*Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published in July 2008. Interested readers should note that the annual Community Collaboration Hot Metal Pour at Franconia Sculpture is coming up August 1, 2009; in addition, the park’s Annual Arts and Artists Celebration & Festival will be September 26. Visit the website for Franconia’s summer-long schedule of events.

IT’S NOT TYPICAL METRO AREA MYOPIA TO SUGGEST that, naming-wise, there is a strange otherworldly quality to the parts of our state lying outside the 694 loop. Take a look at a good, detailed map of Minnesota sometime and think about those place names you see: The Boundary Waters, The Arrowhead, The Iron Range, The Northwest Angle, The Driftless Area, Pipestone, Blue Earth, Yellow Medicine, The North Shore. Do these seem like places you could actually drive to in your Honda Civic and buy a hot dog? No, these places sound more like regions of Middle Earth, more like the fever dreams of a teenaged Dungeons & Dragons player than they do the major geographic areas and outlying counties of a typical U.S. state. Ours is a wild, wide-open region that, outside of its urban and suburban areas, is almost entirely defined by its natural characteristics. It seems sometimes as if the whole world is being overtaken by pavement and fluorescent lighting; but if you start in downtown Minneapolis and drive a hundred miles in any direction, you can easily find yourself someplace that seems as far away from that world as Narnia or the Fire Swamp.

_________________________________________________

“Franconia” is one of those Middle-Earthly Minnesota place names that conjures up visions of otherworldliness, with a colorful history that calls to mind words like “palatinate” and “bishopric.”

_________________________________________________

“Franconia” is one of those Middle-Earthly Minnesota place names that conjures up visions of fantastical otherworldliness. Historically, the original

Franconia was a region of Bavaria with a colorful history full of Holy Roman Emperors and words like “palatinate” and “bishopric.” One wonders how the township of Franconia, Minnesota got this name, as it bears little resemblance to the dense, heavily wooded hills of southern Germany – perhaps the predominantly Swedish immigrants that settled the area had a keen sense of irony. Minnesota’s Franconia, about fifty miles northeast of the Twin Cities, is situated on a long, flat stretch of prairie that runs alongside the St. Croix River, from the hillier parts of the southeast all the way up to the Iron Range. It’s one of those areas which—but for a few barns, trees and water towers poking up every so often—is so flat that you see nothing, for miles, except the horizon. It is a wind-swept area. You get out of your car, and that’s what you’ll hear: wind sweeping. In the middle of this terrain, where Highways 8 and 95 meet up, you’ll find the

Franconia Sculpture Park.

It’s precisely this sort of what we’ll call, um, Minnesotan otherworldly nothingness—a twinned sense of evocative, obscure nomenclature and panoramic flatness— which makes Franconia such an excellent place to work as a sculptor. Standing in the middle of the park on a recent June afternoon, I looked all around me and found it hard to make out where, exactly, the park ended. The neatly-mowed areas that surround much of the work onsite gradually give way to waves of tall grass that seem to stretch past their boundaries, way off into the distance.

_________________________________________________

It’s precisely the twinned sense of evocative, obscure nomenclature and panoramic flatness, which makes Franconia such an excellent place to work as a sculptor.

_________________________________________________

For all you can tell by looking around you, Franconia might stretch on in neat little patches of art and grass for hundreds of miles. Something about the sweeping vistas must activate a latent crypto-Scandinavian work ethic that lies deep in a Minnesotan’s genetic make-up. “Well,” one thinks, “here I am, out on the prairie. There is nowhere else to go. Time to get some work done.” And it’s not easy work, either, but the sort of back-busting, roll-up-the-sleeves frontier work you read about in

Laura Ingalls Wilder novels.

