Exhibitionists

Artist and sometime local historian Andy Sturdevant investigates the shadow gallery circuit of in-home exhibition spaces, and talks with these DIY gallerists about the hows and whys of opening their homes to the public to show artwork.

So this was London at last, and nothing gave me more pleasure than strolling around my new possession all day. London seemed like a house with five-thousand rooms, all different; the trick was to work out how they connected, and how to walk through all of them.

-Hanif Kureishi, The Buddha of Suburbia

BEFORE WE GET TO THE MAIN ATTRACTION, LET’S PEER BEHIND A FEW CLOSED DOORS for a moment. It’s only befitting for a piece like this that I invite you, the reader, into the back room, where you can watch me rearrange the dessert tray and make awkward small talk about my opening-night party preparations before the guests arrive.

I have wanted to write a piece about semi-permanent exhibition spaces in people’s living quarters since I set foot in a cramped apartment show in Uptown for the first time nearly a year ago (more on which later). Now that we’re staring down the proverbial financial Armageddon, the time and setting seem perfect to talk about such alternative models for showing work. And what better language to couch such a conversation in than the lexicon of panic, leanness, and unwilling indigence?

So in my early conceptions for this piece, my initial plan was to come at you Old Testament-style in this opening paragraph. You were going to get the litany of closings, hiatuses, collapses and calamities that plagued the art world this year, both locally and nationally, followed by some light hand-wringing and concluding with an appeal for all of us to find a better way. The old “sorry folks, fun’s over, the economy’s collapsing around you and art as we know it is utterly doomed” angle.

Except that approach is all wrong. I knew I’d need to abandon it after coming across a piece by Holland Cotter in The New York Times a few weeks ago, enthusiastically entitled “The Boom Is Over. Long Live the Art!” Online, the piece was accompanied by the image of the late David Wojnarowicz in an Arthur Rimbaud mask, sitting in a diner drinking coffee, from his Mayor Koch-era photographic series Rimbaud in New York.

The image and the piece resonated with me, as Wojnarowicz and his peers were some of the first contemporary artists I admired in my youth. As a teenager coming out of my adolescent pop fixations, he and the New York art scene of the 1970s (Basquiat, Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith) seemed like impossibly heroic figures, simply by virtue of their accessibility and ramshackle, D.I.Y. approach to art making. As it happens, New York City was in a drop-dead economic freefall during that time that was at least as bad as our present situation.

In his introduction, Cotter offered a feature-length meditation on the parallels between that era and ours. He gives an overview of how much of the current infrastructure for supporting, showing, and funding art is collapsing; but it’s also an utterly joyous piece, a paean to those downturn values of flexibility, adaptation, and imagination. Reading it reminded me how much more interesting life can be – has to be – when your options are severely limited by access to money. The author writes of Wojnarowicz’s troubled times like this:

With virtually no commercial infrastructure for experimental art in place, artists had to create their own marginal, bootstrap model. They moved, often illegally, into the derelict industrial area now called SoHo, and made art from what they found there. Trisha Brown choreographed dances for factory rooftops; Gordon Matta-Clark turned architecture into sculpture by slicing out pieces of walls. Everyone treated the city as a found object.

Of course: the city as found object. I read Kureishi’s Buddha of Suburbia, quoted above, about the same time as I was discovering the Lower Manhattan of the 1970s. I remember being enchanted by the idea of a city as an extended suite of spaces you were free to move through, navigating by way of tenuous interpersonal connections and charm. Public spaces, private spaces; they were all accessible if you knew the territory and were willing to put in the footwork. Money and infrastructure didn’t matter.

These were the thoughts I had – freedom from infrastructure, the urban fabric, public/private spaces, the joy of improvisation – as I attended an exhibition at an ad-hoc “gallery” dubbed Seltzer about a year ago, long before the worst of the economic collapse.

________________________________________________________

I remember being enchanted by the idea of a city as an extended suite of spaces you were free to move through, navigating by way of tenuous interpersonal connections and charm.

________________________________________________________

Seltzer is an exhibition space only in the very loosest sense. The vast majority of the time it’s just the Uptown apartment of two MCAD graduates, Isa Gagarin and Michael Mott. Occasionally, though, they clear out their living room, bedroom, and bathroom, and ask an artist in to put up some work; they invite some friends. At that point, the space miraculously transmogrifies into Seltzer. The show I saw consisted of work by the Hardland/Heartland collective, but they’ve also shown work by Tynan Kerr, another recent MCAD graduate, and the Chicago-based artist, Loren Erdrich, at various points.

