A Man Apart

Choreographer and dance writer Linda Shapiro studied at the Merce Cunningham Dance studio in the '60s and offers insights here about what it is to dance "inside the maelstrom" of his movements, sharing her experiences of him as both teacher and artist.

WHEN MERCE CUNNINGHAM DIED THERE WAS NO ONE LEFT to observe the world in quite his way. Like a biologist or physicist, he looked into the wilderness of forces and organisms and random collisions that constitute our universe. He never lost faith in Man and Woman as finite creatures with infinite possibilities, and so he harvested those elemental urges for every gesture — warm and cold, big and small, dry and juicy — that a warm-blooded creature could manage. And some they couldn’t. “I am no more philosophical than my legs,” he claimed, and he meant it. There was no hitching his wagon to some starry theme or gnarled narrative of War and Peace, Love and Death. He just let the body’s movement have its head, allowed the common pool of motor impulses we all paddle around in to suffer a sea change into something rich and strange.

In the 1960s, I was an English teacher living in New York when I first saw the Merce Cunningham Dance Company perform. I had no words at the time to describe the deep sense of connection I felt with this abstract, uncluttered, rhythmically unscannable movement. Cunningham’s work had the look and feel of ballet, which I had studied: the elongated line, the buoyant uprightness, the complex and highly articulated footwork were all familiar. But Cunningham’s twists and torques, his off-balance shifts and stutters, the plainspoken delivery he demanded (no attitude or emotional tone layered on top of these moves) were new and energizing to me.

So, I went straight to the Cunningham studio and stood in the back of the class for the first three years, hacking away at the complex coordinations, the rhythmic subtleties, the feats of strength, balance, and endurance it took just to get through a 90-minute session.

In class, as we moved repeatedly across the floor attempting one of Cunningham’s phrases, I found myself sucked into a vortex that spewed me out, frustrated or enlightened, at the other end of the studio. The panting, gasping, cunning animal in me was simultaneously released, and then relinquished, in favor of something even more intoxicating: a sense of myself as part of an intense communal momentum, everyone pushing their limits, as if dancing on the edge of a precipice. Over and over, in his classes and those of others who taught there, I experienced movement as a jolt of awareness that engaged every part of me and focused (or re-focused) my being. It is this more than the technique or aesthetic philosophy of Cunningham’s work that has most directly influenced me as a dancer and choreographer — and as a human being living in a complex world.

“A man is a two-legged creature more basically and more intimately than he is anything else,” Cunningham wrote in a 1955 essay The Impermanent Art:

And his legs speak more than they ‘know’ — and so does all nature….So if you really dance — your body that is, and not your mind’s enforcement — the manifestation of the spirit through your torso and your limbs will inevitably take on the shape of life.

Cunningham and his work have shaped my life in myriad, often unexpected ways. During the seven years I studied there, I had no desire to dance professionally, or to make dances (both of which I wound up doing later). The only thing I wanted was to participate in what I thought of as subsistence level dance survival. Something in my rather lazy, certainly scattered intellect stood at attention, collected itself, and pushed ahead while I danced at his studio, three or four times a week. Those classes became rituals that helped me to cope with the random chaos of living in New York and, yes, of teaching junior high school.

Douglas Dunn, a member of Merce’s company from 1968-73, describes an, as he puts it, “overtly inflamed” Cunningham teaching a class:

Late in the class he presents a phrase that goes speeding down the length of the space in collision course with the mirror, and, in a last-second, explosive and indecipherable complication, careens to the floor. He shows the phrase over and over, not counting but singing. He seems not to be teaching, just doing, just dancing. The wildness is riveting, but imitation strikes me as dangerous. At risk of compromising my reputation for lack of caution, I call from the back of the room, ‘Could we try it more slowly?’ ‘No,’ he yells, with vehemence, and throws himself again into the sequence like a Kamikaze.

Despite the maelstrom of physical sensations and information, there was also an aura of calmness and sanity about the Cunningham studio, a decrepit space several flights up some rickety stairs. This was before the school and company moved to state-of-the-art digs in Westbeth, a huge studio where late afternoon classes were bathed in sunsets from the Hudson River. At the Third Avenue facility, classes took place in claustrophobically small studios with uneven floors and tiny, rather fetid dressing rooms, which forced a kind of intimacy between students and company members.

______________________________________________________

The panting, gasping, cunning animal in me was simultaneously released, and then relinquished, in favor of something even more intoxicating: a sense of myself as part of an intense communal momentum, everyone pushing their limits, as if dancing on the edge of a precipice.