And Franconia is, indeed, a place where work gets done. The park itself is nineteen acres, with space parceled out for the twenty-five or so artists who work there, primarily during the spring and summer months. Spread across the acreage is an appealing visual jumble of large-scale art and the tools of large-scale art-making – cranes, forklifts, rusty sheds, scrap metal. At the entrance of the park is a large, white, communal house, where the Franconia resident artists live, sleep, eat and share chore duties. It’s the great American frontier myth come to life: people workin’ hard, helpin’ their neighbors and sharin’ the land! *When naysayers and traditionalists want to slap down contemporary art, they’re prone to complain that it’s fundamentally insubstantial—that it’s all navel-gazingly cerebral and mindlessly transgressive, comprised of nothing but critical theory, clever tricks, and self-consciously-worded manifestos. A trip to Franconia disproves that ridiculous assertion entirely. The artists out here can match any culture warrior (old or new) you’d care to name, blow-for-blow, in the field of practical creative know-how like, say, welding torch operation.

_________________________________________________

It’s the great American frontier myth come to life:

people workin’ hard, helpin’ their neighbors and sharin’ the land!

_________________________________________________

When I visited, my guide for the day was Jamie Barber, a recent graduate of the University of Minnesota sculpture program who is serving an artist-intern at Franconia for the season (and is, incidentally, an accomplished welder, too). The artist-interns live and work at the park in two-month shifts, with three shifts covering the warmer months. They are allotted a space to work and full access to the park’s facilities, as well as a bed and three meals a day, in exchange for doing the sort of work that keeps a park like Franconia open and operating. It is a park, after all, fully-operational and in need of staffing, maintenance work, mowing, grounds-keeping and all the rest of it. The interns work seven days a week, beginning at 8:30 and working until noon; then, they have the rest of the day off to make art and interact with visitors and fellow park residents until the dinner bell rings (yes, there is an actual dinner bell). As chores are split, so are cooking duties; the artists switch off handling daily meal preparation in the communal farmhouse, where they eat together and sleep in shared quarters. Everyone pitches in.

Here, one is reminded of the natural rhythms of farm life – up with the sun so there’s maximum light to work with, and by the time the sun is at its highest and hottest in the afternoon, most of the really difficult outdoor labor has been completed. It is jarring for me to think of an internship in this way. Internships in the art world typically call to mind such backbreaking feats as getting the red wine from the bottle into the plastic cup without spilling any of it on a donor’s name tag. The rewards of such a bucolic internship are obvious, too. Jamie had to forgo a trip out to the fishin’ hole with his colleagues to finish giving me a tour of the park on the hazy Sunday afternoon I was out there.

_________________________________________________

It’s jarring to think of internships this way. In the art world, internships typically involve such backbreaking feats as getting the red wine from the bottle into the plastic cup without spilling any of it on a donor’s name tag.

_________________________________________________

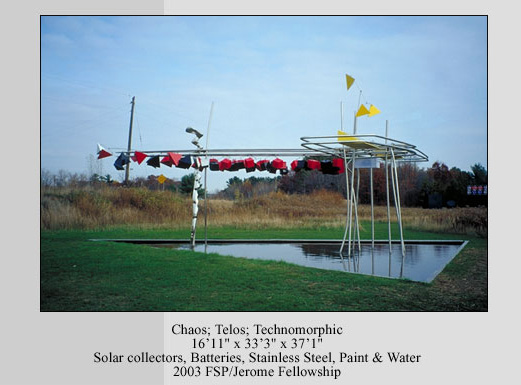

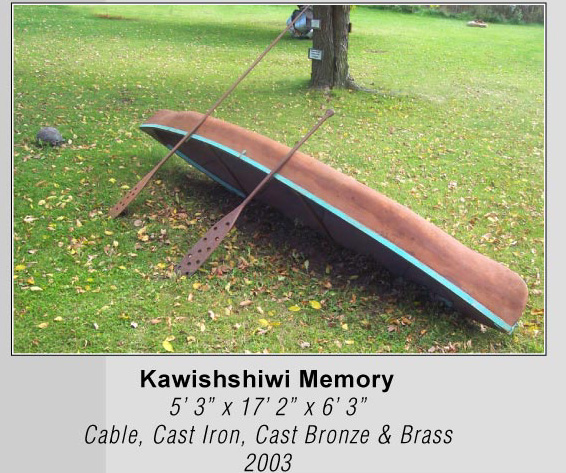

Also out there at Franconia are the

Jerome fellows, sculptors who have been granted a two-year residency to live and work in the park, and who do so alongside the interns. Another outstanding aspect of the park is the fact that all of the artwork you see is more or less created, stored and displayed in the same space. You can examine the complete spectrum of sculptural practices in play today – from stately minimalism to over-the-top whimsy; but you can also get a good sense of the full of range of the sculptor’s career, with representative pieces from artists just out of undergrad to internationally-known veterans of the scene with work in major museums and collections. It’s a space where all of these people, at all points in their careers, live and work together in full of view of anyone who cares to stop by, get out of their cars, and take a look around.

