Are We Black Yet?: On Blackness as Art

Drummer, composer, writer and professor of African American literature and culture Davu Seru explores a body of ideas belonging to a kind of "un-finishing school" from Coltrane and their excavated recording, Both Directions at Once, to the seminal sermon in Invisible Man and perhaps black literature which asserts "black is...an' black ain't", asking us along the way: "Are we black yet?"

“If we had not survived and triumphed, there would not be a Black American alive.”1

James Baldwin

“Black people have as their unique and true object blackness envisioned in itself and for itself.”2

X

In the quote above from James Baldwin’s essay “On Being ‘White’…And Other Lies”, Blackness can be read as either epilogue or interlude to an old book that many Americans have finally got around to reading but stopped short of finishing…having understood just enough to have an awkward conversation about it.

The text sits closed but (now that it is a part of us) it continues to call its readers, asking: “Are We Black Yet?”

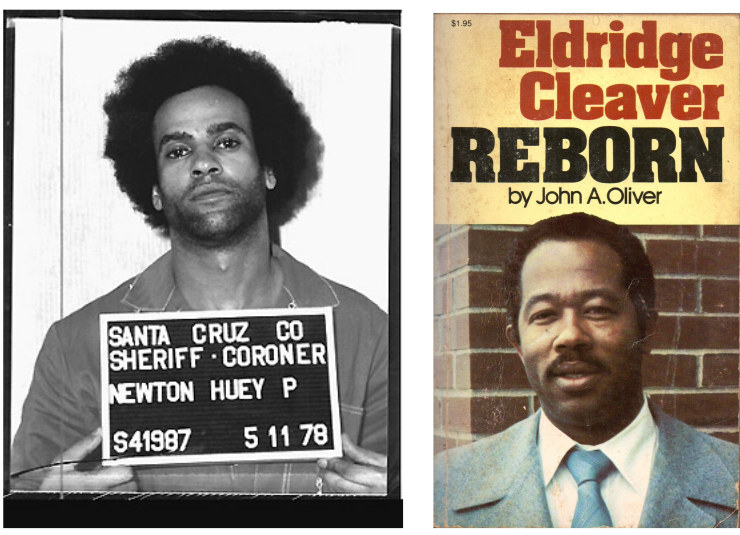

Where some of us left off, a Black Power patriarch was being charmed by Capital. Born-again and deferred. The fruit of an African Diaspora’s epic vision witnessed rotting on the vine while playing dead in the road among texts. And in mixed company—

Where some of us left off, a Black Power patriarch was being charmed by Capital. Born-again and deferred. The fruit of an African Diaspora’s epic vision witnessed rotting on the vine while playing dead in the road among texts. And in mixed company—

The Original Haste

Meanwhile, because we are required to be black matter and invisible Black lives, or dead: already black matter is so condemned to be other than white matter (white lives performed in bad faith) that it is charged with being opposite all matter.

This contingency and cancelling-out certainly nags at the ego that seeks expression in naming—it might even have us seeing double. But we remember: “two-ness” was DuBois’s warning and not his final word on the fact of blackness in the 20th century. Indeed, for DuBois, the charge was “to merge his double self into a better and truer self.”3 Eventually.

We remember also that, Ms. Toni Morrison told writer Cecil Brown, that, ironically, the agonizing split keeps you before your maker and “on your knees.”4 A beloved mouth agape in a reverent O—

And, so, you might say that—in order to secure our choice in this matter—we have taken to laboring faithfully in time for a field outside of confrontation, outside of the kinetic energy that prophesies the destruction of Babylon, U.S.A. Where black plays in the possibility that the temporary uselessness of abstraction and the culpable by-standing of self-mastery allows; and while witnessing.

