Art and the Stop Line 3 Movement: Dio Cramer

An artist/attorney working in the Stop Line 3 movement speaks with the creator of some of the most ubiquitous art from the protests: on the function of organizing ephemera, how intellectual property works differently for art made in service of a movement, and not waiting for permission to do things

I first met Dio Cramer while working as an attorney in the Stop Line 3 movement. At the time, I did not know the 24-year-old, Minneapolis-based artist was responsible for some of the most ubiquitous art related to it, including, for example, her “red eagle” design that can be seen in photographs and livestreams from both the front lines up north and across the country (and also in many hours of police bodycam footage, as I know very well.) Now that the pipeline’s construction is finished—though there are still many open cases against water protectors—I wanted to talk with her about her experience as an artist supporting a movement, and to also discuss what seems to be the underacknowledged role that art plays in these spaces.

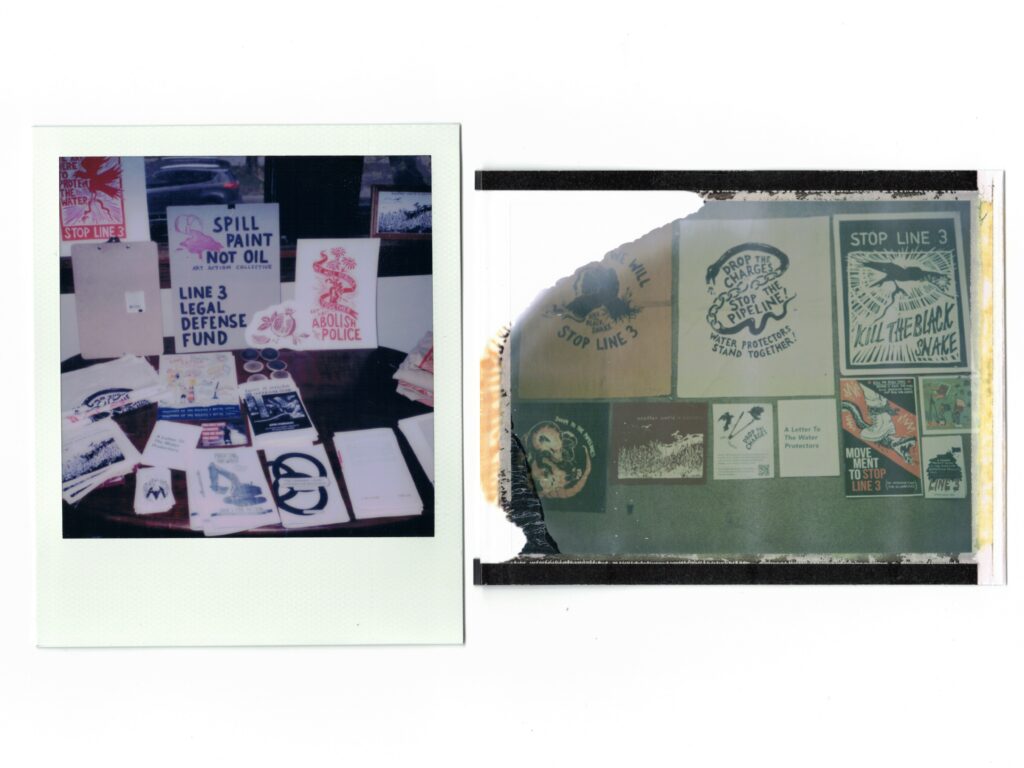

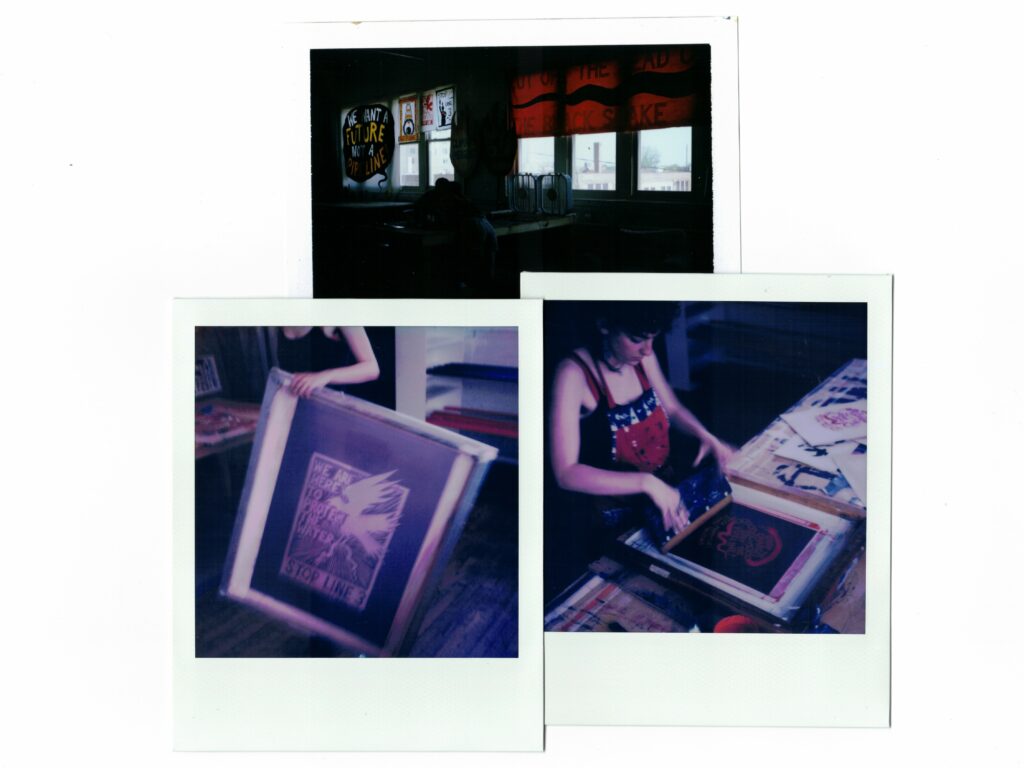

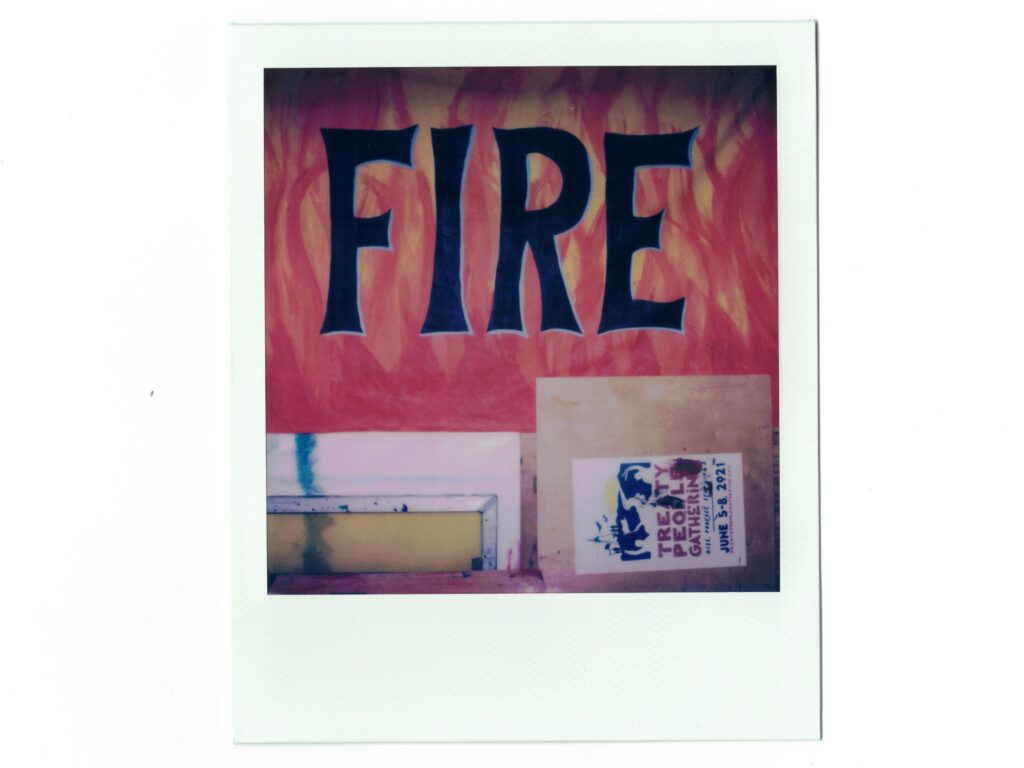

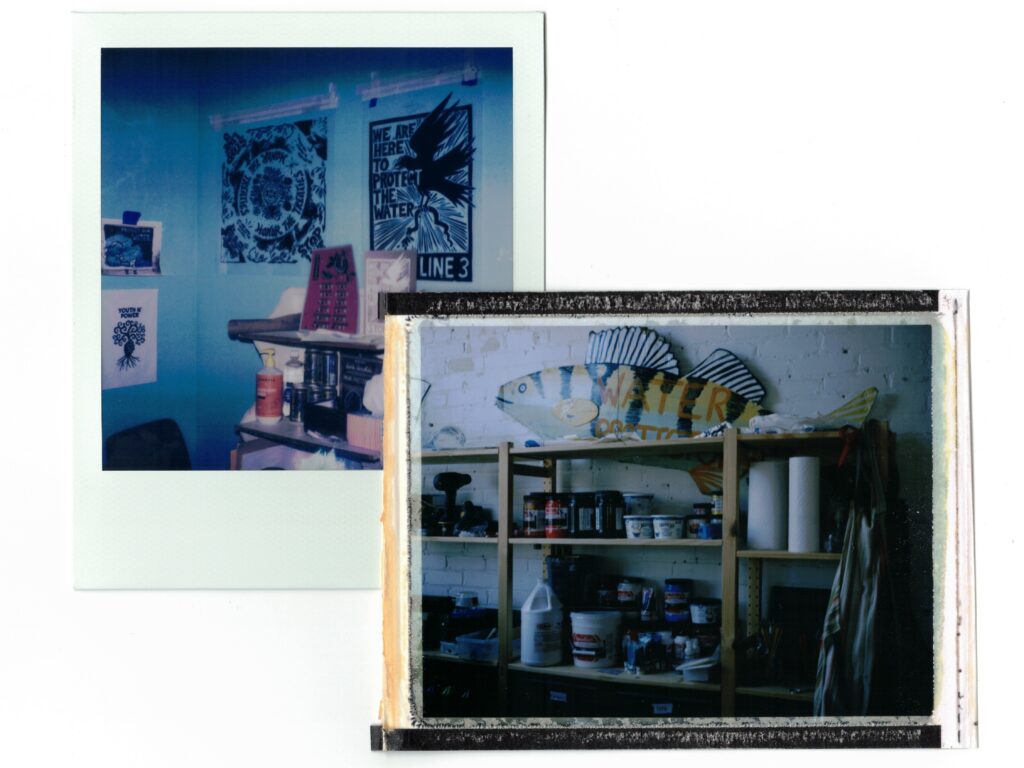

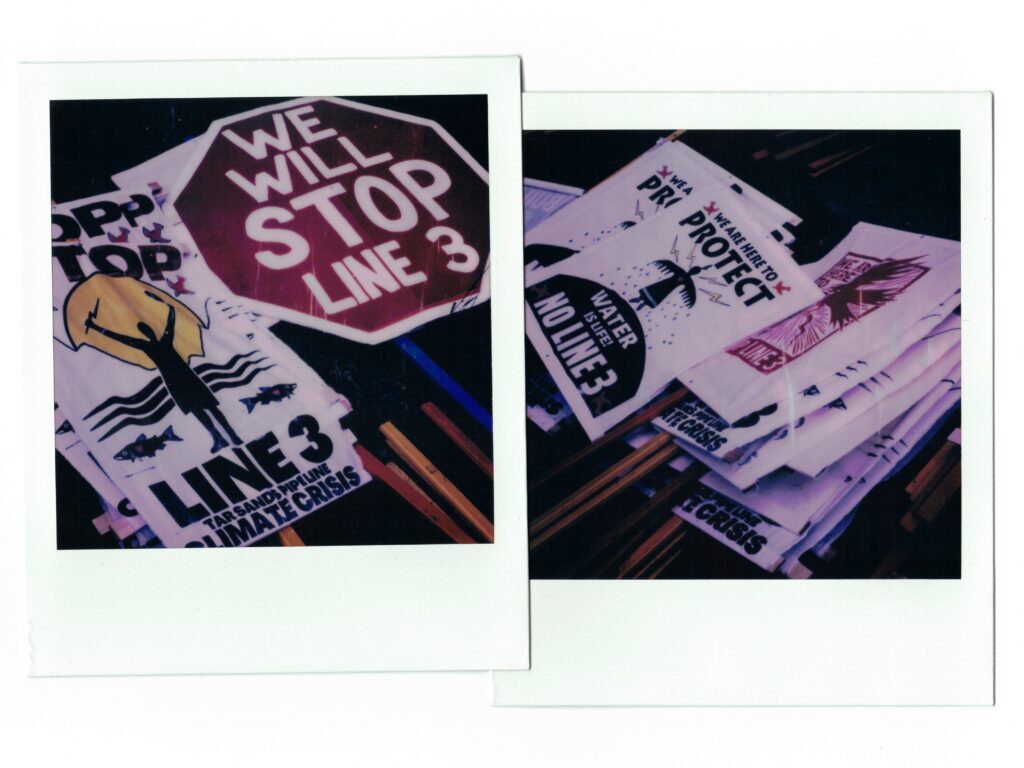

Every movement has its art and organizing ephemera, such as the shirts, signs, and patches that one sees distributed or worn at rallies and protests, but which, because of their purpose, are more likely to end up in shreds than a museum. Yet, far from being what some may call “agitprop,” such art creates the visual identity of a movement that serves to pull together the spirit of a community with shared purpose as it stands up for itself and imagines new possible futures. In this way, it is more like a type of public art.

Finally, although Dio is just one voice in a much larger conversation, I think her story is worth sharing because I know from my own experience that there can be a lot of anxiety among artists—or anyone—who wants to contribute their skills to a social movement, but are not sure where to start. Unfortunately, this can lead people to doing nothing at all in the end, and at this moment in history, as (it seems) one crisis begets another, each movement flowing into the next, we cannot afford to stop or slow down. This is it, folks.

When we spoke at the “Spill Paint, Not Oil!” art studio where she and others work, Dio told me that ever since she was a kid, there was always a link between art and activism. “My family was already involved in the activist world through art of different kinds,” she told me. Her grandfather was the folk musician and photographer John Cohen (of the New Lost City Ramblers) whose work captured the mid-century art scenes of Greenwich Village and San Francisco, and her mother, the late Sonya Cohen Cramer, was a part of the Seeger family and a talented artist and singer in her own right. Growing up in this environment just outside of D.C., she remembered going through all the fliers and prints that her family had made or gathered over the years. “My grandpa just had stacks of posters from all the shows they were performing in New York in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Not being a history person myself, and just someone who learns from the world around me, that was my introduction to that kind of grassroots art.”