Of course, I’d heard of such spaces before, but Seltzer was the first I’d ever experienced firsthand while living here in Minneapolis. (I can’t even recall how I found out about the show; a long-lost mass email or online announcement, perhaps). Once I had seen Seltzer, though, I seemed to hear of more and more similar, loosely-allied spaces, located in basements and apartments and lofts and houses and even hallways-one-off affairs or permanent spaces, connected by lingering undergraduate ties, professional relationships or friendships, promoted with homemade fliers handed off to acquaintances at coffee shops or college classes or gallery openings.

These shadow galleries are much like Kureishi’s London, a system of interconnected rooms one learns to navigate through informal channels, which operates, paradoxically, as both a supplement and a critical response to the traditional art exhibition circuit, with no regard for commercial viability or critical visibility. Of course, any abandoned warehouse or storefront can and should be pressed into service as an impromptu gallery space, but using your own home for the purpose is a more intimate, more utilitarian use of resources (and certainly less of a logistical hassle than navigating the legal and financial issues related to occupying such a space). And, as more than one home gallerist told me, “You’re paying rent anyway.” It creates the type of space, in other words, that is perfectly suited for lean economic times.

There’s always precedent for such things, and one of the greatest here in Minneapolis is the Walker Art Center. The museum has its origins in the drawing room of lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker in the 1879, a space in his Kenwood mansion where he exhibited his art collection salon-style for guests and, later, for the public. Walker was not lacking for funding, of course, but in the city at the time there was no infrastructure for showing what we now refer to as “new work.” So Walker created his own space, and it eventually grew into the sturdy, metallic edifice on Oak Grove Road and Hennepin Avenue we know now. The fundamental impulse to create space with what one has immediately available – one’s own home – is similar today.

Back to Seltzer: I asked Michael and Isa how they had come to create the space, and they told me it actually “began as a sort of joke, a way of giving our friends a ‘Solo Exhibition’ on their résumé.”

This does sound like a sort of joke until one thinks about it further, with more careful consideration to Gagarin and Mott’s belief that “the chance to show some work in a space shouldn’t be a crazy once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Indeed, it should not; so, when the need arises, a space is improvised to serve that purpose. Seltzer’s programming is highly irregular, but they may have some events coming up. I don’t even know myself. You’ll have to be flexible.

The Seltzer artists referred me to a number of other artist/curators whose work included setting up, at some point or another, spaces in their living areas. I’ve been fortunate enough to talk to a number of these people; the various origin stories for these far-flung spaces are fascinating.

Filmmaker, photographer, and artist Matt Bakkom hosted a space, very near the Walker, for some time which he referred to as “Under.” Under comprised the three rooms of a basement apartment he was renting on Hennepin Avenue near Franklin, and it served as the site for a few one-person shows through 2005-06. Like the Seltzer artists, Bakkom’s interest was in showing one artist at a time; he created Under, in part, as a reaction against the near-impossibility of landing such an arrangement in one of the city’s galleries. Artists were drawn to showing there work there to have something prominent-sounding on the CV, of course; but they were also attracted because the arrangement itself facilitated a sort of freewheeling creation, the kind of thing possible only when a single artist is given free reign in an open space.

In a sentiment many others echoed, Bakkom explained that when a show can be “presented free to people in casual way, it takes the intimidation factor away.” Gallery spaces can be off-putting to non-artists, so presenting work in a living space, stripped of the formal, chilly distance of an institutional setting, can be refreshing. The resulting shows have a rent party aesthetic – Bakkom was quick to point out that people only come to openings anyway, so even if you charge them a few dollars for a cup at the door, it’s okay; visitors come by for the event as much as for the art, which is often on view just for one or two nights. The host has recouped his (probably nominal) expenses; the artist has gotten a chance to stretch out and work alone in a contained, idiosyncratic space; and the gallery-going public gets to feel like they’re on the inside of something, and have a good time doing so. It creates a sense of community, in the way that can only be created by inviting people in to your house. The intimacy of such an invitation, in this context, puts regular gallery-goers in the position of being guests, even trusted friends.

Unfortunately, I never saw a show at Under, and after exhibiting work from such artists as Mark Wojahn and Abinadi Meza, Bakkom has since moved elsewhere. But the concrete encasements and built-in woodwork he describes – describing them, of course, in the sort of way one fondly describes the features of a place they’d made their home – leave me sure I missed something fascinating. I have, however, been fortunate enough to see a show at the space called Plateau, run by two other MCAD alum, Mitchell Dose and Dan Tesene.

