Capturing Relationships: JoAnn Verburg

MPR's Euan Kerr spent a few hours with JoAnn Verburg just before her big show opened at the Walker. They talked about her camera, how narrative fits into her evocative shots, and the power of the lens to capture an ongoing relationship with the viewer.

IT MAY TAKE A WHILE TO GET TO IT but if you’re going to talk to JoAnn Verburg about her work, at some point you will need to have a conversation about her camera. She uses a large format camera, which produces negatives five inches by seven inches across. It’s a close relative of the kind you see in history books, balanced on a spindly-legged tripod with some mustachioed photographic pioneer proudly standing by. It’s a big beast, but it produces spectacularly clear and large images. It also allows the photographer extraordinary flexibility in manipulating the image—an advantage Verburg cherishes and pushes to its limit. She drops under the dark cloth that drapes behind the camera and peers at the image the lens projects on the glass plate inside. She can zoom in and out at her subject by extending the large accordion bellows on the front, and then mess with the angle of the lens so very specific parts of the picture are in focus.

“When I am underneath the dark cloth looking at those tree branches and whatever is behind them, I am really not thinking particularly,” she says. “I’m just looking at things. It’s almost like working with a piece of clay. You aren’t thinking about it, so much as you are just watching what happens when your fingers squoosh it.”

This kind of large format camera doesn’t have a viewfinder, and the image she sees under the cloth is upside down and back to front. “Which actually works for me for whatever reason,” she laughs. “It’s confusing for some people, but my brain adapts to that.”

Apparently, it’s adapted well. The Museum of Modern Art in New York has been collecting her work for more than twenty years, and her pictures are in major collections around the country. She’s a photographic star, but I wouldn’t know it from her manner as she leads me through a tour of her studio. There’s a spectacular panoramic view of downtown St. Paul outside her window, but the images on the wall are far more arresting.

Verburg leads me to the back of the studio, where she points to a large grayish-white photograph of a pyramid. “Can you figure out what this is?” she asks.

Actually, I think that may well be the operative question when it comes to approaching much of Verburg’s work.

She makes large color prints of things and situations that feel familiar upon first glance. Then you look again and spend some time with one of her photos. If pressed, you can’t say with certainty what you’re actually seeing. Her pictures of trees, people, household objects, and newspapers are imbued with ambiguity. But it’s a welcoming ambiguity, something which draws in a viewer.

And what about the pyramid? When she had the print made, the people working at the printer said they didn’t know she’d been to Egypt. She hadn’t. “It’s sand,” she explains, from a Florida beach where she sometimes vacations with her family. “And (the print) is actually the size of the sand pyramid,” she says further. “The thing I was hoping for is that you wouldn’t know the scale, and there wouldn’t be enough information for you to immediately read it. You might possibly read it as big or small; or you just might not know.”

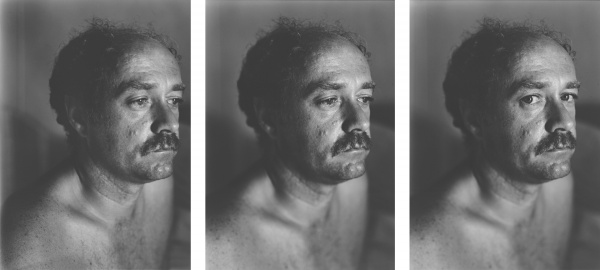

Verburg talks a lot about how people might relate to pictures. She has explored a number of subjects in her own work over the years: images of artists working at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and at the Walker in the 1980s; pictures of dancers swimming in a pool; images of her husband, poet Jim Moore; and photos of olive trees in Italy. But even when the images are relatively small, Verburg’s use of scale makes them approachable, literally on a human level. It’s important to her that there is something full size in each picture. Yet when asked if there is a story behind her images, Verburg quickly says no.

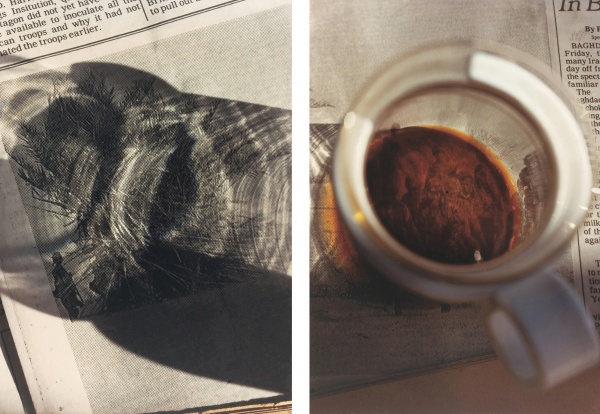

In fact, the narratives that do appear in Verburg’s pictures come from newspapers, which often appear in her images. Because of the scale of the pictures, it is possible to read not only the headlines, but some of the stories, too.

