Ache with Many

On A Feather Plucked from Its Bird—Benjamin Merritt's exhibition at Dreamsong—printmaking as metaphor for healing, and the uncontainable vastness of illness

1. In philosophy, pain is a feather plucked from its bird.

2. In literature, pain is an index separated from its book.

3. In movies, pain is a tree, but never its ax.

Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, vulnerability, mortality, medicine, art, time, dreams, data, exhaustion, cancer, and care1

Benjamin Merritt’s solo exhibition at Dreamsong, A Feather Plucked from Its Bird, is dually titled after a quote from Anne Boyer’s The Undying and Merritt’s eponymous unbound artist book, which is a centerpiece to the show. In an Instagram post promoting the opening of the show, Merritt states, “I love the phrase because it puts the emphasis on the feather ripped from the bird, but also emphasizes the importance of the multiplicity of the feather compared to the singularity of the whole. My love for print is the love for those of us who are large in number but have been overshadowed; all the invisible illnesses, the constant tiny battles, that become visible in number. I hope this show makes people feel more visible.” This sentiment is felt deeply in the atmosphere of the gallery, and in my time spent encompassed by Merritt’s work.

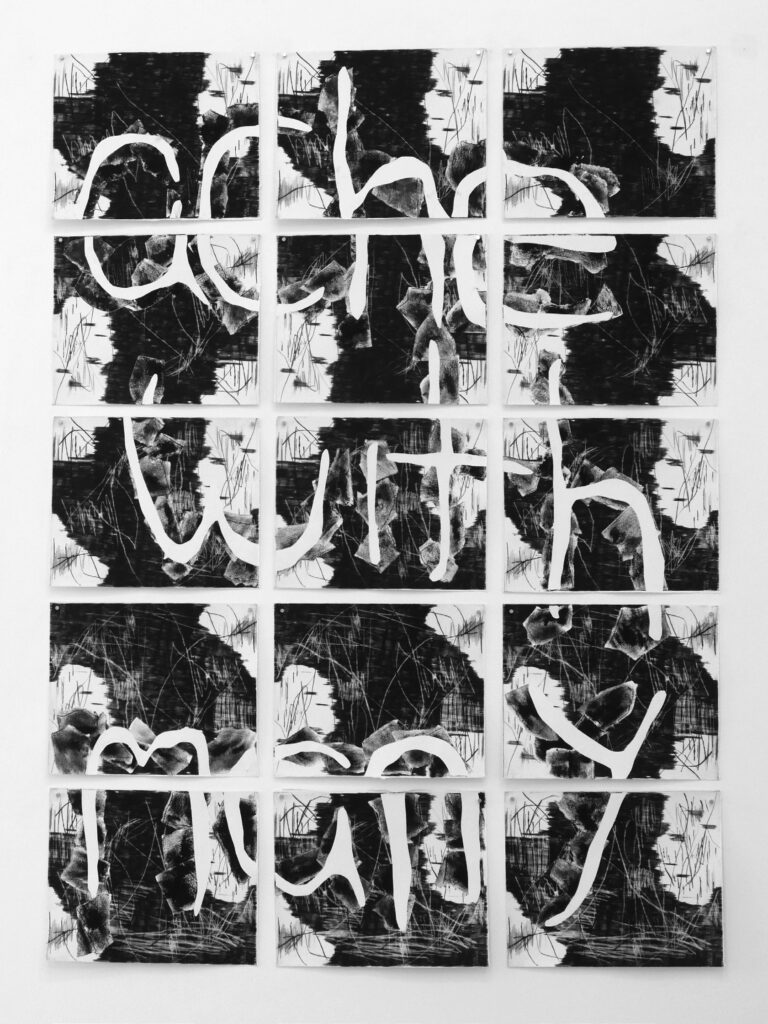

Walking into the gallery, which is located in the second room of Dreamsong, I take in the show all at once, like unfocused eyes gazing at fireworks. I see remnants of illness even without the focus needed to digest the statements each print holds. The amorphous, organic, black and gray shapes that texture the prints remind me of blood and iodine-stained bandages. I am transported into my grandmother’s bedroom, where I kneel on the carpet, wrapping her legs and feet. I remember the wounds that refused to heal. Turning to my left, I back up to take in Among The Wildflowers, a formation of several prints with large, interrupted, white letters that read: “ache with many.” An incomplete statement, created with a large handwritten type, cut out and placed onto the prints. The statement feels complete but expansive to my sick body, to the memory of my grandma, to the title of the show—a reminder of community, of the many.

