Freedom in Discipline

Camille LeFevre reports back on the Guggenheim's retrospective exhibition of work by noted abstract painter Agnes Martin, whose restraint and discipline on the canvas offer a much-needed respite in turbulent times.

“To be abstracted is to be at some distance from the material world. It is a form of local exaltation but also, sometimes, of disorientation, even disturbance. Art at its most powerful can induce such a state, art without literal content perhaps most potently. Agnes Martin, one of the most esteemed abstract painters of the second half of the twentieth century, expressed—and, at times, dwelled in—the most extreme forms of abstraction: pure, silencing, enveloping, and upending.”

Nancy Princenthal, from Agnes Martin: Her Life and Work

Dismay. Illumination. Uplift. Irritation. During and after a day spent viewing the first New York retrospective of Agnes Martin’s work, at the Guggenheim through January 11, all of these sensations arose. In the Guggenheim’s white rotunda, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright to spiral up, seashell-like, through six levels—with a vertigo-inducing atrium open in the middle—Martin’s equally austere works are hung in rooms and alcoves along the gradually elevating (or declining, depending on your direction) ramps.

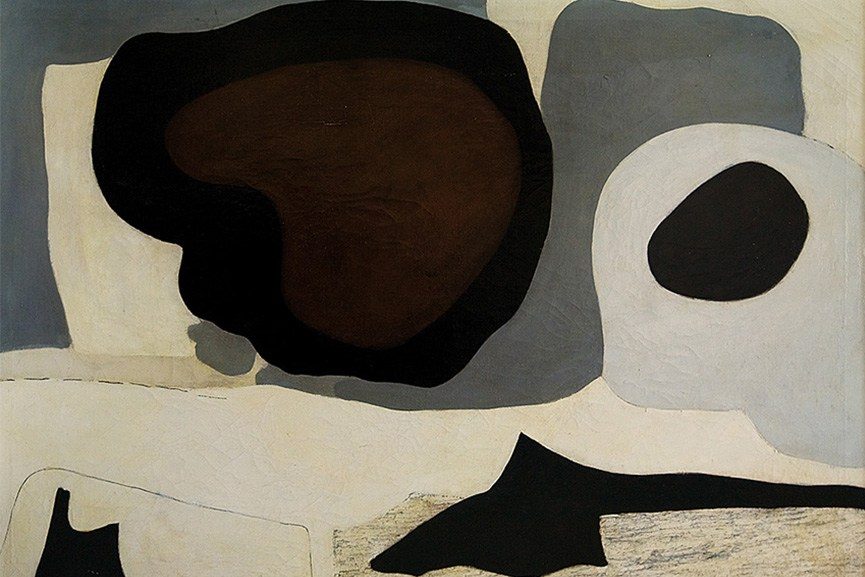

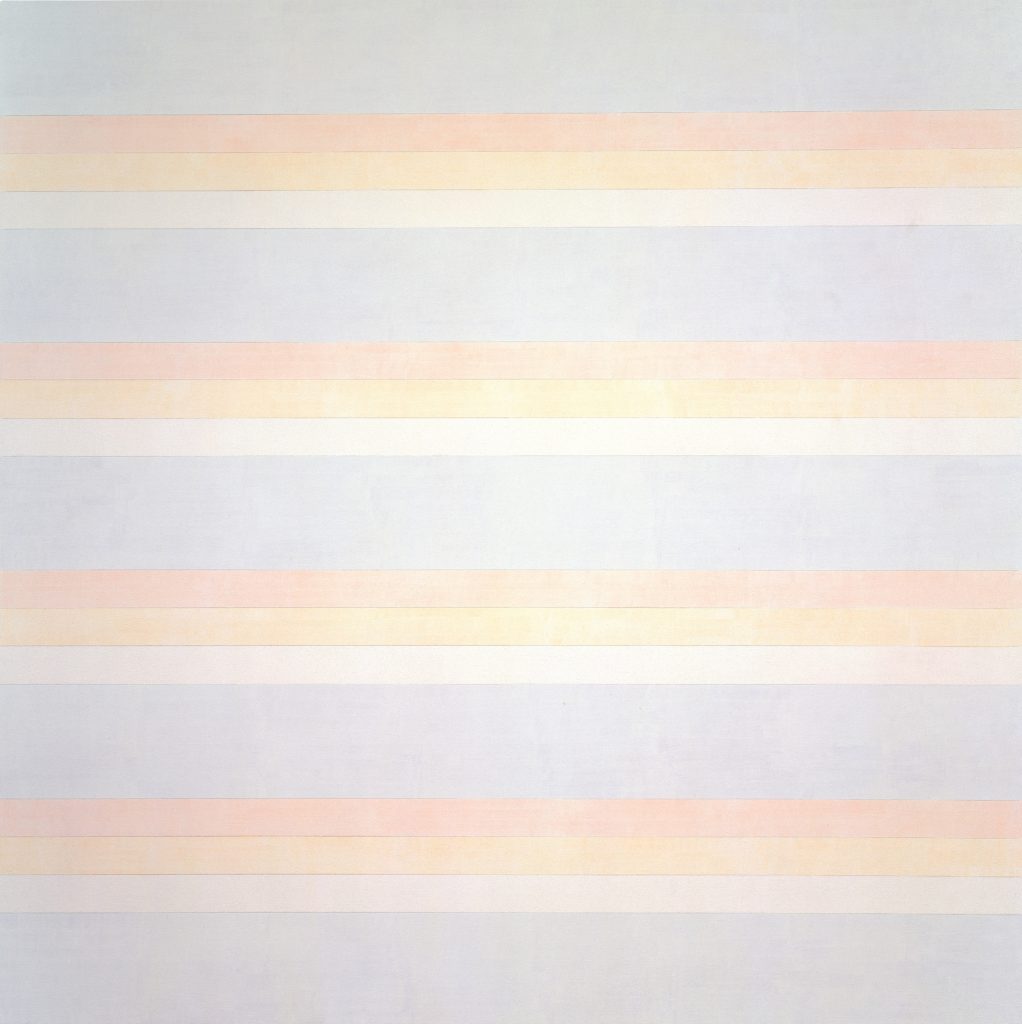

And the exhibition opens with a challenge: How did Martin (1912-2004) get from here—Mid-Winter (1954), an oil on canvas bursting with large bulbous forms hugged by curving shapes underscored with horizontal fragments all in a color palette of black, brown, grey and whites—to there, an entire room devoted to the 12 nearly-white line paintings that make up The Islands (1979)? The latter are large-scale works of respite and luminosity; classic examples of Martin’s horizontal grid paintings rendered with such a refined hand and disciplined sensibility to render the descriptor “minimalism” almost moot .