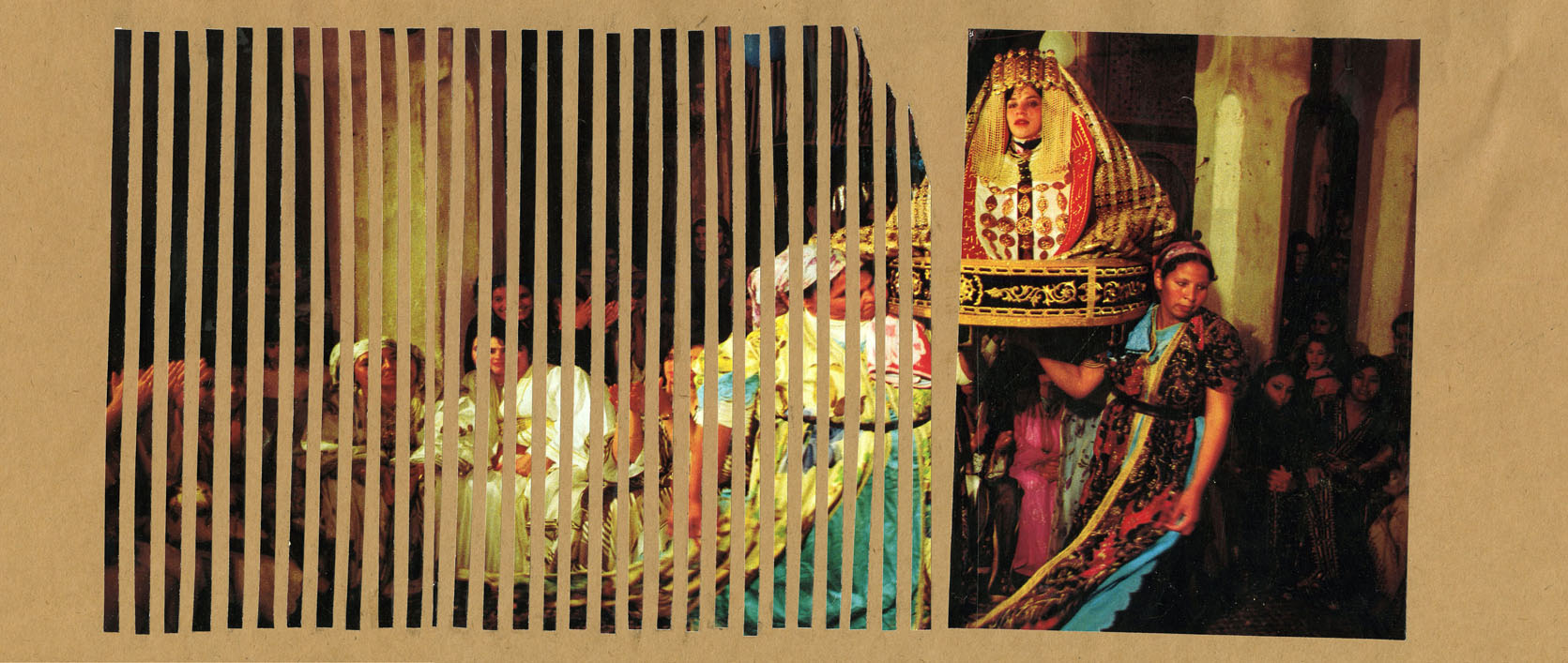

Plateau is located over the Open Eye Theatre in the Phillips/Midtown neighborhood of Minneapolis, in a loft-style, third-story apartment. At a show in the Plateau space, unlike an exhibition experience at Seltzer, you scarcely know you’re in someone’s apartment. For the opening I attended (La Raccolta, this past December), all furniture had been spirited away, and there was track lighting installed in the ceiling for the occasion.

Still, knowing you are in someone’s apartment invariably colors your experience in interesting ways. On the other hand, Dose, an installation artist who works with fabric and paper, made the counterpoint observation that showing artwork in one’s living space creates a situation that removes the foreknowledge and preconceptions one might already have of an established gallery space – the viewer’s perception of the work is not mediated by the history or reputation of the space, which allows for a more open-ended, neutral experience.

Plateau is an ongoing experiment, so be vigilant for word of future openings. They have also produced a number of books and catalogs, most recently for the La Raccolta show.

From Mitchell Dose, I got word of a few other home gallerists, one of whom is Kari Pearson. Pearson’s shows, which took place in the hallway of an old apartment building (dubbed the Garfield Gallery, in deference to the street on which it’s located), were smaller-scale undertakings than the others described here; in that sense, Pearson’s enterprise was perhaps truest to the sense of possibility and flexibility inherent in these types of exhibitions. The hallway space, with its extraneous doorways and wooden framework, naturally lent itself to creating series of self-contained vignettes. She put the hallway space to use for two shows in 2007: one exhibition showing her own work and that of a small group of friends to celebrate the Day of the Dead; and another show, marking Pearson’s 25th anniversary as a working artist, which featured art Pearson had made from childhood through her undergraduate years. These are just the kinds of idiosyncratic thematic ideas that thrive in a house show setting. Artwork that might seem precious in a commercial gallery makes perfect sense in a one- or two-room residential context, seen in an apartment with thirty other people and some drinks.

