Domestic Disturbances

Hannah Dentinger reflects on Robb Quisling's new show, "(ISP) Individual Service Plan," on view at the DAI. She finds it to be an incisive exploration of modern domesticity, by turns lyrical and lurid, and evidence of a playful, sometimes dirty mind.

GLANCE TO THE LEFT AS YOU WALK INTO ISP (INDIVIDUAL SERVICE PLAN): New Work by Robb Quisling and you will spot woodcuts depicting domestic scenes in muted primary colors, images that will do nothing to prepare you for what is to come. Enter the main gallery space, and you are confronted with shocking color: lurid yellows, greens and purples that resolve themselves, after a moment, into photographs of — yes, you thought right — prophylactic Jell-o molds.

A woman’s hands, her fingernails painted a 1950s-era pink hue, empties lime and lemon Jell-o out of condoms that lie wrinkled on a bed of — it takes another moment to identify the garnish — green and purple cabbage. It’s a new take on that Minnesotan staple, Jell-o “salad.” The traditional marshmallows and canned pineapple are here replaced by plastic figurines: teddy bears, diaper pins, storks carrying bundles are all suspended within the gelatin like flies in amber.

The Cabbage Patch Series, as Quisling dubbed the photos, plays with the myths surrounding conception and birth often spoon-fed to children. In one picture, those pink-nailed hands tuck into a succulent Jell-o phallus with a knife and fork (what Freud would make of this, one can only imagine). A playful, dirty mind shapes much of the show.

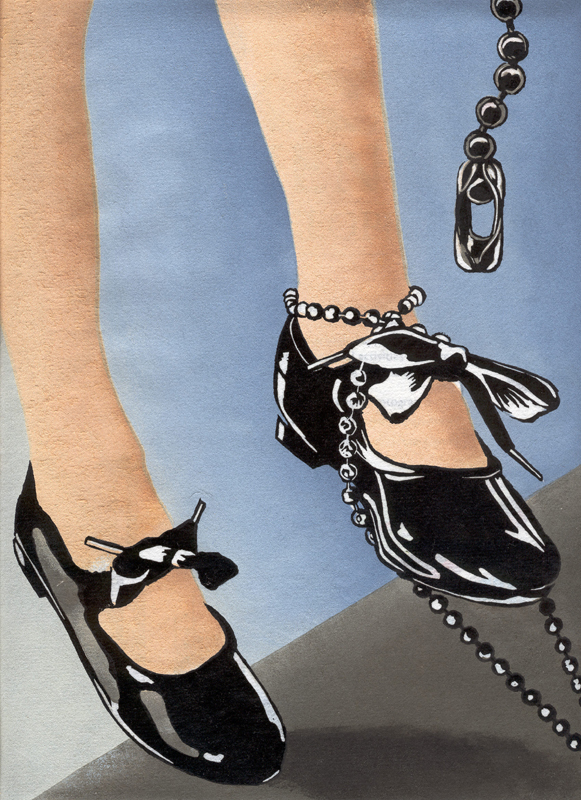

One series of color woodcuts depicts a rubber plug dangling above a drain’s dark opening from a ball chain — the phrase itself reminiscent of “the old ball and chain.” The chain reappears in another print wrapped around a pair of bare legs that, with their patent-leather Mary Janes, recall those of a child’s doll. As DAI Operations and Development Manager Christie Culliton, who gave me a tour of the exhibition, remarked, the picture plays an innocent image off a darker undercurrent suggestive of bondage.

