Chick Flicks

These days, accomplished film pros many of them women see no need to head for LA to make their way in the industry. Britt Aamodt talks to a slew of MN women working in the business about the innovations revolutionizing how we make (and see) movies.

YOU MUST HAVE BEEN LIVING IN A REMOTE SIBERIAN VILLAGE for the past two years if the name Diablo Cody doesn’t ring a bell. But, then, maybe you’re not good with names. So here’s a refresher: Diablo Cody is the 30-year-old screenwriter who, at the 2008 Academy Awards, walked away with the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for Juno. And here’s the North Star connection: this Illinois native got her start writing for City Pages, and she was living in Minnesota when she penned the screenplay.

Cody has since decamped from Minnesota to seek the A-list networking only Hollywood can provide—which makes you wonder if living in LA is a precondition to “making it” in the film industry. But before you lament the loss of another talent to the coasts, consider that Minnesota has a gazillion women working in film; and many of them, thank you very much, are quite happy to stay right here.

Why? According to the women interviewed for this article, they’re sticking around for Minnesota’s well-trained pool of producers, directors, cast, and crew, and for the seasoned infrastructure that’s been developed to support them all—maybe not in caviar and Masaratis, but with enough tangible reward to keep the dream alive from project to project.

_________________________________________________

Thanks to a little thing called the digital revolution, more films are being produced for less money and in a lot more places, including the Twin Cities and small-town Minnesota.

_________________________________________________

But you can’t talk about women in film—or men—without discussing the biggest thing to hit the industry since sound in 1927. It’s called the digital revolution, and it encompasses a bevy of innovations like the Internet, digital video (DV) cameras, wireless, and high-definition—which all add up to one humongous cost savings for the indie filmmaker. For starters, a camera that once cost $50,000 will now only set you back two grand. This means more films are being produced for less money and in a lot more places, including the Twin Cities and small-town Minnesota.

Women With Vision

Women’s stories don’t sell. At least that’s what Hollywood thinks. Take a look at this year’s crop of summer blockbusters: Iron Man, The Incredible Hulk, Wanted, and The Dark Knight Returns. What do they have in common, besides their comic book origins? A strong male lead and a story that, on the surface at least, plays primarily to a male audience. People concerned about the under-representation of women in film lament that the last great summer blockbuster targeted to women was 1997’s Titanic. The movie made a killing at the box office, despite a “romantic” storyline that concluded with a sinking ship and the death of 1,523 passengers.

One thing you’ll notice about Minnesota’s women in film is that their conception of a chick flick bears no resemblance to Hollywood’s. In fact, most of these filmmakers aren’t even working in narrative film, opting instead to make documentary features and shorts, using their cameras to delve into real people and real stories.

_________________________________________________

‘Women’s stories don’t have to be about women—they can include men as main characters, but still come from the lens of a woman and reflect a knowing of the world through that gender.’

_________________________________________________

“It’s important to me to tell stories you don’t normally hear,” says Joanna Kohler, a self-identified activist and Minnesota Women in Film and Television board member, who has been directing and producing social documentaries since 1998. “And, traditionally, you don’t hear women’s stories. A [woman’s] story can include men and have a male as a main character, but still come from the lens of a woman and reflect a knowing of the world through that gender.”

Kohler’s films range across subjects like the problem of exploitation in youth services to coverage of activists working in Israel. Her documentary Boxers followed seven amateur female boxers at the Uppercut Boxing Guy in Northeast Minneapolis as they trained for the world’s largest, international boxing tournament. The “gee-whiz” factor is what initially attracts audiences to Kohler’s film: Wow, did you know women boxed? And why would they risk their looks and their femininity in the ring? Kohler’s power as a filmmaker lies in her ability to elevate the topic beyond a glib conversation about gender; she silences those kneejerk questions by showing her protagonists, first and foremost, as simply athletes facing the next challenge, who are balancing their desire to win against a fear of failure.

After two years in production, Boxers premiered at the Walker Art Center‘s Women With Vision festival in 2007, a festival specifically formatted to promote work by women filmmakers both here and abroad. Sheryl Mousley, curator of film and video at the Walker, took the Chicago-based festival Women in the Director’s Chair as a model when she sat down to create Women With Vision.

