from an empty loom. The interaction between all these works offers ways for Riege’s art to be repurposed, and actually reborn.

“I think about the many lives that things can live,” he says. “I don’t consider anything I do as finished, or having a death. In a way it’s always a cycle.”

At times, Riege wonders if he’s actually from the future. “I feel like I live in like a constant state of nostalgia, but then also deja vu,” he says. “Which is sometimes a little terrifying.”

Eric-Paul Riege: (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́) runs through July 10, 2021, at Bockley Gallery, 2123 W 21st Street, Minneapolis, bockleygallery.com.