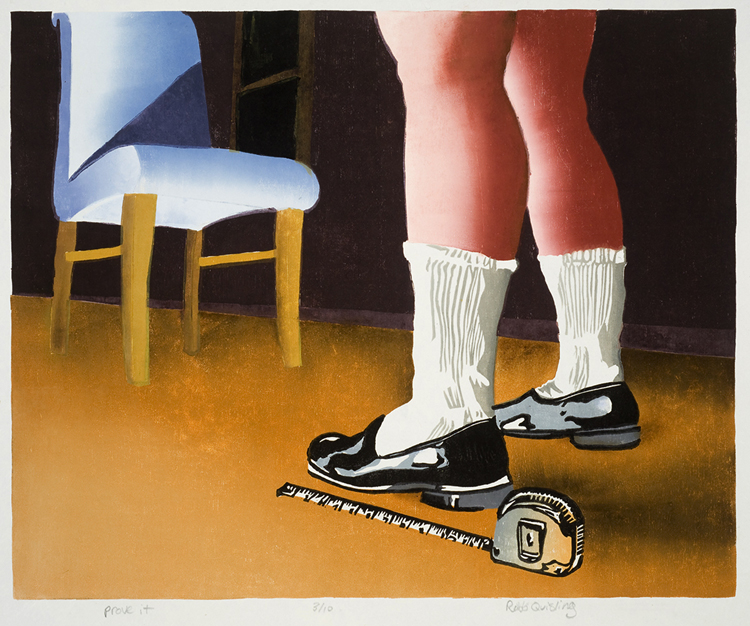

Quisling’s professional background in mental health services has come into play in his work before; and the new exhibition is constructed, in part, around the idea of the “service plan,” a set of personal goals for people with disabilities. “In order to be viewed as successful,” Quisling writes, “people with disabilities often need to prove their abilities,” and the accomplishment of domestic tasks (dressing independently, eating an entire meal) is rewarded, sometimes in the form of desirable leisure activities like watching television or “art time.”

These rewards, Quisling explains, provide “external validation” to the successful client. “This type of proof is common in the art world,” he continues, inviting the audience to “play along” as he “pretend[s] to be a successful artist.”

Quisling’s own Individual Service Plan is detailed at the entrance to the exhibition. Each item begins with the statement, “I will,” and includes such goals as:

- “Exhibit appropriate social interactions in order to earn art time (or in order to be perceived as normal in our society).”

- “Improve domestic skills, including meal preparation, in order to earn art time (or in order to be perceived as useful to my family).”

- “Obtain gainful employment in order to earn art time (or in order to be perceived as productive in our society).”

Thought-provoking and amusing though they are, these statements reflect a certain tendency on Quisling’s part to over-explain, to answer the questions that his work poses, on behalf of the audience. I would have preferred that the artist leave out the parenthetical explanations, letting viewers draw their own analogies.

