Adu Gindy : Several Thresholds

Adu Gindy's paintings are featured at three galleries in Duluth this month: the Duluth Art Institute, Waters of Superior, and Pizza Luce. Differing bodies of work are shown in each place. How does context affect artwork?

It’s not often you can see the work of one artist in three places at once. A pizza joint, a nonprofit exhibition space, and a commercial gallery are all exhibiting the work of Adu Gindy, a strong and well-respected painter from Duluth. I got interested in what bodies of work the different venues elicited, and how the spaces inflected the experience of the work.

Gindy is prolific; any given body of work can consist of hundreds of pieces. Certain practices–drawing in paint, working out variations in imagery and color on paper, then moving onto large canvases–form these various groupings.

As you might expect, the most challenging work is shown in the big gallery of the nonprofit space, the Duluth Art Institute. Big spare canvasses, lots of cloth showing, bubbles of stain-thin paint in pure colors, an occasional photo clipped from a magazine, roughly, stuck into one or two of these colored bubbles . . . these aren’t artful. They’re a bit stern, and assume a viewer’s knowledge of the artist’s prior work, which was far more composed, more rhythmic, more lyrical. These new things use the gap between the richly layered and indulgently generous earlier work and the spare perfunctoriness of these works as a resonator, a hollow space that inflects your experience of the paintings.

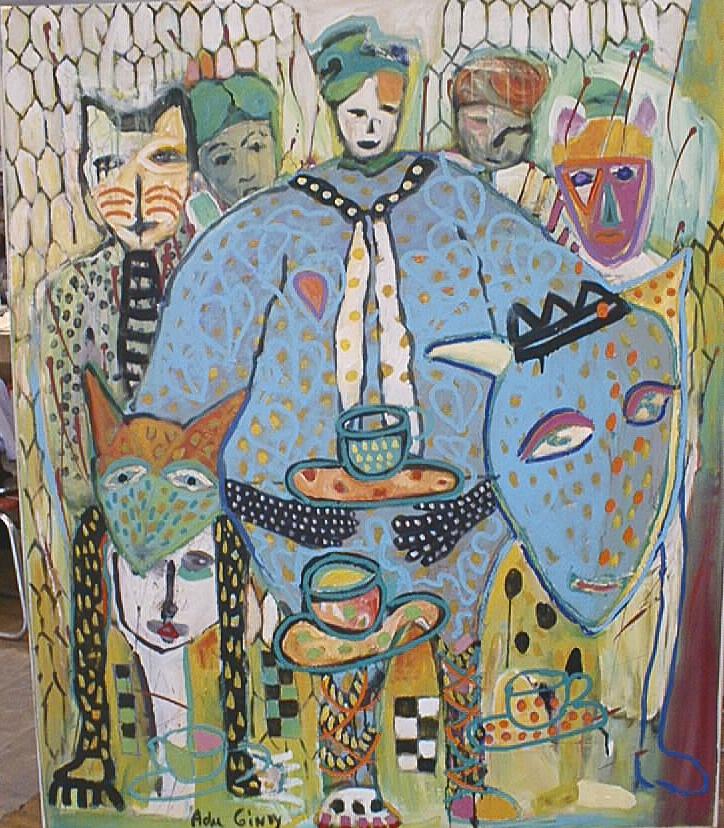

The hollow, says the artist, or the gap, the distance, was made in part by 9/11. Pushed away from lyricism and engagement by the raw loss pictured on a million TVs, Gindy peeled her process down to mere making, mark-making, and seeing and seizing images. And it’s images of the nonhuman world, largely, that are chosen from the magazines, edged by images of humans exhibiting the behaviors that tie us to the world of animate, animal life. It’s the seam between the animal and the human that appears here, apparently because, for this woman who has lived over half a century, the human world has proved in the course of recent events to be profoundly disappointing.

Oddly, ornament serves as one of the strong themes of this austere and demanding work. A frequent image in the roughly clipped roster of magazine pictures is a wild cat: a tiger, a leopard, a lavishly ornamented creature. Also pictured are quetzal birds, colorful primates, other highly ornamented creatures. Along with these are ornamented humans, people with body paint, makeup,or clothing that makes them resemble these exotic creatures. Gindy has noted that in this work she’s looking for portals into the shared world of animal and human doing, making; she sees realization of the animal nature of the race as a kind of redemption or a route to some saving grace.

Another large group of works in this gallery is a field of small works on paper, the traces of a daily practice of imagemaking from which rise the larger themes of the big paintings. The field of images here is a field of incident, of the incidental: small color fields emblazoned with cutout images. The dominant theme is Egypt, coffins, the seam between the living and the dead , a world for the dead that is attended by the living.

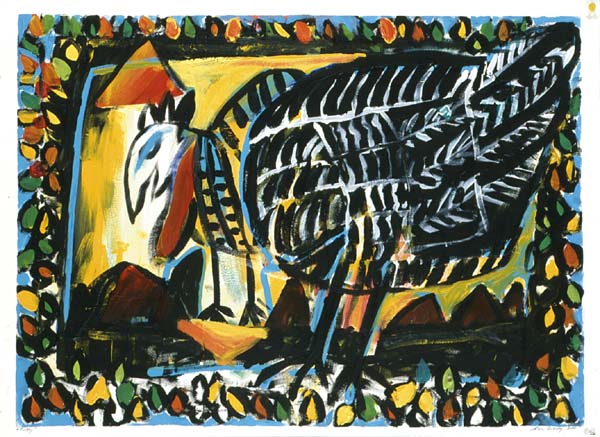

A similar wall of small works is in the Waters of Superior show as well. But the Waters show also features more painterly works from the “Sky Is Falling / Chicken Little” series, only a few of which were at the DAI. An especially strong group, with imagery of chickens, soccer balls, dancing rabbits, all on black backgrounds, held another wall, while lyrically joyous work, probably done a few years previous, faced them across the room. Gindy describes the “Sky Is Falling” group as being, really, about mercy. Her artist statement says:

“The . . . canvases are my response to a particular story I heard about the last-ditch efforts of victims trapped in the tower who chose to jump instead of being burned alive. One specific account touched me deeply. A witness saw some people flapping their arms in an effort to fly as they jumped from the burning towers. I thought, If only they had wings or could bounce like balls, or if they had a big safety net to catch them, they would have lived. The bouncing balls and cavorting rabbits amid the churning almost transparent atmosphere pay tribute to the victims, and also to the ever-optimistic side of the human spirit.”

To go from here to Pizza Luce: this room is devoted to Lord Gut,and here people drink, dance, and eat good rich food— all activities of which the artist would approve. The work shown here is sybaritic, lovely, layered with the rhythmic line and resonant coloration that Gindy is primarily known for. Her work has in the past been deeply sensual, joyful, playful: and here in the cavernous dark reaches of a room where people are already soaking up sensation, these works act like teachers of sensuality done right. Unfortunately they may not be heard above the noise.

And how does it all play out to the watchers, the possible buyers, those whose desire creates the market? Well, not as you’d expect, maybe. Sales at all three venues are very similar: a couple of paintings at each. Perhaps, no matter the context, art is spectacle rather than product nowadays—or maybe, as with every other realm of our lives in the annus horribilis of tax cuts and deficits, “it’s the economy, stupid.”

The shows:

The Duluth Art Institute: through July 6, in George Morrison Gallery in the Depot, 506 W. Michigan Street, Duluth

Waters of Superior: through June 24, 395 Lake Avenue, Duluth

Pizza Luce: 11 E. Superior St., Duluth