Anti-Ethnography: The Violence of a Civilization Without Secrets

Following a program of indigenous filmmakers curated by Adam and Zack Khalil, poet M.J. Gette chews on violence in ethnography, embodiment in archive, manipulation in documentary, and positionality in language.

What is ethnography? Here, short films

Tease out the long history of anthropological methodologies that treated indigenous people as endangered species—to be documented en route to the expansion of the West

In forms which are the opposite of singing:

A photograph—as currency of the archive

A mask—as a souvenir of the rising/razing Empire

A bone—as artifact of what was conquered

Writing—as evidence of history

A wax cylinder disembodying a voice from a language’s last living speaker

Or anything otherwise complicit under capitalism, the virtual model of “primordial cannibalism”

That severs all attachment to its meaning

To enable a general scraping/dispossessing of what is called “culture,” a word as empty and particular as “love,”

defined by its context and who performs its forensics—

I think the question “What is ethnography?” is answered with the same metrics we use for other spurious categories of relation, say, “What is love?” or “What is art?” known in America by performances of shadows that taunt “What is it not?” then cast the body into it

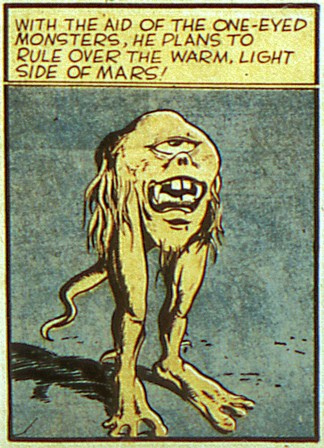

Both words aim to emancipate the other—toward an end of either autonomy or death. As I watch the selection of shorts in Anti-Ethnography—first shown through Cellular Cinema at Bryant Lake Bowl, now out of order on my screen—some of them performance art, others archival footage, others more sensory documentary—a double-vision conjures stunt doubles. I think about what is implied in “anti,” and who the films are for. I determine that “ethnography” refers to the violent visuality of 19th century entertainment schemas of colonial expansion that included minstrelsy, human zoos, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and World’s Fairs, the objectification and taxonomy of natural history, and the science of the museum, which, despite the address and evolution of anthropology itself, continue today in the perceptions and actions of people under the structures that created it—what is it not?

The stunt doubles turn the weaponized camera into an anti-colonial tool for self-representation. The form of my essay stutters along attempting a similar thing: I am using the master’s tools, which means I am calling myself out at the same time I am rubbing the bruises—the need to sound authoritative, to connect the dots logically, to construct an argument that will pose with a stereotypical stoicism in front of my wild interior that experiences in terms of metaphor and thinks in terms of images—the self who moves. In the amount of time a person can spend learning other languages, can a person also come to terms with their own? If so, the more I speak it the more I separate from the person who was conditioned into a common language. I bifurcate; I become contained in my language; I forget the common language and must learn to translate myself into it, which gets old. I notice, instead of trying to understand, people tell me to speak clearly.

Philip Deloria paraphrases D.H. Lawrence in Playing Indian,

“Americans had an awkward tendency to define themselves by what they were not,”

and of “wanting to savor both civilized order and savage freedom at the same time.”

This American identity-making depends on a dialectical oscillation, between is/not, good/evil, for/against, black/white, pro/anti—male/female—so that when there is a glitch—retreading steps—fixating on a gesture—making an artifact out of an image—a momentary slip into one’s native tongue—

The rhythm of what we know to be true (a narrative conclusion)

is disrupted by the attention we give to debris (what doesn’t fit)

I watch the films that glitch along the line between performed and represented, viewer and maker—not as flaws in the Grand Plan, but its canaries in the coal mine.

In the glitch the violence of the Western predi(a)lection for visuality enviscerates

or becomes flesh

While documentary is used to justify, legislate and historicize, art invents a voice for the possible. It asks, backwards, is it future or is it past? For the voices to speak without having to explain themselves, be “informants,” translate traumas for consumption or commodification or for the sake of a unified state requires media expansive enough to translate secrets without betraying them, to love without devouring— media which acts as a decoy.

And say I am not around to direct my double? Who translates then? Anti-Ethnography is built on the idea that “playing Indian” is absurd—that the practice of miming the other is not science, but theater.