________________________________________________________

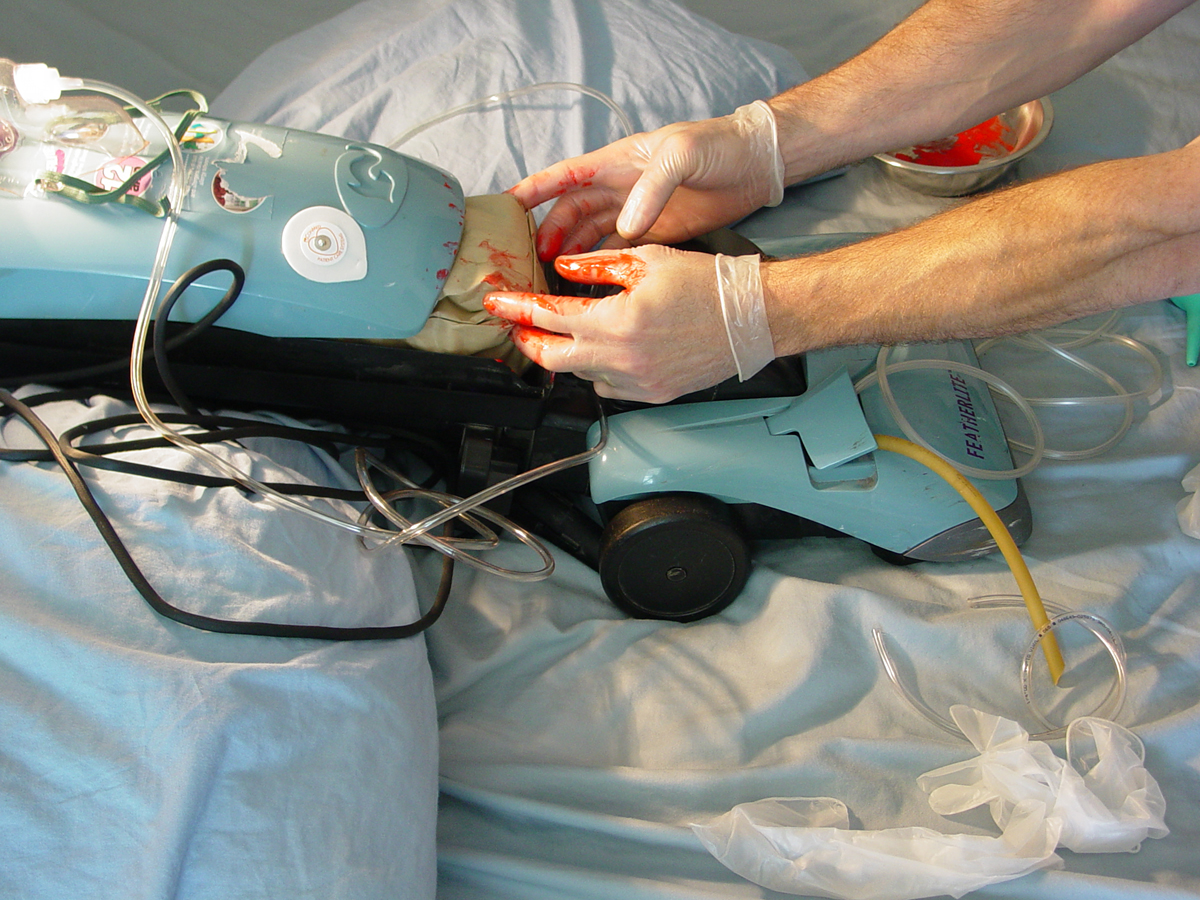

In one image, a vacuum bag is perched in a child’s high chair as a human hand proffers a spoonful of dust and steel wool. In another, a nurse’s bloodied, gloved hands remove the vacuum bag from the machine in a surreal hospital delivery scene.

________________________________________________________

That said, the work on display leaves plenty of room for the viewer’s imagination to play; Quisling provides an ample number of mysterious, irreducible images for you to puzzle out on your own. Take the series of photographs called Vacuum Birth. In the first photo, a vacuum cleaner’s hose snakes by human legs curled on a bed, suggesting a post-coital scene. In the next image, a vacuum bag is perched in a child’s high chair as a human hand proffers a spoonful of dust and steel wool. A nurse’s bloodied, gloved hands remove the vacuum bag from the machine in a surreal hospital delivery scene that constitutes the final photo in the series. Quisling’s “baby” is a skewed but literal take on the age-old idea: from dust we come and to dust we shall return.

Absorb the vacuum baby, and you are ready to move on to the interactive Feedback Machine Installation. Quisling has constructed two listening stations, each consisting of black vinyl rests mounted on brackets and equipped with rather scary leather restraints. The viewer leans in and presses a large yellow button to listen to recordings of Quisling critiquing his own work — harshly. At a third station, the viewer then reads one of three pre-scripted critiques aloud. A small digital camera perched nearby captures the “performance”: as the viewer reads, she appears on a television screen around the corner, where other visitors can watch her, unseen.

Culliton remarked that Minnesotans may find this portion of the exhibition especially challenging. “It’s been my experience that it’s very difficult for people from the Midwest to be direct and, especially, to offer a critique,” she told me.

From the supplied criticism, I chose to read the following: “This looks like you had a sleepover and started playing with your camera phone. It’s hard to see how this could matter to anyone.” Culliton was my unseen audience. The experience was unsettling, to say the least.

A medium better suited to the passive-aggressive Midwesterner is the exhibition comment book. Actually, several visitors to Quisling’s show expressed themselves with vehemence uncharacteristic of Minnesotans.

A selection of comments I noticed the day I visited:

“WTF”

“Offensive, unartistic.”

“Waste of time, space, materials…I didn’t like this.”

Of course, Quisling anticipated these possible criticisms of his work in his work. In fact, his self-critiques are far more devastating than the responses these casual viewers cooked up. But don’t take Quisling’s, or those anonymous visitors’, word for it. Take mine: this cabinet of marvels is not to be missed.

Exhibition details:

What: (ISP) Individual Service Plan: New Work by Robb Quisling

Where: Duluth Art Institute, Duluth, MN (George Morrison Gallery)

When: The show will be on view through May 31, 2009

About the author: Hannah Dentinger writes on art and literature.