Peng Wu: Many Ways of Making Home

A conversation with the 2022/23 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on creating participatory spaces for collective struggle and shifting from studio practice to dinner table practice

In this interview, interdisciplinary artist Peng Wu weaves together deeply personal queer experiences with the history of alien labor in North American colonialism, in order to challenge oppressive narratives and foster healing, liberation, and resilience.

Melanie PankauYou describe yourself as an interdisciplinary artist and designer that collaborates across disciplines and cultures to create participatory art installations to address various urgent social issues including immigration, health disparity, and queer rights. Could you tell us more about your practice and the contemporary art strategies you use to talk about these topics in your work?

Peng wuAs an interdisciplinary artist and designer, I explore strategies that effectively create spaces fostering alternative modes of knowing—knowing oneself, other human or non-human beings, history, and most importantly, the relationships among them. The way we think is constrained by the physical spaces society has designed: classrooms, galleries, city streets, and parks. These spaces subtly influence our eagerness to engage in dialogue and the subjects we touch upon, thus perpetuating the oppressive nature of the system.

Drawing from personal struggles, including growing up queer in China, immigrating to the U.S., and dealing with chronic sleep disorders, I strive to create public spaces that center on marginalized communities, oppressed histories, and voices, hopefully contributing to a more just future. Exploring strategies such as interdisciplinary collaboration, collective artmaking, community building, installation, and performance, my practice prioritizes the integration of art into everyday life and emphasizes that these approaches extend beyond Western contemporary art. Artmaking serves as a means to understand the personal, social, and historical root causes of our collective struggles and to create spaces for sharing this knowledge, ultimately fostering opportunities for healing, liberation, and resilience for those who share similar experiences.

For instance, the Jin Paper Burning project is a participatory workshop that serves a practical purpose: addressing the longing to communicate with our ancestors in the Chinese, Asian immigrant, and diaspora communities. This project was reinvented based on the family tradition my father taught me when I was young, influenced by the spiritual ritual of burning joss paper still practiced in China and many Asian countries. When my father passed away during the pandemic, I felt the urge to keep the tradition alive. The project rejects the messages preprinted on commercially available joss paper, which often represent capitalist and sexist values. During the workshops, participants deeply reflect on their life concerns and relationships with their ancestors, using linocut printing on handmade paper to create individual messages for their loved ones. In the end, we burn the handmade joss paper together to send the messages to the other realm. I have hosted workshops in galleries in China and the U.S., as well as public libraries, bookstores, and my backyard.

MPYou have produced several participatory events about insomnia and sleeping. How did these projects originate and what manifestations did they take? How were the participants affected? What did you learn from their interactions in the environments that you created?

PWDuring the time I was trying to secure my next visa renewal, I noticed my insomnia getting worse. Night after night, I couldn’t sleep. Without health insurance at that time, because I had just quit my corporate job, I could not seek medical help. So, I turned to my inner artist and said, “Okay, you solve this, please!”

I proposed the idea of searching for a cure for my insomnia as an art project to the curator at the Weisman Art Museum. The University of Minnesota Medical School soon funded the project through the Target Studio for Creative Collaboration residency at the museum. I thought to myself, “Oh, they must be as desperate as me!” After a year of research with a sleep scientist, I understood the sleep issue as a severe global public health crisis. It is not a health issue that doctors and hospitals can solve easily. For instance, they can do nothing when pharmaceutical companies flood the shelves with all the new “sleep drugs.” Weeks ago, I went to Walgreens to get some stomach relief for my partner. My jaw dropped when I saw various sleep drugs and nutrient supplements covering the multiple shelves top to bottom. Various strategies of persuasion are used in the package design—some bottles with soothing colors and joyful illustrations look like harmless gummy candies, while others appear like high-tech extracts from all-natural organic plants with exotic names.

As I delved into my research and engaged with the public through a series of events during my residency, the intricate connections between my sleep disorder and the broader socio-cultural landscape began to crystallize. As Jonathan Crary astutely observes in his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, the inexorable expansion of capitalism has rendered sleep the final frontier inhibiting perpetual consumption and production. In our relentless 24/7 society, sleep becomes an unproductive, even despised aspect of life, culminating in a global public health crisis that disproportionately affects marginalized communities, particularly those hailing from immigrant backgrounds who have historically been exploited in the United States.