A GHOST DANCE on my laptop—Buffalo Bill’s signature in the corner puts a subtle stamp on the performance—meant to put an end to westward expansion

& to drive out whites—by calling up the dead—what did Wovoka wonder I wonder—when the power of dance was invoked only to be rebranded—& trauma immortalized for its on-screen presence?— a glitch implies repetition, scarring, woe potential—

Or stuckness—the film is a container for what (I) a body cannot hold

it—a glitch—holds what—(I) a body—holds—bones—

belonging to it—(I) the film—remembers for it—(I) a body—what it’s owed—(I) a secret—belonging to it—a backward expanse—out of the museum (I)—out of curio cabinets & World’s Fairs—out of the earth full of pipelines—& cities full of workers—

However, the archival footage of the ghost dance now takes on a different power—the film immortalizes the dance & the glitch repeats its gesture—so it is not trauma, but the dance itself which casts its spell, invoked by pressing play—

A stunt double secret: calling up the dead to drive out the other which has murdered you is a long process, and it hasn’t been that long—

A secret, reiterated by Pedro Neves Marques in “LOOK ABOVE, THE SKY IS FALLING: HUMANITY BEFORE AND AFTER THE END OF THE WORLD”:

“The world has already ended…”

In the (re)writing or (re)winding, instead of the camera being weaponized to taxonomize the vanishing, the ghosts return—the ghosts carry on dancing, the ghost/glitch drives out what is ongoing and violent about land divided up in squares and priced accordingly for “resource management” which threatens the immaterial & sacred—including our abilities to care, to remember, to refuse—

The ghosts possess the living, the dispossessed, the possessors—a film is a body of ghosts and glitches—A refusal to be complicit in the gesture—

Like a monologue stopped mid-sentence—like, of course, a machinic glitch in the film, or, when things get weird, a desire to look away—

In one of the series’ more complicated shorts, Revolución: Este es mi Reino,

a man dressed as a classic anthropologist—white, male, wearing a white kaftan, small-brimmed straw hat and aviator sunglasses—speaks of the landscape in terms of the landscape seen by Hernan Cortés, “when he conquered the region”—

Curated snippets of conversation indicate narrative outside of or inscribed in its spaces

Aunts discuss maps, a child should know his own country first, before he knows Europe or the Americas

The camera wanders around not unlike an anthropologist

While music, like high school pep band music, surges, the scenes begin to glitch along with people’s drunkenness—as the scene turns to chaos, the glitches increase—a bench is thrown through a car window: “No es Canada!” shouted by some off-screen adults; another glitch catches a conversation, “quien trajo el Argentino?” as a child smashes a rock in the window of this car—

A bougie-looking couple makes a plea for pulque, a ritual drink thought to contain the blood of Mayahuel and Mixcoatl but which became desacralized during the colonial period

The camera follows an old man whose hands scratch around in his pants as he describes which newspapers he’s affiliated with

A white woman with an gringo accent says “They don’t need this disorder! They need order!”

Various people quoted saying la policia no hacen nada

A woman running away from a scene shouting lo esta matando! lo esta matando!

Then off in the margin, three men, in silence, watching, maybe, one holds a child

While behind the cameraman, in front of them

A car is on fire; the film ends in rainbow-colored letters that say “ESTE ES MI REINO”

This is my kingdom

I finish the film, at once cinema verite and highly edited and I am troubled—I am not sure if it is the film’s material, the editing or what I’ve written about it that troubles me—but then I think—if I am troubled by what I can’t find language for, it is not the glitch I am worried about—I am worried if it is me who is the glitch, because I am the thing that is not supposed to be there.

Davi Kopenawa, Yanomami shaman, calls white people’s writing “image-skins,” which they need to hold their memories, because they don’t know how to hold them in their bodies—I write a second body as I think about memory, secrets, and the uniterable. Its filminess I suppose is a kind of texture for the skin. Filmy means thin or translucent, like paper. Does it hold a visage? If I don’t aim to make a “subject,” follow it to its end? Is film a kind of writing, or is writing a kind of person?

What do they hold in their skins, and is it different—? This is the ethnographic question.

If it is different, is one better than the other—? This is the technological question.

If one is better, does it make sense to keep the other—? This is the question of museums and genocide.

In The Violence of a Civilization Without Secrets, Adam and Zack Khalil follow “The Kennewick Man,” the excavation and controversy surrounding a ancient skeleton found in Kennewick, Washington, whose cranial shape, according to some forensicists, seemed to indicate European origin. Because the bones’ age could not be determined, white supremacists co-opted the story to justify European ancestry in the Americas.

During the controversy over repatriation rights per NAGPRA jurisdiction, settler indignation over a “right to stay” and questions of what to do with the bones, the court was unwilling to accept an oral history that verified the indigeneity of “The Ancient One.”

This is the difference between knowledge in service to historical materialism—evidence—and knowledge as testimony—embodied. It was not until 2014, when new technologies for Ancient DNA testing made it possible to verify who the bones “belonged” to, that The Ancient One was returned. He was reburied in a secret location on tribal lands in 2017.

