A Handyman for All Seasons

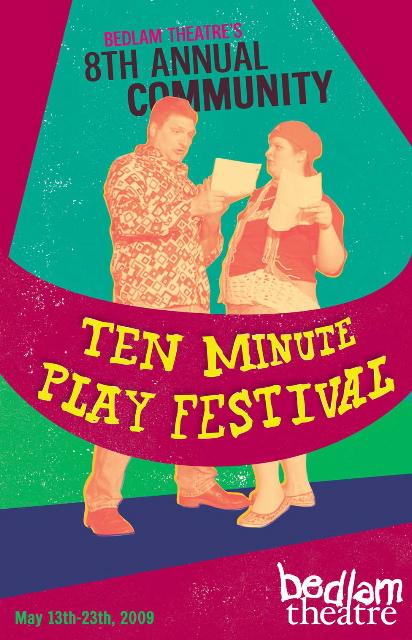

Writer Maggie Sandford profiles Hardy Coleman, a well-received writer and playwright (with a new play in the Bedlam's 10-Minute Play Fest)--and he's a storied, unlikely character in his own right.

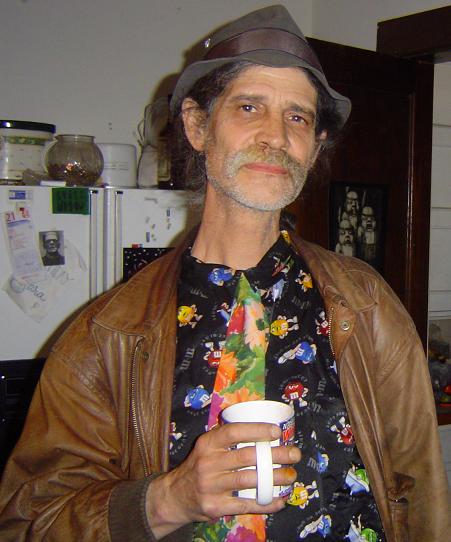

HARDY COLEMAN DOESN’T LIKE TO SAY THAT HE’S A WRITER. “It’s one of the things I do,” he says, smiling into the early spring sun in the courtyard of Minneapolis’ Seward Café. “I don’t wanna be seen as some special guy on a pedestal.” Indeed, in his stained punk rock T-shirt, beat-up leather jacket, and well-worn Fedora, Hardy looks about as down-to-earth as a person can get. “Part of the reason,” he explains, “is like, maybe you need a handyman, you know? Who needs a writer?” The other things Hardy does: carpentry, wiring, plumbing, car mechanics, bike repair; he’s also been a mover, mail-order hub, telemarketer, nursing-home attendant, newspaper delivery man, prison inmate, father, and grandfather. He even worked at the Seward Café before he took off to travel the country by boxcar last summer. “Yeah…I’m an anomaly,” he says matter-of-factly, “Is that the word?”

It is. Though Hardy insists he’s not much of a playwright (he prefers poetry, fiction, and the occasional essay), he’s about to see not his first, but his second play fully produced onstage. Full Count, a gender-wary look into the life of a young mother, is one of a dozen other one-acts in Bedlam Theatre’s ongoing Ten Minute Play Festival.

Hardy’s piece explores such disparate subject matter as etiquette, femininity, and baseball — not all of which is run-of-the-mill material coming from a working man of 56. Hardy explains himself this way: “Most of my writing I do for somebody. It’s rare that I’ll write something for myself.” And in this particular piece, Hardy pays homage to his good friend, Rah Kojis, a young single mother, actress, puppeteer, fire-dancer and regular on the Bedlam stage. “She’s just an incredible person,” Hardy says tenderly, “The way she is with her kids…and she can do amazing things with fire! But she’s a shortstop not a catcher. [The female lead] had to be a catcher, for the play, y’see? On the field, the catcher’s role’s at the heart of it all.”