The exaggerated handwritten type is featured throughout the show, a byproduct of painting letters backwards for printing. It reminds me of my own uneven, dyslexic handwriting—and the pencils I snapped as a child from gripping them too tightly in an attempt to write evenly. The lettering, undeniably a product of bodily labor, contributes to the weight of the prose, much of which references pain and illness. Every element of Merritt’s work feels considered. Simultaneously, there remains an urgency to all of it. In a press release for the show, Merritt states, “The print is a metaphor for continual healing, it’s morphing physicality a reflection of the body.” The careful, repetitive, and experimental printmaking process is a particularly apt metaphor for attempting to heal while having a chronic illness: repetitive, taxing motions of searching for answers, with the long, simmering urgency of an almost unlivable body. The ghosts of past prints featured in much of the work in A Feather Plucked from its Bird are reminders of unfinished histories, but also a desperation and rashness built from unrelenting pain.

“A widely held notion about pain seems to be that it ‘destroys language.’ But pain doesn’t destroy language: it changes it.”

Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, vulnerability, mortality, medicine, art, time, dreams, data, exhaustion, cancer, and care2

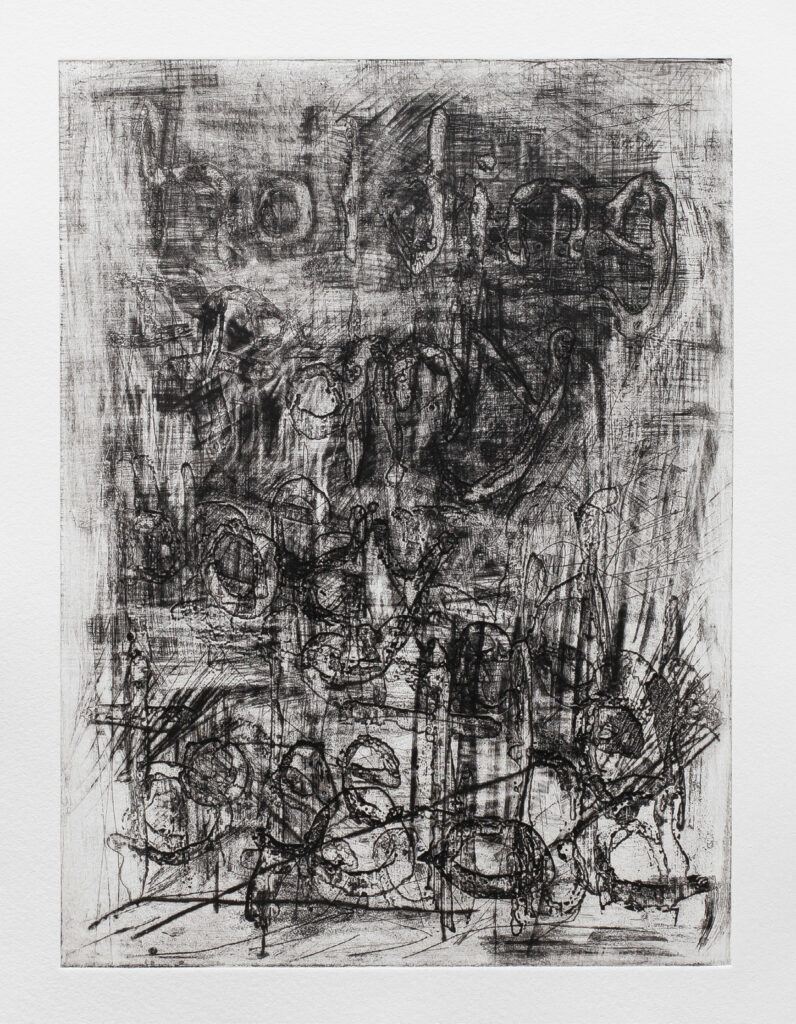

I spent a long time standing in front of the prints from Merritt’s unbound artist book—which are presented hung on the wall, as well as in a handmade box on a table in the center of the gallery. I stood long enough to feel the pain in my knees and hips climb to my arms and scalp. In some of the prints, the text is almost completely unintelligible, the already exaggerated and crooked hand-painted text covered by the ghosts of past prints and what feels like a million little scratches. Two prints in particular are shrouded by marks, A Feather Plucked from Its Bird (6) and A Feather Plucked from Its Bird (20). My time spent with the prints is eventually rewarded by the revealed two statements: “nothing reveals itself to me” and “holding my body together.” These statements represent the “reward” of the labors of illness—nothing definitive, nothing clear, a sea of murky untested medicines, life hacks, and misdiagnoses. The reward for swallowing this murky water, again and again, is a body being held together just enough to continue forward, or at least stand still.

Benjamin Merritt, A Feather Plucked From Its Bird (6), 2022. Photo courtesy Dreamsong.

Benjamin Merritt, A Feather Plucked From Its Bird (20), 2022. Photo courtesy Dreamsong.

“The last needle wiggles into my arm, I hold my breath, and they swim it around like a child’s hand reaching under the bed, the needle is plucked from my arm as if I were the bird and the needle were everlasting pain itself, I lean forward and nothing reveals itself to me, I feel my body in bitter triumph proving that I won’t control it:

I told you so.”