Working out on the prairie, of course, is much different than working in the hermetic environment of a private studio. The communal quality of the park and interactions with visitors it provides make for a much more open-ended sort of working experience; but, obviously, those prairie-specific otherworldly qualities of the landscape itself come into play as well. The best work is that which can’t help but react to (or, better yet, interact with) Franconia’s peculiar outdoor environment and the passage of time in which resides there.

Most of the work is on display at the park for two years. This recent visit was the first I’d made out there in perhaps a year-and-a-half, so some of the work was familiar to me from my last trip. It was fascinating to see how the sculptures had changed in the intervening time.

_________________________________________________

After a few seasons sitting through Minnesota’s brutal freeze-thaw cycle, Metalmatic looks like it could be a thousand years old – with all the gravitas of a natural formation which has endured over epochs, rather than the crumbling decay

suffered by structures made by human hands.

_________________________________________________

I admired

Kari Reardon’s Metalmatic when I first saw it, but after sitting through Minnesota’s brutal

freeze-thaw cycle for a few seasons, the voluminous steel sculpture has acquired a remarkable rust patina which lent it an undeniable authority I hadn’t been aware of previously. The size was impressive from the start, the way the sculpture’s curves follow a lazy cycling motion skywards, but the textural changes wrought by time make the scale of the piece all the more credible. Now, it looks like it could be a thousand years old – with all the gravitas of a natural formation which has endured over epochs, rather than the crumbling decay suffered by structures made by human hands. A similarly serendipitous interaction with the environment is at work in

Donald Myhre’s Dave, Don and Jeff. His is another piece I recalled from an early trip to the park; but I remembered it more as an ambitious bit of sinister, large-scale whimsy: three brothers, nine feet tall and swaddled in metallic silver space-invader hooded robes, gazing out over the park with chalky white, impassive faces. However, in the time since I had last seen them, the silver on the brothers’ robes has begun to flake off substantially, revealing the neutrally-toned cloth underneath in crackling irregular patterns. There is still a sense of whimsy, but it is much darker. I have no idea how intentional this transformation might have been; but regardless of Myhre’s intent, the effect succeeds in giving the trio of figures a sense of weariness and travel fatigue that complements the alien flatness of outstate Minnesota around them. One has the sense that these three are visitors in a strange, unexplored world. The weathering serves additionally to underline the piece’s unspoken central idea—one that I recognize, having two brothers myself. The sculpture’s wear suggests that the fraternal bond can, itself, make for a perilous and exhausting journey.

A piece being created during my recent visit by McKeever Donovan, another artist-intern completing his BFA in Chicago and cycling through the end of his tenure at Franconia, draws more explicitly on the advantages of working and exhibiting outdoors. The piece is a room-sized structure with no roof, created from discarded wooden packing crates recovered from the park’s impressive back stock of miscellaneous supplies. Donovan was filling the structure with overstuffed thrift store furniture and seeding it with fast-growing vines. All of this is sealed off to the viewer, visible only through a peephole. Over the two years the sculpture will sit in the park, the vines will feed off the rain and sunlight, growing over the furniture until the vegetation eventually overtakes the whole thing in a sort of eco-apocalyptic tableau. The day before I arrived, the structure was carried by crane from the workspace, over a few hundred yards, to the space where it will be exhibited. Anyone stopping by the park that day would have had the pleasure of learning how functional materials (crates, for example) can be recycled into art objects; and, then, they would’ve been treated to the spectacle of a gaggle of artists operating a multi-ton crane to transport said art object.