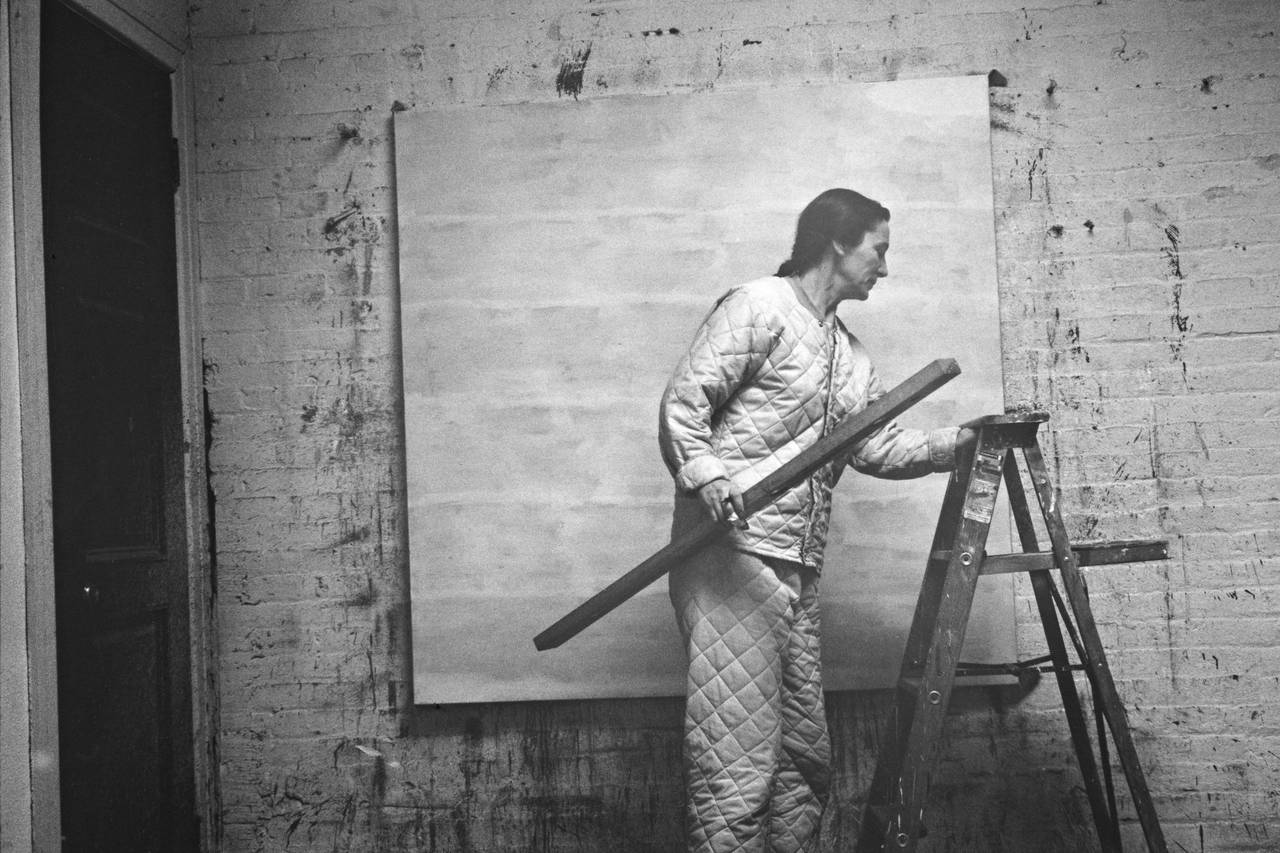

Martin famously (and infamously) destroyed nearly all of her paintings before Mid-Winter. So, the process of moving through the exhibition, of circling up through the Guggenheim and viewing the work, which is largely organized chronologically (with a few jarring exceptions), is to experience the ardent refinement of a life, aesthetic sensibility, and artistic practice to its exquisite apex. To achieve this, Martin lived an ascetic life, punctuated by moves (she eventually settled in Taos, New Mexico), bouts of and hospitalization for schizophrenia, a few well-guarded love affairs, exhibitions, fast and expensive cars, and travel.

But toward the end of her life, after moving from the house and studio she built in the high desert to a retirement home (she’d leave every day, driving to her studio to paint), which took care of her cooking and cleaning needs (although, in a video at the Guggenheim she mentions giving up housework long before that), she was free to devote herself solely to painting. Free to heed the “visions” that provided the “inspirations” (Martin’s words) that she reproduced as her work.

While one wants to shake Martin for her refusal to engage, doesn’t her work also represent a much-needed respite from the crudity and cruelty of 21st century politics?