“There are so many women making feature films internationally, I thought it would be great to bring those international films here,” says Mousley. “I also wanted [to include] a local component, but without setting them apart. I thought if we set them apart as ‘Here are the Minnesota films’ it would diminish them, as if they were being given special consideration.”

Mousley’s solution has been to intersperse Minnesota and international films over the three-week festival. She also emphasizes the director-audience interaction, setting up question-and-answer sessions post-screening “so that the people who made the films can be there and can talk about them, and the audience can be engaged in that,” Mousley explains.

Women With Vision has provided a forum for several talented local filmmakers, among them Melody Gilbert, who is something of a legend for producing four feature-length documentaries in just five years, with a sixth (Fritz: The Walter Mondale Story) set for release this October.

You say want a (digital) revolution

Gilbert’s background is broadcast journalism. “You go out in the morning to shoot and, by that night, you have a story to broadcast. It’s great training–you learn how to work fast and to know what makes a great story,” observes the filmmaker.

Gilbert’s stories are quirky, offbeat, and sometimes hard: her films have looked at people who amputate parts of their bodies (Whole), at children whose inability to feel pain causes them to injure themselves (A Life without Pain), and at daredevils who skirt the law to investigate abandoned factories and sewers (Urban Explorers). She’s had screenings at prestigious film festivals, won awards, and has had work broadcast on the Sundance Channel. _________________________________________________

‘The joy of doing a documentary is you can have the story be whatever you want it to be.’

_________________________________________________

But she couldn’t have done any of it—or not as quickly and independently, at least—without the innovations of the digital revolution.

“As a journalist, you have to show both sides of the story. The joy of doing a documentary is you can have the story be whatever you want it to be. So, when these cameras [digital video] came out, there was no choice. I had to walk away from journalism,” explains Gilbert.

Digital and high-definition video cameras are empowering filmmakers across the spectrum, because they’re relatively cheap and they’re easy to use. Cristina Cordova was living with her partner Juan Antonio del Rosario in Puerto Rico when the idea struck them: They should produce a web series. “This was 2005, right at the beginning of web video, or what they called vlogging then,” remembers Cordova. “The first thing we got was a little Sony consumer camera, and we started shooting scenes from our window.”

Their next step was to move to Minnesota “away from family and friends and obligations, so we could just focus on the film,” explains Cordova. In spite of some bumps along the way, the couple eventually produced Chasing Windmills, one of the first weekly series, with a continuous narrative, to be made for the web. Windmills lasted two seasons (with no less than the New York Times begging for a third), and stood at the bleeding edge of what has since become a relative onslaught of online series now posted to blip.tv, Revver, YouTube, and other web-video devoted websites.

The field of animation has seen its own revolution, in which computers have overtaken traditional cell animation. Fans have variously praised and criticized the new computer-generated look of the resulting work, but animators like Bridget Riversmith are learning to combine the best of both worlds, taking advantage of technology while holding onto the handmade quality of traditional methods.

That Riversmith was even able to produce an animated piece is a nod to software technologies which have miniaturized processes that, in the ’80s, would have utilized a whole room staffed with a crew of animators. For her 2007 short Birds at Night (Might Fall), Riversmith scanned a series of watercolors and then animated them using Photoshop, Flash, and iMovie.

“I didn’t even know how to use these programs at first,” admits Riversmith. A full-time visual artist who always wanted to animate, she got her break through a friend she met at an artist residency. “My friend Annie was putting together a show in Chicago for artists trying a new medium. So, I went out there; did some storyboarding on the way. And Annie sat down and showed me how to use the programs.”

Her crash course in animation paid off. Birds at Night (Might Fall) is a lush vision of a boy and girl flying over a dreamlike world; it caught the eye of some powers-that-be, too. Riversmith’s short was picked up by IFP’s Cinema Lounge and by MNTV, a collaboration of the Walker, Intermedia Arts, IFP, and TPT.