After moving to Minnesota to attend Macalester College, Dio pursued her interest in art activism and joined MN350’s art team, which hosted “art builds” where anyone could show up to make banners and signs for upcoming events. This opened up new opportunities for her, including the chance to design MN350’s “Stop Line 3” lawn sign, which can still be seen around some neighborhoods. But when she graduated in 2020, she, like many young people, joined in the protests following the police murder of George Floyd. Doing so, though, made her think more deeply about how she could best offer her skills as an artist and organizer. So, she supported some of the groups painting murals, which she said was “a cool way to see artists and community members rise up to support the movement.”

That same summer, Dio raised several thousand dollars for mutual aid groups with her silkscreen print, “We Will Rebuild Together / But First Abolish the Police”—though when a Brooklyn Center police officer killed Daunte Wright the following spring, she decided to make the design open access, allowing it to be freely printed and used by anyone so long as it was not for commercial purposes. This was an approach to movement art that she learned from the artists Isaac Murdoch and Christi Belcourt of the Onaman Collective, both of whom did this with some of their designs during Standing Rock. As attention shifted from the aftermath of the uprising to the protests up north, Stop the Money Pipeline and NDN Collective invited Dio to contribute art to its open access “Defund Line 3 Art Kit.” Among other things, the kit had tips for printing images, creating banners, and making stencils. With its content soon popping up across the internet and in cities around the country, this kit helped create a consistent visual identity for the movement, the importance of which cannot be overstated. Afterall, it is through this that people not only literally see the movement but also understand its aspirations.

As a type of visual language, movement art has the challenge of compacting into a few symbols and phrases not only the issue but also its implied solution. Even more, it shares with fashion the fact that its message is not only the image, but also those who wear or carry them, which when captured by the photographer’s lens become its own image shared through different media. In this way, such art becomes shorthand for a whole movement or moment in time, making it as much about movement identity as it is about being personally identifiable. And as the world turns, the prints and patches themselves, with the originals often lost, destroyed, or in a private collection, become part of the historical landscape, the palette drawing heavy shades in our collective memory. Think of the Black Lives Matter sign, with its sharp contrast and bold text, an image tied forever to this decade and the many faces of the dead. The same goes for the Make America Great Again movement, which for being only four words on the page nonetheless evoke images of red hats and polyester flags. If you are anything like me, I suspect there must be at least one mural in your mind from the summer of 2020 that stands for the wellspring of art that spread across whole streets of plywood. Such things may not last forever, but they are far from being ephemeral.

If you google “Line 3 Protest,” you will find dozens of photos with Murdoch and Belcourt’s “Thunderbird Woman” designs, or Dio’s own works pinned to shirts and jackets or on placards held high in the hands of demonstrators. For Dio’s part, these include the design for which she is best known, which depicts a red eagle clutching a snake in its talons (the “black snake” being a common metaphor for an oil pipeline.) It reads: “We Are Here to Protect the Water / Stop Line 3.” Another depicts the black snake’s body merged with chains that suggest incarceration, handcuffs, repression—though in it the chains are broken, and as the snake coughs up what might be blood or oil, there is the demand that the state “Drop the Charges / Stop the Pipeline! / Water Protectors Stand Together!” Seeing all these photos compiled together can be a reminder of how movement art takes on a life of its own.

“I do think open access art is a really good way to contribute to movements,” Dio told me, though as we discussed the topic—while recognizing that the cut-paste/share-post nature of social media means that one has even less control over their work anyway—I asked if there were any downsides to this, especially when it is already hard enough sustaining one’s practice. She shared the story of a potential funder who was reluctant to pay for a movement-related project, despite admitting that her designs raised tens of thousands of dollars for their organization. Then there was the time that she saw one of her designs on a magazine being used to raise money. But even so, Dio said that “a lot of those organizations have done good things for the movement and have supported me in other ways,” explaining that her uneasiness stemmed more so from issues of consent and the co-opting of movement art by nonprofits. “I wish they would’ve at least asked,” she told me. “When it’s directly tied to raising money for a specific nonprofit, that feels more outside the boundaries of using it for the movement.” Still, she acknowledged that this just comes with the territory.

