Designing Rural Futures

Camille LeFevre reviews "Rural Design," architect Dewey Thorbeck's innovations in 'design thinking' about sustainable rural planning, based on an exhibit at HGA Gallery in the U of M and Thorbeck's book by the same name.

In 1845, John O’Sullivan, editor of The Morning Post newspaper in New York, declared that it’s the American people’s “manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty.” Westward, ho, went the pioneers. Many of them hitched their wagons and hopes to the ideology of “Manifest Destiny,” as it was widely publicized, along with 160 acres of native, unbroken prairie to call their own, made possible by the 1841 Homestead Act**.

That historical narrative and its environmental, racial and cultural repercussions—along with the metal pole sheds, silos, underground tornado shelters, and often-dilapidated wood barns and farmhouses that were an integral part of my childhood—is the sum of my knowledge about rural design. That is, until Twin Cities architect Dewey Thorbeck, founder of Thorbeck Architects and of the Center for Rural Design at the University of Minnesota, published Rural Design: A New Design Discipline.

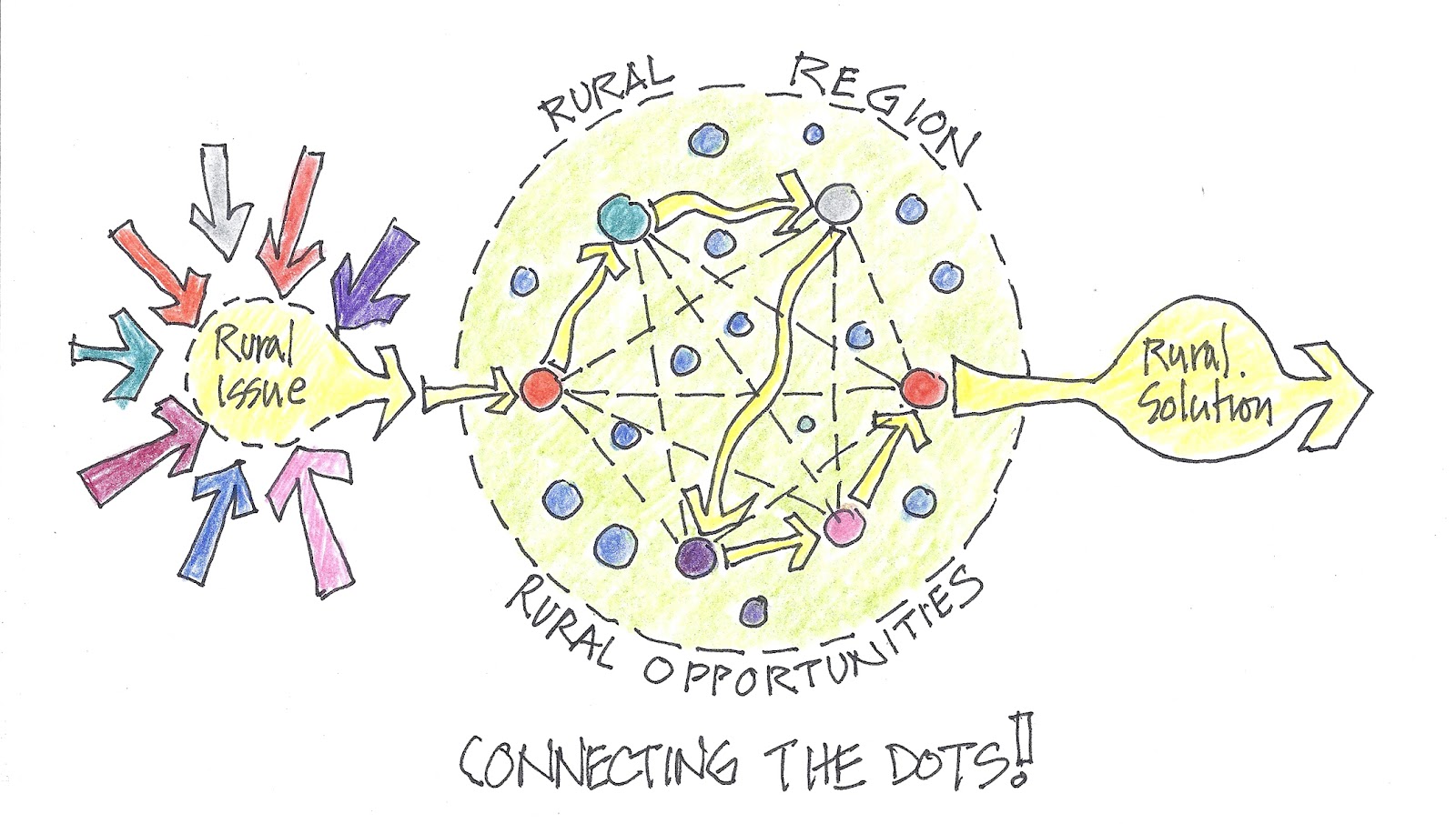

The first book “about the emerging field of rural design,” as it’s described in the foreword, Rural Design goes beyond the design of buildings in rural areas to encompass the design of food systems, factory farms, landscapes and communities using evidence-based research. In other words, rural design “is about design thinking as a means to utilize research knowledge and translate that evidence through the rural design process to benefit rural society.”

It is a flexible discipline, because the evidence gathered is culturally based and relies on existing environments and ecosystems, civic engagement and community workshops. “Human and natural systems are dynamic and engaged in continuous cycles of mutual influence and response,” Thorbeck writes. “Rural design provides a foundation from which to holistically connect these and other rural issues by nurturing new thinking and collaborative problem solving.” What comes of such design thinking and interdisciplinary solutions includes ideas, tools and support for change.

_____________________________________________________

Thorbeck imagines rural futures “internally driven” by communities that are profitable and sustainable, which empower their citizens and encourage innovation.