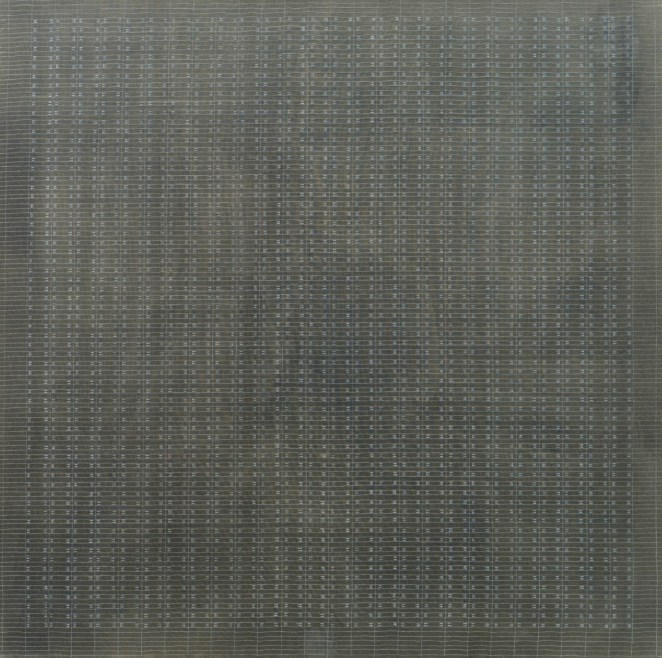

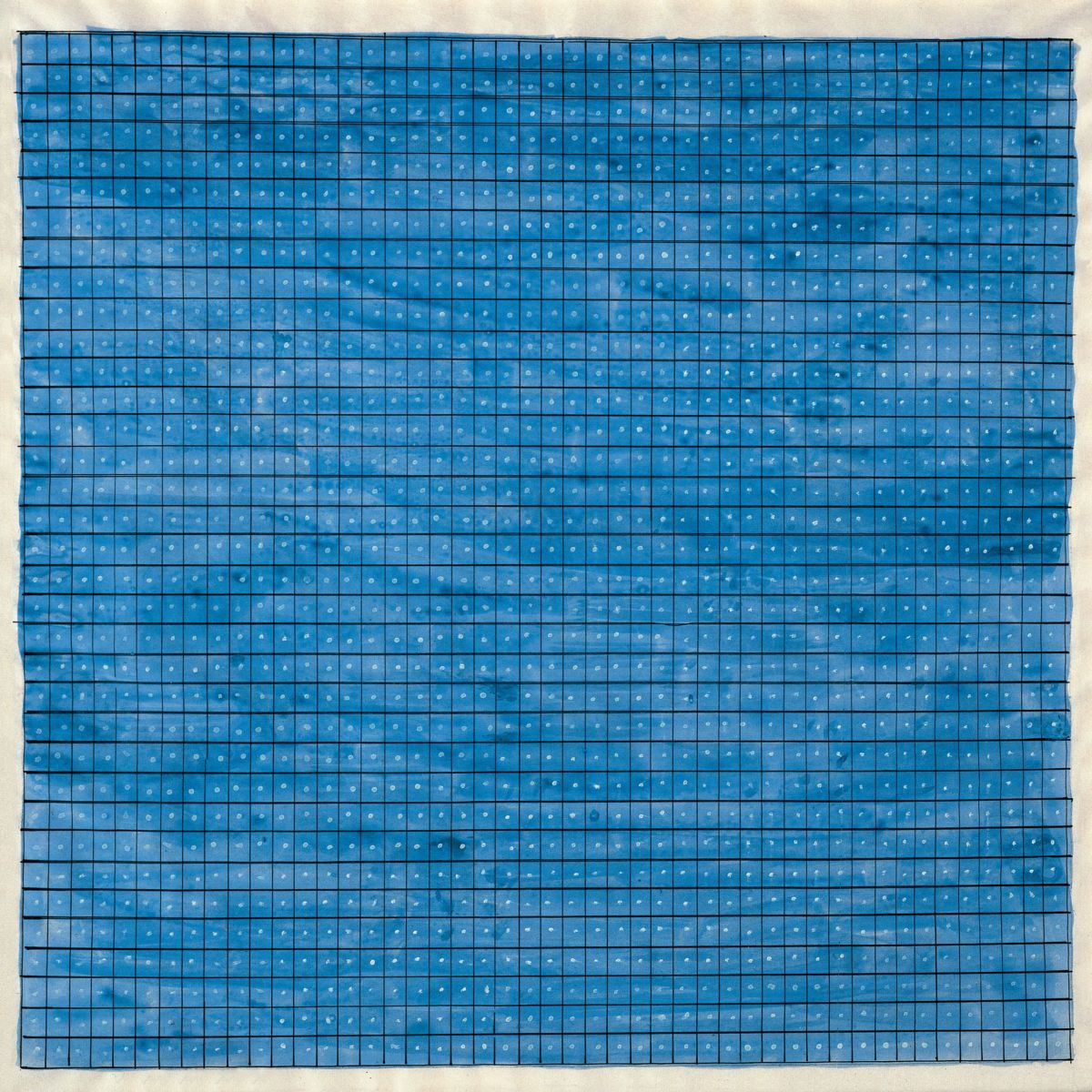

Grids. Dots. Ruled lines. When Martin finally lit on this painstaking system of making work—of, dare we say, organizing her prodigious thoughts and roiling emotions in a way that offered a sense of control—she was on her way. White Flower (1960-62), made while she lived in Coenties Slip (a warehouse area near Wall Street in New York) resembles a brown piece of cloth knit with lightly dabbed flecks of white in a perfect grid. The work appears at once archetypal and ahistorical. Keep looking. With White Flower and many of the works that follow, distinct tonalities and shapes start to emerge.

So, too, does a sense of movement—in the washes, such as Summer, 1964, in particular. Martin’s fine lines (drawn with graphite and using a ruler) in her precise grids issue order and restraint, while also giving the work an extreme formality that safely contains the embedded diaphanous forms, textural materiality, and painterly sense of movement that morph to the surface of those grids. For Martin, in other words, discipline was freedom.

In their extremity, however, Martin’s paintings illustrate just how well she was able to turn her back on the world (a film about her, With My Back to the World, shares this sentiment). She chose a life of solitude. And in works such as White Flower II and Fiesta (both from 1985), Martin reduced her palette to gray and white, with horizontal lines as defined as those printed in a notebook. In her biography of Martin, Nancy Princenthal says such works served to guard Martin “against the vulgarities of life.” Martin’s work, she adds, “not only challenged the visual and psychic abundance of the world but also filters it, relieves it of impurities.”