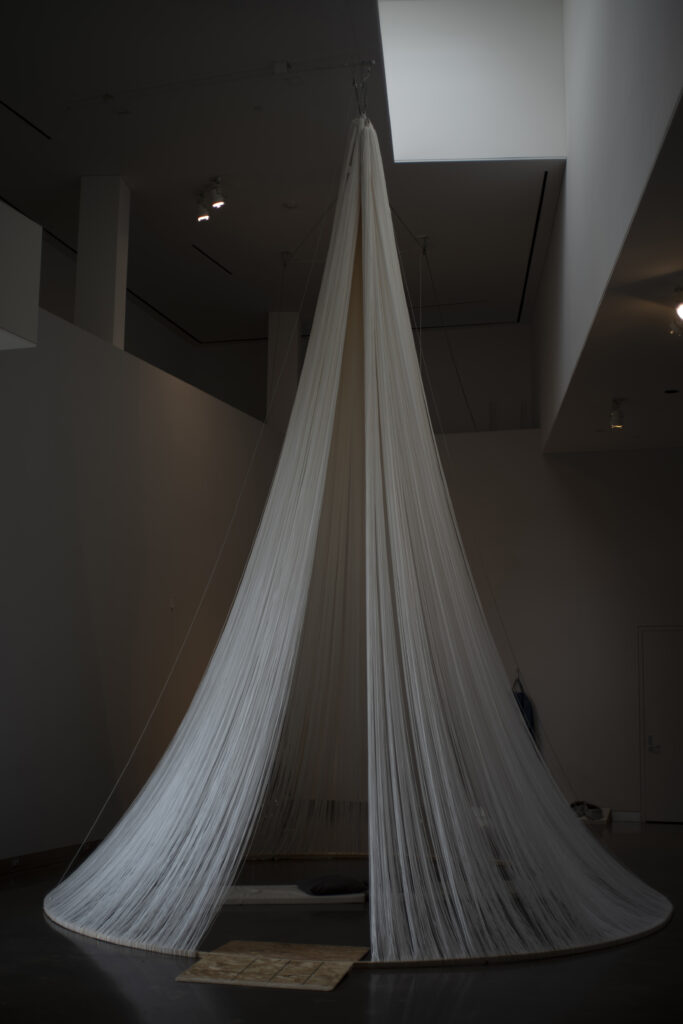

Throughout my residency, I crafted several immersive installation artworks designed to facilitate participatory events. In a departure from traditional hospital settings, I invited neurologists, psychologists, and physicians to engage in unconventional conversations with the audience in the space of my art installations. Daydream Chapel was one of the art installations I created and collectively built with soft yarn strings. The 16-foot wide, 40-foot tall installation envisions a future of healing through equitable exchanges of knowledge between healers and those seeking solace. The Daydream Chapel serves as a sanctuary where rest, breath, and wonder are revered and prioritized. Within this space, I strive to foster an environment that engenders healing, liberation, and resilience for all who share my struggles, inviting participants to explore their personal, social, and historical connections to their own experiences.

I learned how profoundly space can shape our discourse and thought processes from a few public events hosted in the space. Participants were invited to explore their personal, social, and historical connections to their own experiences, and the events fostered a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding sleep disorders. For instance, one participant shared how he sleeps better at a friend’s place and discussed the ideal home space that could give him the best sleep. He expressed his desire to live in an in-law suite at his best friend’s house. This conversation led us to reflect on how city planning and residential architecture design impact his sleep. Another participant revealed that she suffered from chronic insomnia until she married someone who sleeps really well. She described how comforting it was to sleep with someone like that and how being able to sleep together with her partner cured her insomnia. We even talked about using one’s sleep quality as a measure to find the right partner! These intimate stories illustrate the diverse factors and personal experiences that contribute to our understanding of sleep disorders.

MPMany of your projects deal with home. I’m curious how you define home, and how has that definition changed for you over the past decade?