________________________________________________________

Showing work in this way is a sustainable practice, one that can be given a lot of time and energy when such resources are available, but which can fade into the background when they are not, or when interest has flagged.

________________________________________________________

The final stop through our shadow gallery circuit is the oldest, continually operating such space I know of, housed in Aaron Van Dyke and Peg Brown’s St. Paul duplex, which has had a part of the first floor set aside specifically for their Occasional Gallery since early 2003 (in 2007, in fact, Patricia Briggs interviewed Van Dyke about Occasional on this very website). Van Dyke, a professor at MCAD, had been familiar with apartment galleries in Chicago – a proliferation driven by more artists, more recent graduates, more schools, presumably – but he found no such arrangements when he moved here.

True to the gallery’s name, the couple has shown somewhere between eight and ten shows since it opened, spaced intermittently depending on the curators’ and artists’ availability, energy and respective scheduling demands. Van Dyke and Brown have, thus far, featured artists from all over-people they’ve met, whose work interests them. Here we find one of the most appealing aspects of running such a space, especially as compared to operating a similar nonprofit or commercial exhibition venue. Showing work in this way is a sustainable practice, one that can be given a lot of time and energy when such resources are available, but which can fade into the background when they are not, or when interest has flagged. Occasional Gallery’s method has been to show work by one or two artists for six to eight weeks, with one opening in the late afternoon and early evening, followed by regular gallery hours on the weekend and opportunities to come in by appointment. They send exhibition announcements through a regular mailing list but, like most of these spaces, the couple relies largely on word-of-mouth to reach their audience.

But there’s a delicate balance to maintain when spreading the news; all house gallery proprietors engage in something Kari Pearson called “under-inviting.” There are inevitable logistical considerations that arise when inviting a hundred people into your house, so you have to create promotional methods that allow the audience to self-select, to naturally limit itself. There’s no overhead to meet, after all-no target figures for grant proposals one needs to reach. A hundred guests, perhaps 150 – typical for an Occasional opening, Van Dyke told me – is ideal, an ample number but manageable enough for all involved to be comfortable.

There is another aspect to all this that Van Dyke mentioned, something that relates more to the experience of the curator-gallerist than it does to that of the audience or to the artist. Living with art, as anyone knows, is a much different than experiencing it in your professional space, even if that artwork is hanging in your own professional space. This is part of the attraction that undoubtedly fueled T.B. Walker’s early salon, and which continues to fuel at least a part of these gallerists’ interest in maintaining exhibition spaces in their homes. In so doing, they can be close to the work, get to know it intimately.

Van Dyke writes essays and publishes catalogs for each Occasional show, much like Plateau does; in living with the work, Van Dyke says that he finds he can more easily and freely talk about it with authority. At an opening, just passing by, “no one looks at art enough,” he acknowledges. Putting the artwork in your living space affords the kind of intimacy and knowledge that only comes from living side-by-side with the work, from seeing it daily.

At its best, a city, like Kureishi’s London, does seem like five-thousand rooms, all connected somehow, all somehow implicitly commenting on, complementing, or critiquing each other. Taking art out of institutions and putting it onto “the streets” has long been suggested as a solution to stagnation and a host of other existential art-world afflictions. Why not conceive of “the streets” literally, as five-thousand interconnected rooms, in apartments and duplexes and bungalows, cleared of furniture and supporting the work of artists at all points in their careers?

One more piece I took away from all these conversations, something which came up repeatedly as we talked over the phone, in person, over coffee, or in these spaces. Nearly everyone I spoke with encouraged me, personally, if I had any inclination whatsoever, to clear out my basement or living room and invite a few artists I know to take a crack at filling it for an evening. If we are, in fact, entering a long era of hope-tinged communal austerity like Cotter or, hell, even Obama suggests-this does seem like a perfectly appropriate response to the circumstances. And really, what do you have to lose? As these DIY gallerists told me again and again, you’re already paying rent on the place, anyway.

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a Minneapolis-based artist, curator, and writer who is a regular contributor to ARP! and Secrets of the City. He curated the History Room: 20 Years of No Name and the Soap Factory exhibition at The Soap Factory last season, and he is currently working on an accompanying book about the gallery’s history. Andy is also a contributor to the Electric Arc Radio Show music and performance series at the Ritz Theater in Minneapolis.