Digging Up the Ghosts of Modern Dance

Emily Gastineau reviews "Appalachian Spring Break," the latest from choreographer Scott Heron, which revives (and plays against) the well-worn gestures of Martha Graham.

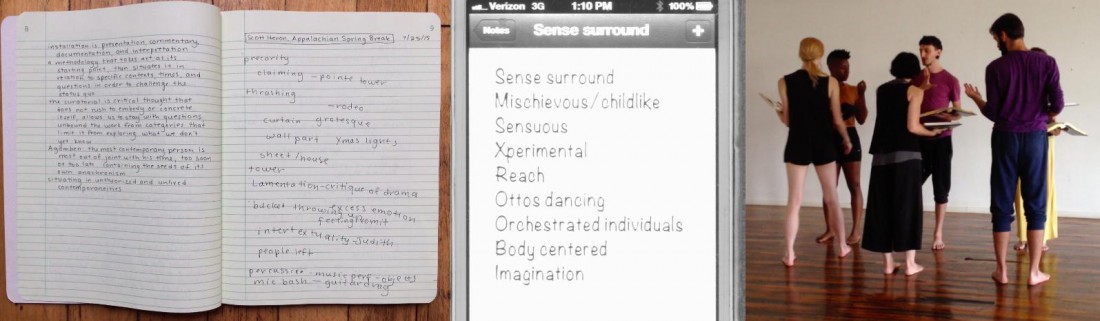

I’m sitting in the audience at Bryant-Lake Bowl, waiting for Scott Heron and Brendan Connelly’s new work Appalachian Spring Break to begin, when Judith Howard calls down the aisle to me. She asks to see a page from my notebook and offers to make it a fair exchange by showing me a page from the notes app on her iPhone. It’s a list of descriptors she captured while viewing an improvised dance performance: textures, associations, and oppositions. I pull a book out of my backpack, the source of the content on the notebook page I, in turn, show her. Judith opens another file on her phone, a rehearsal video from earlier that week showing a group of dancers “reading” the encyclopedia via gesture as well as speech. “What an intertextual experience!” she says, before removing herself to her seat.

The curtain opens on two white men playing clarinets, their faces and hands emerging from holes cut roughly into a white sheet. A sign, labeled “fanfare,” hangs from one of the clarinets, and the men play them like they’re just beginning middle school band—their fingers hit the keys all right, but the results are ungodly, irreverent squeaks. The two men retreat stage left, amidst a tangle of cords, instruments, and colored Christmas lights. Both men thrash against the wall, take their instruments apart and emit noises into the microphones. It’s stripped down. It’s dissonant. It’s rough and DIY. They treat the instruments not as means to an end (i.e. music), but merely as objects that can produce a range of sound. The roughness, the lack of preciousness, reminds me of Guitar Drag—though I wonder if the reference to a hate crime might be going too far.

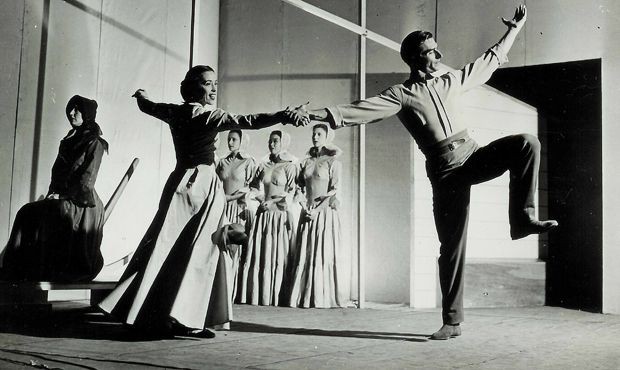

Or, perhaps the comparison is appropriate. Guitar Drag appears on the surface as an avant-garde exploration of the materiality of sound, but actually references complex histories of space and violence in American culture. And the source material for Heron’s and Connelly’s piece— Appalachian Spring, by modern dance foremother Martha Graham—is itself an iconic statement on Americanness. Graham commissioned composer Aaron Copland to write the score for her ballet, which premiered in 1944; the work portrays an American community in pioneer garb, complete with a preacher, a bride, and a groom. Graham’s piece culminates with the bride and groom’s installation in a newly-built farmhouse, a set designed by Isamu Noguchi. The work bears many of the hallmarks of Graham’s oeuvre, including her innovative physical technique, use of abstraction, and interplay between individual and community. As an American mythology, however, its narrative is predicated on violence: traditional gender roles, compulsory religion, and settler colonialism all undergird Graham’s portrait of a pioneer marriage.

In the work I’m seeing tonight, Scott Heron materializes in the aisle, his head covered in a white sheet that is lit from underneath. The sheet comes off to reveal four LED reading lights sprouting out of his temples, illuminating a series of exaggerated facial expressions. Wrapped in a toga, he approaches a makeshift tower far upstage, built from stage risers and topped with a piano bench. He climbs to the top of the five-foot tower and balances on his toes. It’s a rickety structure trembling with each adjustment of his feet, and eventually he needs to to catch himself on the ceiling. He descends to don a pair of pointe shoes and begins to climb to the top again, this time leaning heavily on a wooden dowel. The box of each pointe shoe and the end of the dowel make the same hollow thump as he lands the three points on each level of the tower. At the top again, he stands as a precarious monument. It’s quite an apt revision of Graham’s imagery—an homage to the American spirit in less confident times, where the structure could crumble at any moment but the climber hasn’t lost his nerve.