_____________________________________________________

In his book, portions of which are also reflected in the exhibition of the same name currently in Rapson Hall at the University of Minnesota, Thorbeck delves into the histories, environments, cultural forces, landscape patterns and buildings that have shaped rural heritage around the world. He discusses how research on rural issues can inform and instigate changes in economies, renewable energy and ecosystem health. He presents and dissects case studies, offers specifics on rural-design strategies, encourages interdisciplinary connections (with science and art).

He also imagines rural futures “internally driven” by communities that are profitable and sustainable, which empower their citizens and encourage innovation. Thorbeck’s objective, it could be said, is to inspire a transformation in how everyone thinks about, and works and lives on rural land.

Today, the population of the Great Plains is rapidly emptying out again, in a reverse of westward expansion. Still, temporary workers are flocking to the Plains to capitalize on money to be had from new industries. Communities are struggling, for instance, to figure out how to house the recent deluge of frakking employees. A once-controversial idea, the Buffalo Commons, proposed by Deborah Epstein Popper and Frank J. Popper in 1987 (which would return 139,000 square miles of the Plains to native prairie), seems to be occurring of its own accord thanks to these population shifts, without official intervention. And, with global warming and its ongoing droughts, old-timers are predicting another Midwestern Dust Bowl to rival that of the Dirty ’30s.

Such challenges, Thorbeck writes, “provide opportunities for creative and innovative land-used solutions…. that protect the rural environment while promoting rural economic development and enhancing rural quality of life. The time to act is now.”

***

In 1841 the government of America passed an act that allowed people to purchase 160 acres of Plains land for a very small price. A further act passed in 1862 divided 2.5 million acres of Plains land into sections or homesteads of 160 acres. People could now claim 160 acres of land. The only requirement on their part was that they paid a small administration charge and built a house and lived on the land for at least 5 years. [Return to text]

_____________________________________________________

Related exhibition and book information:

Rural Design: A New Design Discipline is on view at the HGA Gallery in Rapson Hall, on the University of Minnesota’s Minneapolis campus, through March 10.

Rural Design by Dewey Thorbeck was published by Routledge last year, and is available in bookstores everywhere.

_____________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a Twin Cities arts journalist and dance critic.