Am I a liar? you asked me as I recalled, then named each instance over the past year in which you said this but not that and what this meant when you refused to be that

because you’d said I was forgetting the temporality of this and not that, that this was true in that time but now, since the feeling changed, was not

But I have screenshots! I said, I don’t think anyone is a liar, then, if they only mean what they mean at the moment they say it

If even a treaty is conditional, how is anything true?

A post-truth, post-fact, archived-by-the-minute context for truth meant, to me, that all my dreams of alligators were real

Whether they held up the world on their backs

While the sky fell down on them

Whether I canoed through the mangrove as they snapped up at me

Or I stuck a branch in its jaws in order to move past it without being eaten

No one is a liar as I become the animal who eats the other because this is what it does

“in a state of primordial cannibalism…when everything was human”

Because I don’t know how to hold the memory in my body I purge it onto the page

Writing what is held in my body

Creating a clone for everything I can’t digest / museum of bones

I could not grind into an ash and drink

In The Laughing Alligator the glitch repeats laughter, chants, gestures—the glitch fixates, obsesses on moments & images

I obsess that my chosen medium rotates on an axis

Of keeping my subject alive long enough to finish it, killing it, for fun

The way, in love, I fixate on moments that verify that my love happened or this love is not real or when they said this but not that and what this meant in a refusal to be that

There’s a joke Vine DeLoria, Jr. (Sioux) relates in Indian Humor:

“It seemed that a white man was introduced to an old chief in New York City. Taking a liking to the old man, the white man invited him to dinner. The old chief hadn’t eaten a good steak in a long time and eagerly accepted. He finished one steak in no time and still looked hungry. So the white man offered to buy him another steak.

As they were waiting for the steak, the white man said, “Chief, I sure wish I had your appetite.”

“I don’t doubt it white man,” the chief said, “You took my land, you took my mountains and streams, you took my salmon and my buffalo. You took everything I had except my appetite and now you want that. Aren’t you ever going to be satisfied?”

Or just not hungry anymore. I said I write what my body can’t hold—more likely I write my body—or write to understand what I don’t know—I write to take the place of eating

When the condition for eating is toxic—when I eat I ask myself is this love or am I dying?

The ethnographic encounter, like love or living, has to do with desires to devour,

a willingness or refusal to be devoured—

As if by consenting to be eaten, you might save yourself from hunger

To become hostage to the camera, “a warning”

On the inarticulate plane;

In 1976, Juan Downey spends 7 or 8 months in the Amazon with the Yanomami because he “wants to be eaten up” by them

He describes the practice of eating their dead as “not cannibals, because they eat their dead in order to keep the beloved immortal”

Like a film or a poem, turning the bones to ash & mixing the ash with beer

A Yanomami told Juan once that “he loved me so much, he wanted to eat me up if I died of malaria…was it true love? Was this the ultimate funerary architecture?”

& Juan said when he died he wanted his body to be drunk this way~~~~to become the other, truly, running through the blood

The way Monique Wittig describes, over 163 pages, an erotic ethics as “unpeeling your skin, layer by layer…m/y delectable one I set about eating you, m/y tongue moistens the helix of your ear delicately gliding around, m/y tongue inserts itself in the auricle, it touches the antihelix, m/y teeth seek the lobe, they begin to gnaw at it, m/y tongue gets into your ear canal. I spit, I fill you with saliva.”

Love is a cannibalistic gesture

One desires to unzip skin and slip inside

It’s a little gross, describing love as peeling apart the body that contains it—

As it is gross to think of the ethnographic as an exotic/erotic pedestal for the Other~~~the always-already gendered, sexualized, racialized Other, a body double

As it may disgust to listen to serial killers describe murder as intimate acts

But isn’t love mostly torture—?

Anti is a kind of love that keeps its prey alive

An alligator swims through reeds muddied by a lie built from the assumption of clear water;

The secret held by this assumption is that I don’t know whether I am calling up the dead or driving them away

I toss my line in anyway;

The line is imperceptible from here but I know a line in water displaces the line

To appear broken; say, in a glass. I double, becoming a clone of myself

to inhabit the space between what I know to be true and the glitch that breaks the line

As I triangulate it from myself in the canoe to the gator in the reeds

Now, bifurcated, I can instruct the clone to speak for me when I am tired, I can rely on it to rewind and replay when I get sick of amniosis, a skin to puncture

So that when the gator swims toward me I will not be devoured

As I write is this love or am I dying?

This article was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Jordan Rosenow.