What distinguishes Hardy’s anomalous sensibility is that he writes about working-man stuff, but he thinks like an artist. He finds godliness in baseball, miracles in biking, ballet in the moving of furniture from van to house. Hardy grew up, for the most part, in small-town Texas. He claims he started “really writing” in high school, but he’s always been a storyteller; as a youth, he used to weave “wild, made-up stories” for his six brothers and sisters, just as he’d heard similar tall tales from his father, a doctor. “He used to take big old medical text books and play like he was reading from them,” Hardy remembers. “Crazy stories.”

It’s clear from Hardy’s voice that his father’s influence runs deep. In fact, even the day of his father’s death was inextricably entwined with Hardy’s work as an artist. On the advice of a friend, Hardy enrolled in a play-writing workshop where he reworked a piece he’d been sitting on: Perfect In Memory, the true story of Hardy, his drug dealer, and a phone call with his mother, who was dying from Alzheimer’s. The workshop’s leader wanted to see Perfect in Memory onstage; so Hardy, despite the fact that he’d not acted since high school (and even then only badly, he says), wound up playing himself. It was under these already emotional circumstances that Hardy’s father died, just hours before the final performance. “The tears were real, that night,” he says, nodding. “That was the last time I cut my hair off. I’ve only cut it twice since getting divorced the second time: once when my mother died, once when my father died.”

________________________________________________________

“It’s better to do it than to read about it. You’ve got to get your hands dirty, own it.”

________________________________________________________

According to Hardy, writing has helped him weather some of the darkest times of his life, but “it hasn’t always been there,” he says. “It wasn’t there before I went to jail.” In 1992, Hardy was sentenced to 16 months in the Duluth Federal Prison after being found guilty of counterfeiting postage stamps. He describes the time leading up to his conviction as rock bottom: he was struggling to keep his second marriage from falling apart and his mail-order business afloat, and he slipped into temptation. “I was lying, drinking, stealing. You start to see it as a game, when you engage in criminal activities like that.” But remarkably, prison ended all that. “I started writing the day I went in — picked up a pen and paper and just wrote about everything I could, mostly about life on the outside and how you miss it, and stuff for the other guys inside.”

When he got out, Hardy’s friend had a job waiting for him, even if his wife wasn’t. He went about rebuilding a life, one that included writing. Over the years, Hardy’s work has been published in national magazines — though he doesn’t remember or care which ones — and he has even been paid for his writing from time to time. He describes his biggest pay-out to date: a new-age composer (who Hardy respectfully leaves nameless) heard him perform at a poetry slam under the name Crazy Rabbit, and asked if could he use some of Hardy’s material in his music; The composer offered him a choice: $500 up front or he could wait for futures. Hardy, whose truck had a broken carburetor at the time, took the money. He explains politely that he didn’t much care for the composer’s work, or the whole idea of an art scene; he’s more interested in people like him, who work for a living. “It’s better to do it than read about it. You’ve got to get your hands dirty, own it.”

Today, Hardy finds work where he can and lives in a house with a handful of young transients, bike-builders and punks – an unlikely crowd, perhaps, for a self-described “old guy.” But he likes the freedom in this lifestyle — dancing, making music, drinking, moshing. “The only difference is the injuries don’t heal as fast as they used to,” he says with a smile. Still, Hardy bikes everywhere and, after 36 years in Minnesota, he says he’d rather work outdoors, even in the cold, than be stuck inside. And every summer he takes time out to hop a train or a bus and visit his three adult children. Hardy’s practical advice for train-hopping might just as easily be applied to writing: “Pack what you need, and not what you don’t.”

*****

Related events: You can see Hardy Coleman’s short play, Full Count, in Bedlam Theater’s 10-Minute Play Fest, May 13 through 23.

*****

Hardy Coleman (“no relation to Norm”) can be reached at hardycoleman@riseup.net.

About the author: Maggie Sandford is a Twin Cities-based writer and performer with roots in Seattle and New York. She writes essays, travel journalism, fiction, humor, poetry, and film, with a particular interest in the relationship between art and science. Her work has been featured at ComedyCentral.com, NYTimes.com, OnlineAdventure.com, and on National Public Radio.