PWIn 2017, I co-founded CarryOn Homes, a photographic storytelling project with Shunjie Yong, which aimed to collect the stories of immigrants and refugees from various cultural backgrounds making homes in Minnesota. In 2018, Zoe Cinel, Aki Shibata, and Preston Drum joined the team to form the CarryOn Homes artistic collective. Currently, the COH team is composed of Peng Wu, Shun Yong, and Zoe Cinel. Over the past six years, we’ve gathered more than 50 stories that not only reflect the suffering caused by the systemic oppression of the US immigration system, but also celebrate the joy, resilience, and wisdom of making homes on this stolen land. At the end of every interview, we always ask the participant: do you call this place home? Their answers have taught me so much what home means to our immigrants. The project has taken various art forms including large-format photography, a public art installation in downtown Minneapolis, an audio installation at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, performance, and participatory events in countless community spaces. I consider this storytelling project an essential part of the work of decolonization, involving a triangular relationship between settler colonizers, Indigenous communities, and alien labor. This framework is like a map for immigrants and refugees to find where they are in the decolonization work. But you know, a map is just a map, while art is the landscape.

My work is rooted in my search for a sense of belonging. 12 years ago, I came to the U.S. to pursue my career as an artist and seek acceptance for my queer identity. However, I found myself facing new forms of rejection. As an Asian gay man, I felt marginalized and desexualized in the predominantly white Midwest gay community, while also feeling othered in the often-traditional Chinese immigrant community due to my sexuality. I learned to comfortably talk about my queer sexuality in English. However with my mother tongue, I can’t find the acceptance of my sexuality as I am often lacking Chinese vocabulary for that. I notice, even in the middle of a conversation with friends in Chinese, I tend to shift to English when I need to talk about my sexuality.

As part of my new work for the Jerome Fellowship, I’m working on creating a series of fictitious archeological ceramic objects that tell the story of queer sexual relationships against the backdrop of Chinese transcontinental railroad workers. This work examines the relationship between colonial history, alien labor, and non-human landscapes. During my research for the project, I found when large groups of Chinese workers were brought to America to work on the railroad 160 years ago, they called themselves 金山客 guests of the gold mountain. They considered themselves guests because they never planned to call this place home. Even the majority of them left their hometown because of extreme poverty, or frequent and deadly wars. Many had families waiting for them back in their hometowns, though many never returned. I wonder what made them stay? I wonder if they eventually call this place home?

I had the privilege to choose to study abroad, hoping to pursue my dream of being an artist and search for the acceptance of my queer sexuality. After being here, I found it is more complicated than I thought. Being an Asian gay man in the U.S. feels like being at the bottom of the food chain in the dating scene. It was truly a challenge to have any sex life in the very white Minnesota around that time. This experience of being a desexualized Asian male so powerfully connected me with my ancestors—those transcontinental railroad workers. Approximately 20,000 Chinese workers worked on the railroad for many years while not being able to bring their wives. They were perceived by local Americans as not having sexual desires. They also had to engage in the traditionally female roles, such as laundry and cooking food, which contributed to Asian males being seen as feminine and sexually undesirable. Gradually this perception of the Asian male has been amplified by Hollywood movies and other pop cultures. On the other side of the coin, Asian females have been hypersexualized and objectified. These constructed stereotypes perfectly serve white supremacy. To dismantle the stereotypes, in my new project for Jerome Fellowship I mentioned above, I reimagine the history of transcontinental railroad Chinese workers from the lens of queer sexuality and gender fluidity.

My work has been exploring the skills and labor of homemaking, which is often considered women’s work. As a queer person, I embrace women’s work as part of my effort of unlearning the masculinity constructed during my time growing up in the cis-male dominated culture of China. I imagine my home in an alter-universe without gender binary construction, where colonialism, capitalism, and immigration systems are dismantled. Everyone moves freely on the planet. That’s home! Before that, every step towards the alternative universe is a moment of home. My plants and garden are my homes, and riding a scooter on the streets is my home. My mother tongue is my home. It has been a joy to identify the people I want to be with and forming a sense of community to expand that alter-universe together.

MPYou host a weekly get-together at your home of cooking and making for fellow immigrants. Could you talk about why you started this event and how has it influenced your current body of work?