Money makes the world go around

Film is a costly medium. Even given affordable technology and inexpensive web marketing, a filmmaker who wants to take her work beyond that of a hobbyist needs money—whether it’s to hike production values, which might mean hiring crew and an editor, or to get it in the hands of agents and distributors. Indies like Juno and Napoleon Dynamite were successful, says screenwriter Miriam Queensen, because they offered something original, something distinctive to the viewer. But even more importantly, these movies succeeded because they could be produced on a relatively small budget. No galactic cruisers battling in space—just actors feeding each other lines.

The film industry is financially conservative, says Queensen. “They don’t want to spend money on something that’s not going to make money. That’s why you get a lot of Hollywood sequels and remakes, because those are a sure thing—or so they think.”

If you’re a screenwriter, like Diablo Cody or Queensen, the way to get your script made into a movie is to hook up with a producer. Queensen’s first screenplay—Clara, about 19th-century concert pianist Clara Schumann—attracted several producers the old-fashioned way, by entering screenwriting contests; but she also got their attention the new-fangled way, via InkTip.com and other similar sites that serve as meeting grounds for screenwriters and producers. On these websites, screenwriters post loglines (short synopses of scripts) and, sometimes, even entire scripts. Likewise, producers post what types of stories they’re looking for.

The cool thing is that sites like InkTip.com work. For Queensen, the best part of this new-fangled, online approach to seeking out producers is that she doesn’t have to move in LA to get her screenplay noticed; her latest, a thriller called The Red Seal, has also been optioned. Yet getting a producer’s attention is only the first step in the long process of pulling a movie together. The producer still has to gather the production money.

With Chasing Windmills behind her, Cordova has turned her skills to producing other people’s films. Currently, she’s unit production manager for Abnormally Normal, a web series filming in the Twin Cities and directed by Julie Rappaport. “It’s a huge production—480 pages of script just for the first season,” says Cordova. “Now, we have a little snag. The money was there for pre-production, but it’s not there yet for production.” Part of Cordova’s job is to knock on doors to pull the funding together.

_________________________________________________

The business end of filmmaking is one of the hardest parts to manage because filmmakers are artists. They’re in this to make movies. Pulling together money

and making deals aren’t where their skills or passions are strongest.

_________________________________________________

That constant need to wear two hats—the creative filmmaker hat and the money-making, business hat—has prompted independents like documentarian Gilbert to search out partners. She found one in Jan Selby, a marketing professional in business for herself when the two met at IFP’s producers’ conference. The women have since founded Darn Good Documentaries.

The business end of filmmaking is one of the hardest parts to manage, explains Selby, because filmmakers are artists. They’re in this to make movies. Pulling together money and making deals aren’t where their skills or passions are strongest. “I know how to run a business and I’m good at marketing,” she says simply. “When I met Melody, she had people like Best Buy coming to her for work. But I thought, what would happen if she went out looking for them?” With Darn Good Documentaries, Gilbert and Selby are bringing the authenticity and genuineness of documentary filmmaking to corporate clients eager to connect with their audiences—employees, other businesses, and consumers—in new ways. The hope for Gilbert and Selby is that money from this commercial work will feed Gilbert’s creative projects.