Benjamin Merritt, excerpt from Pain is a Feather Plucked from Its Bird

“Imagine for a moment

I can apologize to my body.

I will learn to show affection

for the dried blood

holding my body together,

all of the labor, all its selfless work.”

Benjamin Merritt, excerpt from My Mom Tells Me Not To Pick at My Skin

This is language transformed by pain. This is language that makes seen the unseen realities of chronic illness.

“A problem with a sick bed scene as painted by the sick person herself is that it would have to be painted on a canvas with no edges, to be too small to measure, to be too large to contain. It would happen outside of time, happen inside of history, exempt the present from the linear, rearrange substance so that blankness is an element, rearrange aesthetics so that the negative is almost all.”

Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, vulnerability, mortality, medicine, art, time, dreams, data, exhaustion, cancer, and care3

The clean, unmarked borders of Merritt’s prints provide a harsh container for the bleeding prints. This severing of textured shades of gray by the simple white paper serves as a reminder of the uncontainable vastness of illness. The statements hung on the wall from the artist book are broken and interrupted, sampled from multiple poems which are dispersed throughout the stack of unbound prints and held by an open box on a table in the center of the room.

When I slipped on the white cloth gloves left on the table and held the first page of the book, I was startled by the weight of the paper. Having spent so much time gazing at the prints hung on the wall, feeling largely only the physical weight and pain of my own body, holding the thick paper of the prints becomes yet another reminder of the “many.” The poems featured in A Feather Plucked from Its Bird capture the multiplicity of chronic illness. There are moments of heightened specificity, like where Merritt describes his couch: “little specks of fried rice visible in the crease, my cat stained the off-white cover with kitty drool,” and writes about punk music and mosh pits. These are the details that fill the vastness of illness, as much as the grief, blood, and specific symptoms. They are tools of survival. They are reasons to “never forgive those who think being sick makes us weak.”

In the spirit of vastness, “the many” and what is uncontainable, this review hardly scratches the surface of the deep wealth of crip wisdom present in Benjamin Merritt’s A Feather Plucked From Its Bird.4 This monumental exhibit can only be fully appreciated when given ample time and space to take everything in. Merritt, and Dreamsong, are providing a space of disruption and visibility in a time where many sick and disabled folks feel cast aside or unseen. May this show be a reminder that in a world saturated in illness and grief, disabled voices will undoubtedly lead us forward.

A Feather Plucked from Its Bird is on view at Dreamsong January 29-March 12, 2022. More information at dreamsong.art.