Her 2003 polytych Underground consists of six pictures arranged in a rectangle, three images high and two across. The top two images appear to be looking across some open ground at a wall or building. The middle two show a golden brown expanse of fallen leaves, with those in the foreground blurred, almost as if by tears; the bottom two feature a man lying on a park bench, apparently sleeping. Verburg points to the headline in one of the pictures, “In One Village Halting Progress,” and then to the subtitle, “New Grief and Grievances.”

“We all sleep with grief and grievances,” she says. “You can ignore it, but you can’t get away from it.” And for Verburg, her husband Jim, who is the man on the bench in these pictures, is “subject matter, not the subject.” When he appears in her pictures he isn’t Jim, he is Everyman.

“I think I have tried to drain the narrative out of my pictures,” she says. “I think it may be because if you get it (a story), it’s like coming to the end of a novel or a short story, and you are finished. I want my work to be useful and open-ended and provocative beyond any narrative ending.”

Instead, she hopes that her images will become part of viewer’s life experience and touch upon something else happening at that particular time—a recent conversation, or a reaction to a book. To illustrate her point, she talks about a painting she has visited year after year in a certain museum. She says she always takes her journal along with her when she visits this piece. When she’s there, she sits in the gallery and writes.

“I always describe the painting, but I always describe it at the moment in my life when I am looking at it. I have written about the death of my father while I’m looking at the painting; I wrote about my sister, some experience I have had,” she recalls. “Each time, I see it differently.”

She tells another story about how, on a recent overseas trip, she saw a woman taking pictures of herself near some water. “She was all by herself,” Verburg remembers. “There was no-one near her for a hundred feet on any side. And she was prancing around, with the cell phone pointed at herself, trying all different angles. She did a 360-degree turn. I was just completely in love with that moment.”

As Verburg explains it, those cell phone snaps by the water share a common element with her own large-format work. “It gets back to the doubling of time,” she says. “You can be in your place and in your time, but that can be shared with someone else. And that can be part of the moment in time that they experience later. I love that.”

She admits that photography can be a refuge, too. Two arresting images in her new show Present Tense were made during the week after the 9/11 attacks. Both show her husband sitting outside, reading the newspaper. (She has a rule that she only uses the newspaper from the day she is making an image in her pictures.) “It wasn’t that I wanted to capitalize on a great headline; [I used it] because I was devastated. My way of working my way out of deep emotional traumas is looking out through the ground glass at the world,” she says.

This brings us to JoAnn Verburg’s current challenge. In this brave new world of digital delights, Kodak has discontinued making the film Verburg has long used for her work on her large-format camera. She has a stock in her freezer (on the day I visited, she had enough for 300 shots). That number of shots would be barely a blip on the memory card of most cameras nowadays, but for Verburg they’re now a measure of the dwindling lifetime left for her old-fashioned camera. She’ll try to get Kodak to do another run of the film, but even in the freezer it only lasts a few years.

She’s worried, but not too worried. “I don’t know what I am going to do when my film is finished,” she shrugs. “There are many ways to make art; I remember hearing Chuck Close, who was paralyzed, talk about what he would have done if he hadn’t been able to use his hands again. He said ‘I would have made art with pipe cleaners.’ And I feel that way. I am not going to stop making art, I’m just not going to do it in 5” x 7” color.”

She pauses briefly. “And that’s too bad, because I’ve figured out how to use it.”

Indeed she has.

About the writer: Euan Kerr is a member of the Minnesota Public Radio News Cultural Unit.

What: Present Tense: Photographs by JoAnn Verburg

Where: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

When: The exhibition runs through April 20.

On a related note: come to “Contemporary Art in Conversation” with JoAnn Verburg on Thursday, January 24 at 7:30 pm. FREE tickets to this event will be available at the Bazinet Garden lobby desk beginning at 5 pm