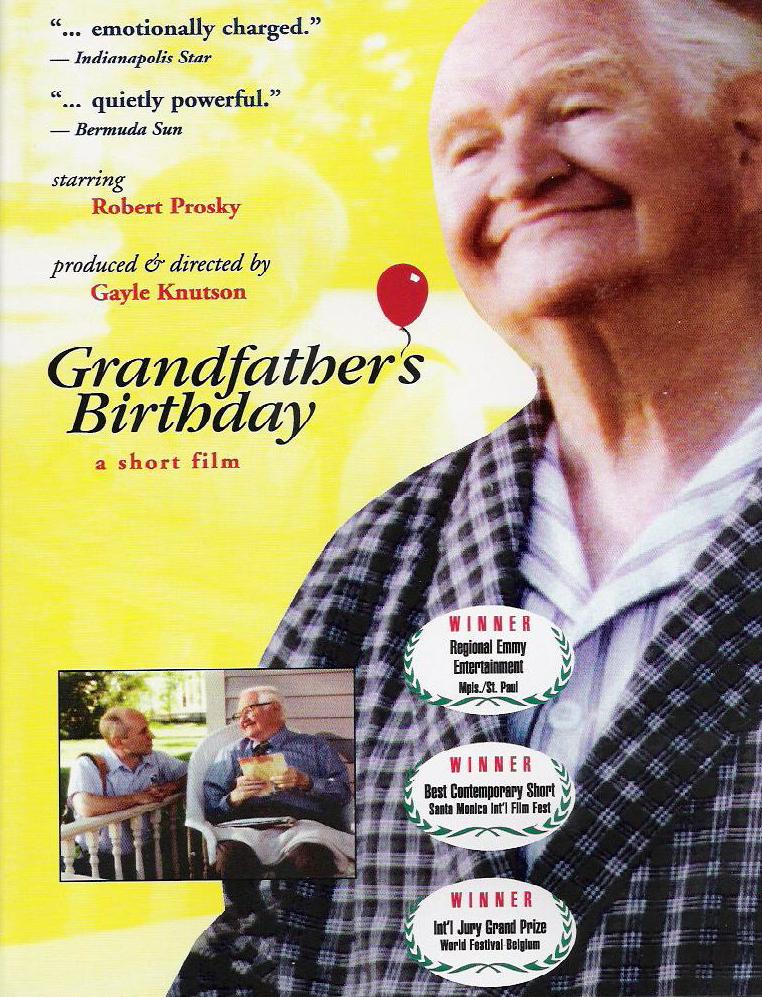

Filmmaker Gayle Knutson also hired an executive producer for her narrative short Grandfather’s Birthday, starring Hill Street Blues veteran Robert Prosky. Grandfather’s Birthday won 24 awards and a regional Emmy, but it’s a type of project Knutson is finding harder to reproduce. “It’s funny how, as you go along, you have to work with less and less,” she says. “What money is there is in fellowships, but only a few people get those—and there are a bunch of us going for them.”

Knutson’s latest projects have been documentaries—If there were no Lutherans, would there still be green Jell-O? and Prisoner 32,232. The reason she and other independents don’t make more narrative films, says Knutson, boils down to cost. “A documentary, you can pick up a camera and film it on your own or with one other person. Once you start choreographing for a movie, you involve more crew. You hire a writer. You block things out. You have storyboards. It just takes more money and more time.”

Follow your bliss

Mythologist Joseph Campbell is famous for coining the phrase, “Follow your bliss.” The idea is that if you follow what you love, what you love will bring you success. But then, Campbell may have been referring to the less tangible kinds of success, like the feeling you get after a job well done, and done simply for the joy of it. Mark Twain called that making your vocation your vacation.

Speaking of her decision to leave the realm of corporate videography to go into filmmaking for herself, Knutson says, “When you work for money all the time, especially in a creative field, you’re painting someone else’s canvas. I wanted to paint my own canvas.”

Gilbert puts it like this: “I had to make these films. It was just me and my camera. I didn’t have to get a crew or a grant, or anything—just me.” And Kohler: “I don’t make a lot of money (although, hopefully, that’s going to change). I do it because I’m not used to making a lot of money, and because it’s a passion; it’s the relationships, my quality of life.”

Despite the financial ups and downs of the business, these filmmakers are still making film a full-time or nearly full-time vacation. But there are others—many, many others—who are still putting on the suit every morning, punching the clock, and then rushing home at the end of each day to film the next scene in their no-budget horror.

“Technology will change the industry,” predicts Queensen, who teaches screenwriting classes at The Loft. “It’s becoming more democratic. I don’t know if that will necessarily lead to better product, but hopefully it will lead to more variety.” But one thing is clear: the next generation of filmmaking, whether you’re talking Minnesota or Manitoba, is about the individual voice. “These [emerging filmmakers] are do-it-yourselfers who don’t want to be part of the system at all,” says Walker film and video curator Mousley. “Now, almost everybody has their own equipment where, before, you had to be part of an organization or a school [to have access to tools of the trade]. So there’s a whole new freedom in that.” And Mousley wonders, further, “Will there be a new film language coming out of this?”