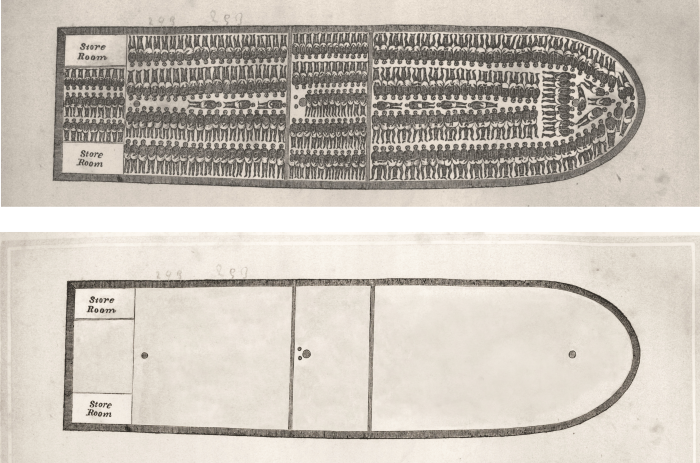

Boats in need of no blessing. Love, and a song of belief and disbelief which the Irish writer Samuel Beckett—of palimpsestic mind—might recognize as un-song. Which is an abbreviated subject—one which needs to remain open, unthought terrain…

Yes, blackness has something to do with water and the souls of folks who have assumed white lives. A crucible of ships and economic efficiency not intended for the merchant-kings of feudal Europe, but for the new property owner who will hide democracy between pages which will become useful only periodically; our intimate constituted just next door, primed for race-baiting. And, when all is said and done, that—to the corporations that own it—might turn out to be the real value of their labor.

Are we Black yet?

Many of us are too busy laboring (again: in mixed company) and now know better than risking definitive answers. Still, if we’re lucky, the answers will eventually issue from the kind of change that cannot be undone. And, seeing as the status of the unborn child never really followed the mother but always belonged to the policies of an outer room, we consider that naming remains possible.

But what does it take to imagine blackness as anything more than a sensational signifier of death and not-white? The sensualist Ad Reinhardt had this to say about the blacks that preoccupied the end of seeing life:

“A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high, as high as a man, as wide as a man’s outstretched arms (not large, not small, sizeless), trisected (no composition), one horizontal form negating one vertical form (formless, no top, no bottom, directionless), three (more or less) dark (lightless) no–contrasting (colorless) colors, brushwork brushed out to remove brushwork, a matte, flat, free–hand, painted surface (glossless, textureless, non–linear, no hard-edge, no soft edge) which does not reflect its surroundings—a pure, abstract, non–objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self–conscious (no unconsciousness) ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti–art).”5

Genesis of a cisgender object “as high as a man, as wide as a man’s outstretched arms” and who is just a few cubits away from salvation (as he’s been holding that place in line for some time and is bound to get his replacement soon). A body imagining itself as representing absence and illegibility before it’s mixed viewership. Figuratively spoken. Virtually speaking its ears into being. Without relations and, so, no need of a hearing or a death sentence. That is, compared to man who riddles in parentheses so as to avoid a sublime-but-inevitable conclusion.

Which is to say identity has some plot to it. But—for those of us who labor under black…which is all of us—it is our hope that it need not necessarily resolve…ever. Especially seeing as we appear to be stuck, operating at our least, in exposition—this essay included. Perhaps that’s black property: un-bounded perpetuity, rather than the end of times. Life-giving illegibility.

The sublime dissolve of the flood, if not for the maroon’s harvest. Black matter into night. A falling action without revelation by a people who live in time as if they know and knew they’ve been late.

Rather, in and out of time—we gather our relations and ask Ouroboros: will the circle of un-suffering be broken? Or will politicians continue to speak for the surplus in the language of our most eloquent models such that we don’t recognize them anymore? And who is going to do anything about it?

