Dance Review: Colin Rusch’s Guide to New Dance

Lightsey Darst is working out what the New Dance might mean; much is still up for grabs

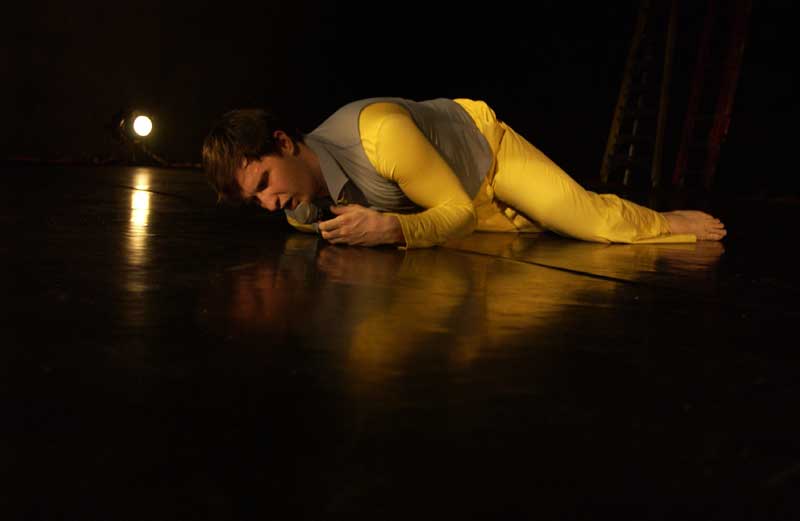

At the end of Colin Rusch’s Guide to New Dance, three dancers (Colin Rusch, Jane Shockley, and Morgan Thorson, who will be replaced by Otto Ramsted for the March dates) dressed in flexible versions of ordinary clothes twitch, leap, clutch at each other, and fall while a single musician/composer (Jonathan Zorn) plays distorted harmonica over previously recorded synthesizer tracks. The lighting is unsympathetic and we understand that what we’re watching is improvised (within a certain structure), out of the control of any one artist, and anything or nothing could happen. It’s natural, simple. That’s not a criticism: the dancers are inventive, charming, and brave, and their bodies collide in shapes I could watch for hours.

The first half hour of the performance, though, consists of jokes and monologues about dance, faith, eternity, and the intersection of the mundane and the cosmic (Kierkegaard, stadium dust). Why? It feels like an indoctrination, as if Rusch thought we needed to be prepared for the dance, put off-balance, stripped of our expectations; at the same time, it’s peppered with dance in-jokes (“My name is Colin. . . and I’m going to initiate movement from my intestines”) that certainly amuse the choir, but mean nothing to the dance heathens who have come into the theater by accident. Nothing is easier to watch than talented and skilled players tumbling and playing: those who lose patience with the elaborate mimes and promenades of a story ballet, or feel threatened by beautiful bodies doing beautiful things, or tire of the earnestness of modern dance, can all enjoy the childlike innocence and lightheartedness of improvisation. So why do we need to be introduced to the performance?

During a long monologue about Abraham and Isaac my mind wandered to what I wanted to see more of: these dancers, dancing. What is a dancer, in this new world? Not a beautiful (carved, hollowed, instrumental) body in space; you can see those in ballet performances, but these dancers look like ordinary people, and Chrystina Hanson’s wonderfully awkward clothes (nylon, boxy, bright, out of a children’s TV show) even emphasize this.

These dancers don’t exhibit any particular school of training; they’re highly trained, but they throw that away before they get to the stage; their movements come from daily life, not Cechetti, Graham, or Limon. And these dancers aren’t an embodiment of the choreographer’s thought: Morgan Thorson’s broken-ankled falls (she must have the cartilage of god) remain distinctive from Colin Rusch’s midbody-motivated fits and undulations and Jane Shockley’s bemused sways and curves. These dancers aren’t the visible emanation of the music, either; so far as there is music (not melody, not a steady rhythm) it behaves as an equal partner, just another improvisor on stage.

I tried saying a dancer is someone who doesn’t fall when you think she will, but then Thorson fell, so I said instead that a dancer falls well; but it wasn’t so much that the fall was graceful as that nothing broke and the fall turned into something else; maybe a dancer doesn’t stop moving, but then Thorson stopped and looked out at us with a Dutch doll face.

The new dancer is unpredictable, physically brave, shameless; an expert in daily movement; childishly playful; the new dancer escapes definition, except that he or she is a participant in the new dance.

What, then, is this new dance? Consider four musicians jamming together on stage. The sound is sometimes awful, sometimes sublime, but always changing, moving, refusing to fix in any one pattern. Imagine the same thing for dance: three or four dancers playing around, throwing their bodies into each other’s arms, listening to each other, making new shapes each night. What a pleasure that would be to watch!

But back to the monologue of Abraham and Isaac: why did Rusch choose to retell that story at such length? What sacrifice was he talking about? What do we have to be ready to sacrifice to enjoy or practice this new dance? The work becomes unstable; there are no variations to teach to younger dancers; there is not even a style to pass on, since the styles of the individual dancers are inimitable; a moment of improvised brilliance is just that, a moment, and then it’s gone. We have to give up the pretense and expectation of beauty, the artifice. We have to give up the stories and big emotions and live off raw movement, collisions, falls, walks. And dancers will have to accept a different kind of audience: people who talk during the performance, get up, go in and out, kiss and argue, pay rapt attention one minute and ignore the performers the next. How will all this turn out? Will we be moved, lastingly interested, fed? We can only find out by watching more.

This performance feels (appropriately) more like a blueprint than a finished piece—notes for a future performance. Rusch exposes more of the iceberg of theory than an audience needs. And this isn’t the new dance: it’s one of many new dances. But the dancers show the fascinating possibilities of improvisational dance, its humor and brightness and abandon. Where will this guide take us next?