Throughout the piece, Heron employs composed, dramatic facial expressions and ersatz mime. It’s a takeoff on Graham’s highly theatrical style, and an implicit critique of drama in dance. I suspect that the gestures may be taken verbatim from a Graham piece or a ballet. They are performed with lifted eyebrows, earnestness, and gravity—but in a contemporary context, such aestheticized theatrics read as humorous and ironic. This is where the piece leans towards the “spring break” side of the title, with overwrought displays of emotion and an outrageous form of catharsis. The recurring mime sections often tip into the grotesque: in one instance, Heron’s movement takes him face-first into a bucket of water, as if he’s a college kid vomiting in Cancun. But the image isn’t static; he blows into the water, adding another layer to the sound score. It’s no accident that a prominent re-enactor of Graham’s work today does so in drag—like Heron, bringing both camp and sincerity in equal measure.

I recently reread an argument I love from the book Making Your Life as an Artist by Andrew Simonet. He compares the artistic process to the scientific process, in that both artists and scientists begin with a question and ultimately present their findings. He writes: “Like scientists, at the end of our research, we share the results with the public and with our peers. Some research is ‘basic,’ useful primarily to other researchers. Some is ‘applied,’ relevant to everyday life.” In a climate where art is compelled to try to reach a broader and broader audience, I am wont to stick up for the basic research, the artistic questions that work to advance the form without necessarily appealing to mass culture or trying to translate for viewers without deep knowledge of art history. A piece as highly referential (and intertextual) as Appalachian Spring Break seems to me to fall in this category of basic research. I know I connected to the piece most as a fellow practitioner with a solid grasp of dance history and the shared experience of wrestling with that history. Indeed, the general public’s preconceptions about dance as a site for rarefied emotional intent have a lot to do with the essence of Graham’s work. On the Saturday night I attended, a group of viewers walked out in the middle of the performance, perhaps because what was presented didn’t square with those expectations.

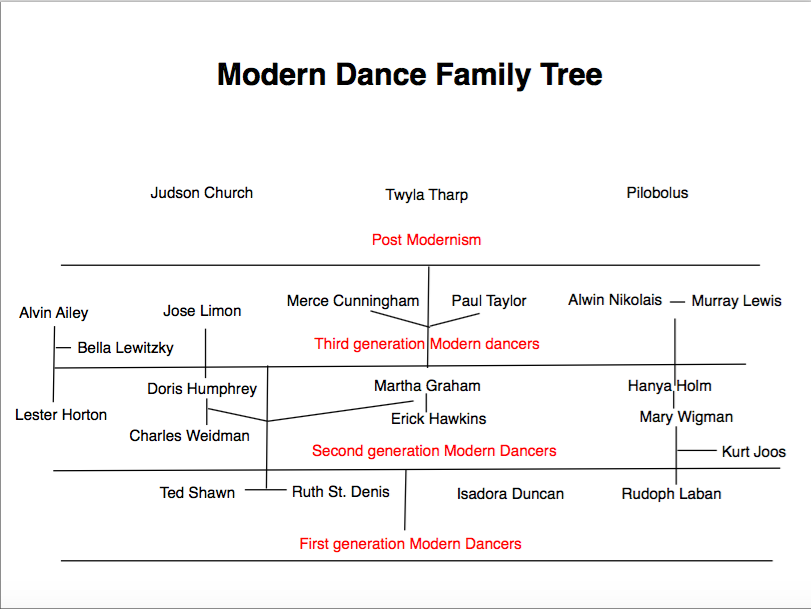

So, with that knowledge of historical timing, I wonder: Why revisit Graham today? The critique of affected drama in this piece places Heron in a long line of choreographers who have propelled their work in different directions away from Graham’s dramatic conventions: Erick Hawkins towards flowing movement, Merce Cunningham towards anti-narrative abstraction, Judson Dance Theater towards everyday gestures. While the aesthetic of Appalachian Spring Break is contemporary, the ethos is early postmodern. Digging up the ghosts of modern dance doesn’t feel pressing to me, but Heron and Connelly’s performance convinces me that there is plenty there yet to uncover. It calls to mind one the pages in my notebook, with this thought (from Agamben, paraphrased by Terry Smith): The most contemporary person is the one most out of joint with his or her time.

Emily Gastineau is an independent artist working in and beyond the fields of dance, performance, and criticism, and Program Coordinator for Mn Artists. She collaborates with Billy Mullaney under the name Fire Drill. They work along the disciplinary boundaries of dance, theater, and performance art, conducting experiments around the notion of contemporary and how performance art is meant to be watched.