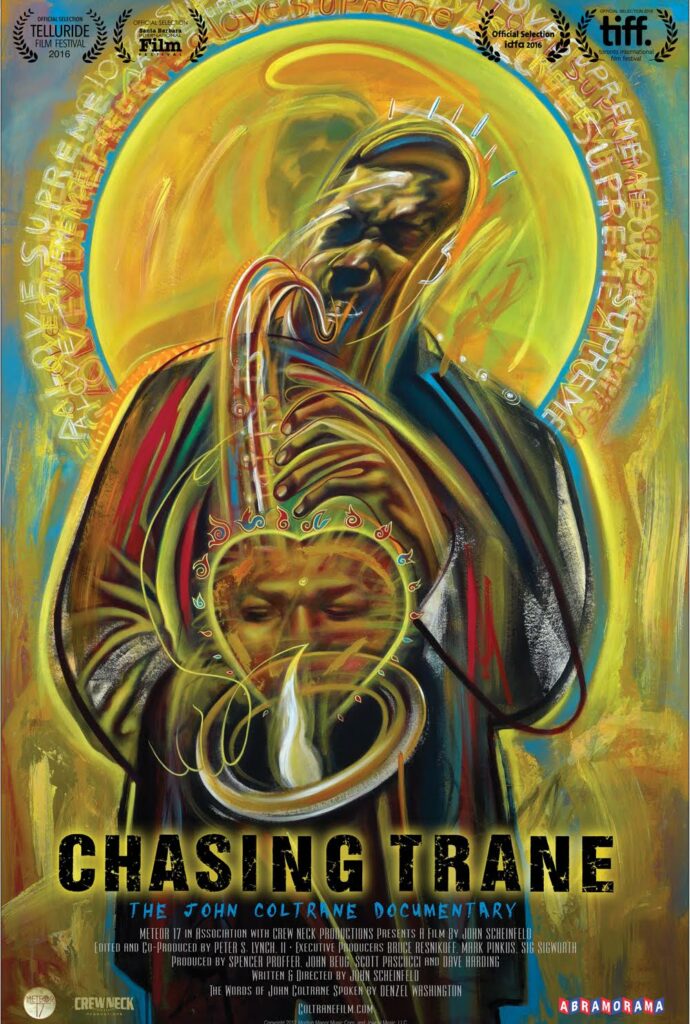

John Coltrane, who died without our permission a month and a couple of weeks before Ad Reinhardt, has recently been exhumed, and the experts have promised something revelatory at the end of that capital investment…with saxophonist Bill Clinton as an advisor on jazz populism and love to the seekers.6

But the glossy retrospective displays their damnedest to render energy, time, space and matter useless to the Black life we have set out to claim.

Still, the faithful know that Uncle Remus and Scheherazade remember continuity in the breaks of the book, that their perpetual signifyin’ has been insinuating on our behalf the whole time—even while money tries to speak for us. In fact—if we did not know better—we might trade all of the unseen footage of Trane and all of the February 29ths in time if they would just let it alone.