Only time and technology will tell.

About the author: Britt Aamodt is a freelance writer living in Minneapolis. She loves the arts, meeting new people, and grocery shopping.

Related Links:

Bridget Riversmith’s website

You can watch a clip of Bridget Riversmith’s animated short Birds at Night (Might Fall) on her website.

Cristina Cordova and Juan Antonio del Rosario, were the creative team behind the 2005-07 weekly web series. Watch episodes on the Chasing Windmills site.

Darn Good Documentaries

Jan Selby and Melody Gilbert, founded Darn Good Documentaries to bring their experience and the techniques of documentary filmmaking to business and organizational clients.

Gayle Knutson’s website

Director Gayle Knutson has produced several documentaries. Her narrative short Grandfather’s Birthday, starring Hill Street Blues regular Robert Prosky, won a regional Emmy.

IFP Minnesota: The Center for Media Arts

IFP Minnesota supports and promotes the work of artists who create screenplays, film, video, and photography in the Midwest. From novice to experienced media artists, IFP MN provides ongoing programs and services to ensure that your voice is seen and heard.

InkTip.com

InkTip was created in 2000 to help screenwriters gain exposure for their works and sell them to producers. Over 2000 production companies are registered with InkTip and use the site to locate potential scripts.

Joanna Kohler’s website

Joanna Kohler has been directing and producing social documentaries since 1998. Her films have covered topics of exploitation, activism, and, in 2007’s Boxers, amateur women’s boxing.

Melody Gilbert’s website

Melody Gilbert is a documentary filmmaker who has directed and produced four independent feature-length documentaries in the past five years, with a sixth on the life of Minnesota politician Walter Mondale, premiering at The History Center fall 2008.

Minnesota Film and TV Board

The Minnesota Film and TV Board’s mission is to build and promote the state’s moving image industry as a force for economic growth.

Minnesota Women in Film and Television

The Minnesota chapter of WIFT was formally established in 2005 to educate and support women in film, television and new media.

Minnewood.com

Minnewood follows the independent filmmaking scene in Minnesota with filmmaker interviews, behind the scenes footage, and clips and trailers from locally-produced features.

Miriam Queensen’s screenwriting classes at The Loft

Practicing screenwriter, Miriam Queensen teaches beginning and advanced screenwriting classes at The Loft Literary Center.

Screenwriters’ Workshop-Minneapolis

The Screenwriters’ Workshop serves screenwriters with programs, weekly workshop groups, and events held in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area.

Women With Vision

Curated by Sheryl Mousley, the Women With Vision International Film Festival is held over three weeks in the spring and recognizes the unique contributions and perspectives women bring to the art of filmmaking.

A very short list of video-sharing websites:

YouTube

YouTube is a video sharing website owned by Google, and it’s the 800-pound gorilla of the free sites allowing users to upload, view and share video clips.

blip.tv

blip.tv is a video sharing service designed for the distribution and viewing of user-generated content, particularly weekly online series. Filmmakers like it because the site allows you to upload and stream the original, high-quality digital file (rather than a dramatically compressed, lower res version).

Revver (and Veoh, Brightcove, Blip.tv, and Metacafe)

If you’ve cultivated an audience for your work, you might consider posting on a video-sharing site which shares its ad dollars with you. Could be a nice boon if you’re bringing lots of eyes with you. Among these, Revver seems to have the most generous partnership arrangement—sharing 50% of the ad revenue generated with its “artists” who own the content; and giving a 20% cut of the revenue to “syndicators,” or those who share links with content on their own blog/website.

Vimeo

An up-and-comer in the video sharing marketplace; it’s known for being “family-friendly” and has a particularly easy-to-use interface; and, you can upload (but not stream) the original high-res digital file for your work.

Social Networking Video-Sharing Programs

Most of the popular social networking sites offer their own video-sharing programs: Facebook and MySpace both offer well-developed proprietary video services, for example.