Martin studied Zen and Buddhism. She believed artists shouldn’t be of the world and should avoid political and social responsibilities. Here’s where the irritation enters in. In one of the restrooms at the Guggenheim, just beyond Martin’s work in the rotunda, is Maurizio Cattelan’s America, an 18-karat gold toilet that’s heavily guarded but free to use. Ostensibly, the work was created to give anyone (who had paid museum admission) the opportunity to experience a luxury enjoyed by the 1 percent. Instead, it’s something of a horror.

In our current political climate, evoking the lifestyle of the President-Elect, along with the narcissism, grandiosity, racism, misogyny, and elitism the supposedly “populist” non-politician represents, Cattelan’s work is a one-dimensional vulgarity. Within the context of the Martin exhibition, the toilet’s expression of intimacy (the seat is very cold, by the way) is anachronistic, if not utterly graceless. But it also sits in stark juxtaposition to the creative impulse and intent of Martin’s ethereal paintings.

While one wants to shake Martin for her refusal to engage, doesn’t her work also represent a much-needed respite from the crudity and cruelty of 21st century politics? And isn’t the idea of a reclusive, creative life attractive, especially now? Martin worked up until her death, creating light-filled color fields with titles like Gratitude and Happiness. She was a tough cookie and an inimitable presence, as well as fiercely protective of herself and her work. But she also exudes, in these last works, a softness that’s as much a refutation as an embrace.

Agnes Martin is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City from October 7, 2016 – January 11, 2017.