______________________________________________________

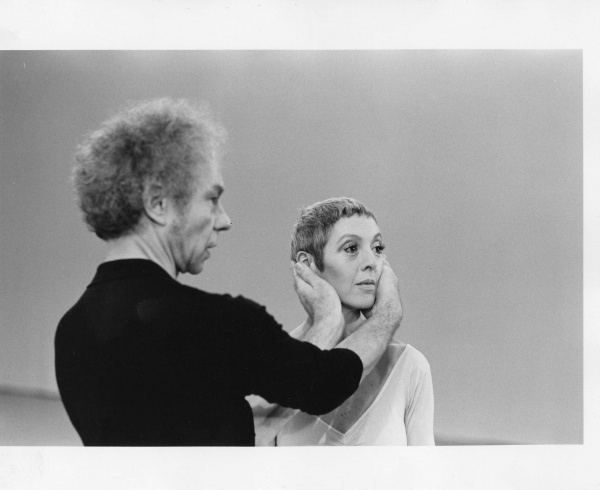

Cunningham himself often sat in the small reception area chatting, or watching the activity around him, or attending to the clutter of plants lining the sooty, barred windows. We often crowded into a small hallway to watch Cunningham teach the company class, where he would sketch familiar exercises with elegant hieroglyphics. He would count as he demonstrated, crooning the numbers in a calm, methodical chant, or illustrate a point with soft-spoken allusions to everything from computer science to Alice in Wonderland (“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”)

Since his death in 2009, Cunningham has been lauded as genius on several fronts: for his unorthodox methods of choreographing using chance methods; for his revolutionary collaborations in which the dance, sound scores, and décor were created independently of one another; for his pioneering work in using computer programs to generate dances and in creating dances for the camera. He’s been called a boundary-breaker, a maker of road maps for future choreographers, and an artist who challenges audiences with the open-endedness of his work.

And, yeah, that’s all there.

But it’s Merce the dancer — his total awareness and “energy geared to an intensity high enough to melt steel” (as Cunningham himself put it speaking of other dancers) — that I will always remember.

By the time the company became internationally renowned in the 1960s and ’70s, Cunningham was past his technical prime as a dancer. But he never lost the intensity, the clarity, the curiosity that made him a riveting performer well into his eighties. During the recent performances of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at Walker Art Center, the last on stage here before the company disbands at the end of the year, I was reminded of his range as a dancer and his charisma on stage. In RainForest, I watched a splendid Daniel Madoff dance the role that Cunningham had created for himself in 1968, when he would have been around 50 years old. The work summons up a kind of primeval setting where six dancers move like some sublime breed of athlete, ferociously devouring space while pitching their torsos way, way off center, or standing still with the coiled alertness of animals ready to spring. And all of this amidst silver Mylar pillows, designed by Andy Warhol, that drift all over the stage (and sometimes into the audience). The dancers randomly bump into these floating clouds, which suggest a forest at once atavistic and futuristic. As Madoff writhes, struts, lopes through the space, I feel Cunningham’s imprint, his feral intensity.

I’m reminded of a description the late writer David Foster Wallace gives of the tennis player Roger Federer’s aesthetic dimension as a mover: “The human beauty we’re talking about here is beauty of a particular type; it might be called kinetic beauty. Its power and appeal are universal. It has nothing to do with sex or cultural norms. What it seems to have to do with, really, is human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body” (from “Federer as Religious Experience,” The New York Times Sports Magazine, August 20, 2006).

Then I watched the equally splendid Rashaun Mitchell channel another aspect of Cunningham’s dance persona in Antic Meet, a droll, vaudevillian piece that references Cunningham’s love of tap dancing (he declared Fred Astaire among the greatest dancers of the 20th century), his take on Martha Graham with whom he once danced, and his admiration for Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp (albeit the witty costumes and props are by Robert Rauschenberg). My favorite moment occurs when Mitchell struggles with a neckless, four-sleeved sweater as four women wearing Rauschenberg’s costumes – which are a sort of cross between a tent and a parachute — stride around him with dramatically intense Graham-esque gestures. Among them, he seems like a slightly claustrophobic court jester, all knotted up and stalked by harpies. Or maybe he’s a man apart, gleefully and ruefully finding his own way through a tangle of possibilities.

______________________________________________________

Noted and related event details:

Merce Cunningham Dance Company performed the Farewell Legacy Tour show in the Walker Art Center’s McGuire Theater on November 4 & 5.

The exhibition, Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham /Robert Rauschenberg is on view in the Walker galleries through April 8, 2012. All are part of the center’s extensive The Next Stage: Merce Cunningham at the Walker Art Center programming.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Linda Shapiro writes about dance and performance. She was the co-founder and co-artistic director of New Dance Ensemble, a repertory company, from 1981-94.