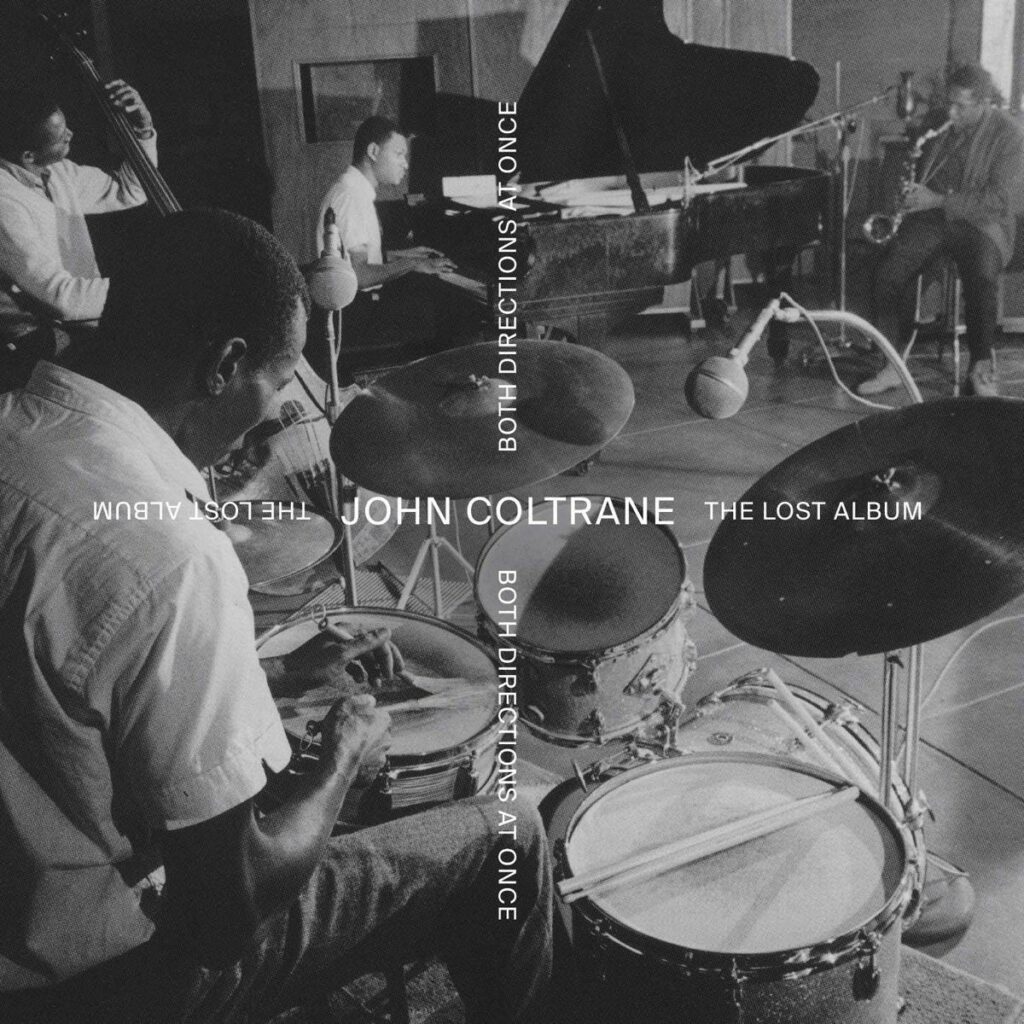

And if seeing is not believing, hear Both Directions at Once7: consumers playing loss with Trane playing at the crossroads, and splitting the tribe into at least 1), that market-driven group identity that composes a Coltrane fan-base before the fall, as opposed to 2) a group running on the clean coal of radical Black feeling. Before he objected abjectly to harmony as the white heights of verticality…when we’ve been talking black and ingrained folkish transcendence over clear, white coherence…for long enough to have already called it man. What Ad Reinhardt managed to feel but—lacking the green-tinted shades8—also strained to see, as Ad instead sought wisdom in an Orient where there are no black churches.

But Coltrane, the Prince of Peace, seems to say to a congregation of cursing cannibals:

“Now black is . . .” […]

“I said black is . . .” […]

“. . . an’ black ain’t . . . ” […]

“Black will git you . . .” […]

“. . . an’ black won’t . . .” […]

“It do . . .”

“ an’ it don’t.”9

Replace the speaker’s relations with bracket ellipses and we might illuminate something in black irresponsiveness: namely, that it has already been spoken for in the call. (Can’t you hear the curses loving you?)

Trane was the direct heir to a migration north, a boundless Jim Crowism and a series of Civil Rights movements that he transformed into the dynamic orature of religious new art and much more. Including an audience that was “black but comely as the tents of Kedar.”10 Un-song. Possibility. Statements without question. Neither lack, loss, longing nor “what did I do?…”. For Black’s—

“world was possibility and [black] knew it. [Black] was years ahead of me and I was a fool…The world in which we lived was without boundaries. A vast seething, hot world of fluidity, and [Black] Rine the rascal was at home. Perhaps only [Black] Rine the rascal was at home in it.”11

Like in movies where the advance guard of people with money spread sheets over old furniture before relocating. Except, between the sheets of Africa, Trane left an empty space.