_________________________________________________

Franconia is a community of artists that is out there on the prairie, outside the city’s larger art community; but it’s also wide open, literally and completely, for anyone to engage it as much or as little as they care to. If that includes learning firsthand about the role of cranes in the conveyance of contemporary sculpture, all the better!

_________________________________________________

That’s the contradictory nature of the place – Franconia’s out there on the prairie, outside the city and the larger Minnesota art community; but it’s also wide open, accessible to anyone who would like to stop in, be they day-trippers up from the metro, or curious locals, or students, or those who happen upon the park just passing through. And, that is to say, it’s a community of artists that is wide open, literally and completely, for anyone to engage it as much or as little as they care to. If that includes learning firsthand about the role of cranes in the conveyance of contemporary sculpture, all the better! Come one, come all!

Case in point: the Sunday afternoon in June I was at the park, Holly Streekstra was putting the finishing touches on her wonderful Porta Obscura, a lavishly-appointed, old-timey walk-in camera obscura. It’s actually built on to a trailer, very much in the style of the sort of roadside attraction you see driving across the Midwest. Her parents had been in the park the night before to help her celebrate; Jamie informed me that Franconia tradition dictates that visiting parents, on the eve of their child’s opening, bring potluck food with them for the big event. So, when I was there, everyone was walking around with platefuls of Streekstra’s mother’s potato salad and slices of her outstanding apple pie, offering them to visitors and to me (the pie was delicious). Holly Streekstra is an artist who has shown all across the country and whose work is viewable in a number of notable galleries and collections. Of all of these esteemed venues, however, it is only at Franconia that you can see her installing her work and perhaps even talk to her about it; and, if you show up at the right time, you could also have a piece of her mother’s homemade apple pie with her and with the park’s other artists and visitors.

_________________________________________________

If you’re familiar with typical, institutional exhibition spaces–where you rarely see the artists themselves, much less the process by which they create or install their work–you can appreciate how radical Franconia’s ethos of complete public access really is.

_________________________________________________

If you’ve ever been in a museum, you know that you rarely see the artists in the process of creating or installing their work (really, you seldom even see the artists

at all). And if you’re familiar with these typically institutional exhibition spaces, you can perhaps appreciate how radical the kind of access Franconia Sculpture Park affords really is. When I spoke to director

John Hock, who is a sculptor himself, he explained that this radical openness allows exactly the sort of access he had in mind when he founded the park twelve years ago. Franconia’s is the sort of environment that encourages real dialogue, real interaction with the viewing public. When you see something in a museum setting, it’s as if the artist’s work was simply transported, fully formed, from studio to museum, just like that, as if by magic; there’s seldom any transparency or participation in the process of art making or installation on the part of the viewer. Is it any wonder people sometimes feel so alienated from contemporary art? People standing in a museum often look like Myhre’s Dave, Don and Jeff, lost in a remote and alien world.

In this heated political season—with all of its attendant

howling about “elitism” and the role art should or should not play in our public lives—Franconia presents an exceptionally inspiring model for how art and the general public can interact to everyone’s benefit. It works because the artists are out there learning from each other and from the visiting public, and vice versa. Franconia is a solid refutation of the sort of

culture war tactics employed by the late Senator from North Carolina – it’s “a uniter, not a divider,” in the argot of our time. Facile words like “values” get glibly tossed around, especially in hotly contested election cycles like this one, and

especially in reference to Helmsian demagogues. But I think you can really use a word like “values” to describe Franconia Sculpture Park – it is a place that values openness, hard work, camaraderie, education, and ingenuity. And the pie is delicious. Dig in.

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a Minneapolis-based artist, curator and writer who is a regular contributor to

ARP! and

The Rake’s Thousandth Word blog. He curated the

History Room: 20 Years of No Name and the Soap Factory exhibition at

The Soap Factory this year, and is currently working on an accompanying book about the gallery’s history. Andy is also a contributor to the

Electric Arc Radio Show music and performance series, which is beginning a new season at the

Ritz Theater in Minneapolis this fall.