PWAfter working on the sleep project for several years, I began to intentionally reject the traditional hardworking artists’ way. I already stopped actively “working” on the sleep project as I suffered greatly when I worked so hard to find an effective way to fall asleep. Anyone who has suffered from insomnia knows: the more you try to sleep, the harder it is to fall asleep. Sleep is unique in that it teaches us not to try; it forces us to tame our ambitions that may have blinded us. In Buddhism it’s called non-purposeful practice, a path to enlightenment.

I wanted to work less and rest more, embracing the idea that intentional rest is a form of active art-making. Rest is a resistance to the promises of capitalism and a rejection of being part of colonialism. The Ceramic Sunday, a queer- and Asian immigrant-centered space, started with these thoughts in mind. It’s something less like work and more focused on aimless wonder and joyful conversations with tea and snacks, which is essential in our culture. Although these conversations have never been documented, they often find their way into our handbuilt clay works. The fired clay pieces are taken home by the makers and used every day, without concern for being stolen by museums and locked in fancy glass cases. We have created small items to give to friends as birthday or wedding gifts. On these Sundays, we always start with the tea I prepare, accompanied by the snacks that guests bring. We sit and talk, unhurried and not in a rush to make anything.

Everyone gathers around a large round table, each person having a small space in front of them to create different clay objects, functional or not. Sometimes, silence envelops the room, only to be followed by the beginning of another conversation. In the end, we often order pizza or Chinese takeout. The event flows like water and keeps evolving. Just last week, a friend started practicing calligraphy in front of us, and earlier, another friend began making jewelry. We often discuss visa issues and the years we’ve spent feeling stuck in one place. But at least we’re stuck together.

MPI’ve been thinking about how the pandemic has been a life intervention, both personally and collectively. Do you have any pandemic epiphanies? Has it changed the way you approach your studio practice?

PWYes! Absolutely. I no longer have studio practice—I have dinner table practice now. I eat and make art on my dinner table with friends.

During the two years of displacement from my home during the pandemic, I thought a lot of the promises of security and progression of this place. I thought of how I was determined to make this place my home. There was so much attachment that Buddhism speaks of.

MPWhat artists/writers/thinkers have been most influential on your work?

PWIn recent years, particularly during the two years from 2019-2021 when I was unable to return to the U.S. and my home in Minnesota due to visa issues, Buddhist teachings have profoundly influenced my work. Deprived of access to my art-making facilities and the local art community, these teachings allowed me to detach from many causes of suffering and constraints, ultimately helping me to reinvent my practice.

Upon my return to the country in 2021, I developed an even deeper appreciation for our local artist, writer, and thinker community. A conversation hosted by Public Art St. Paul, featuring Wing Young Huie and Christine Baeumler, remains vivid in my memory. They discussed art-making as a durational and relational practice—two concepts that have stayed with me ever since. These ideas prompted me to contemplate how my work can center on the relationships between people, objects, and the environment, as well as the passage of time.

MPHow has winning the Jerome Fellowship affected how you approach your work?

PWBeing part of the Jerome Fellowship has been a significant moment in my artistic journey. Ideally, it will enable me to work less and rest more—an act of decolonization, considering the extent to which alien labor has been exploited for the sake of “progression” from a colonizer’s perspective. Additionally, I hope to inspire others like myself to work less and rest more, thereby contributing to the “lay flat” or 躺平 movement initiated in China, which may become a global movement shifting our energy from the blind progression to intentional rest.

MPIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

PWThe phrase “应无所住,而生其心” can be translated to English as, “One should not abide anywhere and give rise to the mind.” It is a quote from the Diamond Sutra, a Buddhist scripture, and it conveys the idea that one should not become attached to any particular thoughts, concepts, or ideas, but instead remain open, unattached, and flexible in their thinking. What’s interesting is if I translate the text literally, it can also say: “One should not have a place to live, which give rise to the mind.” That’s quite inspiring for immigrants like me, who often struggle with having the certainty of residency. The non-attachment to one place of residency can be exactly the right place for one’s mind to call home and find rest at. So I am going to choose the word 无所住.