The accomplishment of Coltrane at a crossroads seems to have been a kind of voice-leading to black-until…and the Trane lapse has provided an opportunity for other returns:

I, for one, often circle-back to Jean Toomer’s Cane (1926). Having written what had the potential of being one of the blackest books of the 20th century, Toomer would eventually give-over to the Manichees of Wisconsin and to signifyin’ on transcendence with: “I am neither black nor white nor in-between.”12 And Toomer had the right, according to the proto-postracial law guiding the effort. A right to the anxiety about a polarizing line that bends back to encircle like the rock that crashed through “the wind like the belly of a pregnant Negress” and into Kabnis’s cabin window down south. Or, in Toomer’s case, like fragments of shroud.

This violence as in that of William Faulkner’s, where the evening sun goes down behind the bottoms and where Nancy Mannigoe awaits the return of black Jesus who’s hell-bent on killing her contaminated child in utero.13 But, as with the Law of Beckett’s Godot:

“They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

All so that those of us in the enormous outer room download the next Kamasi Washington epic on iTunes. So that we will prostrate ourselves before the return of the guru from stellar regions to the civilization of the internet.

What’s Left to Declare?

Or is there too much to abject to?

Stepping away from Both Directions at Once, perhaps there’s a penumbra somewhere passing for something other than a text. An experience nestled behind eyes and ears that has not yet been spoken. A break.

And from the 2018 Chicago Jazz Festival—after being asked to stand for the national anthem–you listen to a memorial to Muhal Richard Abrams (read by a daughter of the pianist-composer); and then Amina Claudine Myers (the goddess meant to guide us over the threshold to black) moves from Debussy romance music to the Köln concert but in a storefront church; then a star AACM band emerges with Myra Melford, the spectral rogue dropped into the optic black.14

Mwata Bowden breaks the fourth wall and speaks for Chicago when saying about Muhal: “He put his hands on us…A collective that perpetuated individuality.” Muhal “…who opened up the gate.”

Rev. Eshu, the trickster and his riddler’s leavings: Is it part or whole? Or hole? Is the hibernation finished? Bear with us: Ari Brown, Leon Q. Allen, Harrison Bankhead and Reggie Nichols. As we suspend belief and look out for ironies to play against: namely, our reverent and bitter black church singing our un-song in a fortified tin can resembling Frank Gehry’s ear. A jazz institute longing for its secret name. Longing for its past black commodity.

You are there with the irony and have in mind earlier dialogues with Trane inheritors David Boykin and Jamal Moore who, like Kemetologists and archivists, live to circle-back to fundamental principles of ante-capitalist Black thought.

Transcendence stowed-away on the wings of the sankofa bird on the margins of the black city.

And then you are mindful of the park again, and then sheets of (sometimes blue) reverence again. Hey, Muhal and—as the Chicago Chamber of Commerce reminds you—Hey, Rahm Emanuel. And you’re left imagining black deaths on the other side of town where you’re playing later that night. And in order to not gentrify the place—which thanks to Harold Washington is remembered as Muddy Waters Drive—you, David and Jamal wrap bògòlanfini around your shoulders and headout for the hunt.

Thankfully, the next day, you hear Amina Claudine Myers and band on the Von Freeman Stage singing a love song. Looking for something true. You watch as the elder Alvin Fielder and Kidd Jordan15 sit and listen hard at Amina singing into the eyes of an African baby that you wish was you. And then of pain laid down with some noise. And the baby (call her “Orisha”) answers Amina: I am no longer as black as I have been made to feel. I am the flesh of sound and I ain’t dead yet.

The elders, Jordan and Fielder, stand for the love made possible by language…in a world where—if anyone has ever successfully talked themselves out of being killed—language returns as the God in search of her reader.

Raymond Williams—who also taught us to read a society obsessed with death and money—has been useful in describing The People’s Speech-act: “A vocabulary to use, to find out ways in, to change as we find it necessary to change it, as we go in making our own language and history.” Where we would need to be participants without belong. And perhaps that’s the best consensus we can stutter for

while, in

the stutter, we

con ceal as

much as we

say —as

This article was commissioned and developed by Mn Artists guest editor Chaun Webster as part of the series Blackness and the Not-Yet-Finished.