“As an artist working in a movement, you do lose some of the control over who gets to use your art than you would if you were just making it as an individual for the world.” To this point, she cited the example of the rainbow pride flag, which was created by the artist Gilbert Baker for San Francisco’s 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade. Baker’s original design included eight colors (later changed to seven, and then six) and has in the decades since inspired at least 30 variations reflecting the full diversity of the LGBTQ+ community. Another example is the iconic image of a clenched fist that symbolizes Black power and popular resistance, despite having gone through its own evolution. “After a certain point,” Dio said, “that art just becomes your service to the movement and then it’s everyone’s to use.”

Now, it should be stated that Dio is not an Indigenous person. I say this because I there is sometimes an expectation that anyone who talks about their movement work at length must—or at least should be—a member of whichever group is leading it. Over the course of my Stop Line 3 legal work, I met plenty of non-Indigenous water protectors who were eager to do more for the movement but soon backed off, because even though they wanted to be supportive and do the right thing, they didn’t always know what “the right thing” was. And I get it. After all, for anyone who feels called to action but doesn’t know where to start, it can be frankly scary going out to march alongside your neighbors while never knowing whether each step will hit the ground or someone else’s toes—no matter how much you look down. Trust me: I know how it feels to be anxious and self-conscious going into new spaces where you’re expected to leave a part of yourself at the door and open yourself to new ways of thinking and being in the world around you. And yeah, it can be tough finding the courage to do this when, despite your good intentions, it feels like you’re risking rejection or being “canceled,” but you also have to understand that there comes a point when all these fears just become an excuse for doing nothing.

When I mentioned this to Dio, she said it was something she noticed, too, and that it was this exact fear of messing up that “stunted a lot of things from happening.” But what she also saw were a lot of artists “just waiting for permission to do things. Sometimes that’s warranted, and other times the people you’re waiting on don’t want to be in the position of giving permission. You just have to try what you can. If you do things with genuine care and respect, you might still fuck up,” she said. “But if you have conversations with people who can ‘call you in’ to things, then you can change and adapt. Then you’ve given it your best try rather than waiting around until you have all the right answers to do anything.”

As for how she grapples with this, Dio explained that “I’m just trying to do what I see as the right thing for the groups of people I’m working with. There’s not much more to it than that, and at times I’ve been asked to step back from certain spaces and will gladly do so when it’s communicated to me.” Importantly, she knows that her willingness to take constructive criticism or step back in no way diminishes her role or the value of her contributions to a movement. “It can be my story, too.”

As more people become aware of how their lived experiences inform how they show up in a space, it is important that all of us be conscious of who is and isn’t allowed to share their stories or make art. Given the historic disparities between people based on race, class, sex, or neurotype, we really do need to be intentional in ensuring that the public conversation reflects the full range of a diverse society. But when it’s taken to its extreme, whether enforced by others or just within ourselves, it can be alienating focusing on the voice but not what it has to say. For example, I don’t know if I’m writing this as an attorney, Indigenous person, or artist (or just someone rationalizing their pin collection.) But I also don’t know if it matters. Nonetheless, I’m aware that whichever I declare here—or you presume—will turn what I want to say into a kind of masked fiction, rather than what is me trying my very best to sit beside you in these words and say: the fact that you are so concerned about making sure you do the right thing is its own proof that you are approaching this work from a good place. So, trust your intentions. And regardless as to those cynical comments about how the road to hell is paved, there is nothing else for us to do but approach both our art and activism—neither of which are mutually exclusive—in good faith and with kindness and humility. There is room here for all of us.

“The purpose of a movement is to get people from all walks of life involved and participating,” Dio said. “The more people you let tell stories and make art, the more people those stories will relate to and the bigger movement you will build. You have the autonomy to make art about the world and its problems, and you don’t have to wait for permission because no one will give you instructions or ask you to do it. You just have to do it.”

And if you’ve looked around, there is still so, so much for us to do.