Steve Ozone: The Story Behind the Lens

On perseverance over the span of a creative life: striking out on new paths, making the best of the opportunities that come, and observing how others navigate life

“History matters. Narrative matters. It matters in life, it matters in history. There’s a story. And that’s what we can grab onto. Human beings sitting around the campfire millions of years ago wanted the story. That gives us order. It gives us moral code, it gives us a sense of place, a sense of belonging. It fills a lot of needs.”

John Kremer, co-owner of the California Building

In the Traffic Zone Building located in the North Loop in Minneapolis, photographer Steve Ozone sits down with a fizzy drink and a bowl of grapes at a small table in the middle of his dark studio. Like most photographers, he is more comfortable behind the lens, and asked if I could wait to take his photo, noting that he needs a haircut and a beard trim as he runs his hands through his salt and pepper hair. All around him, he is surrounded by gathered fragments of past projects and work, lovingly saved to prevent being thrown in a landfill. His speaking cadence via his gravelly voice is thoughtful, and comes in short spurts as his brain tumbles through his thoughts to get out the right words. The conversation is often punctuated with a smile and exclamations of, “Wait, don’t put that in there,” as he speaks.

In the hallway between artist studios hang newspapers from the early days of the pandemic that Ozone saved. He also saved any masks that littered the streets. His intention is to create an installation with the two components, but a lot of details still need to be hammered out. A lot of Steve’s work falls along those lines: there’s no need to ask, nor is there a need to have all of the details prepped. Just start doing; the rest will work itself out.

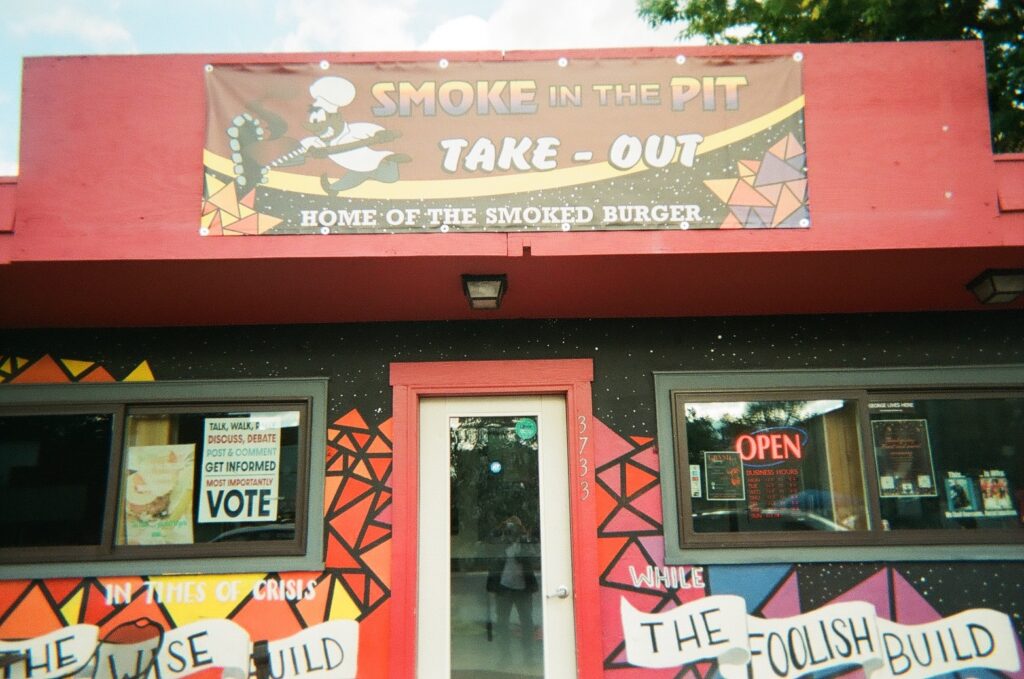

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

He most likely got that sensibility from his paternal grandfather. “I never got the chance to talk to my grandfather about his immigration story, but fortunately for our family, he wrote a book about his experiences.” Ozone says. “He came to the United States in 1906 from Japan. After working in China, he wrote a letter to his boss and said, ‘I’m sorry I have to leave my job. For me to become a proper gentleman, I feel I need to move to the United States.’ He was a dreamer, and he was single. He wanted to come here because everybody thought the roads were paved with gold. I don’t think he necessarily thought he was going to get rich, but he was thinking of it as a new land and a new adventure.”

In 1906, his grandfather ended up going to Alaska, before Alaska was even a state. When he finally came to San Francisco, he had to stay on the boat in the bay for two days because there wasn’t enough room to dock. “He’s sitting on the boat looking out at the city that he’d traveled so far to get to, and he couldn’t step foot in the city. When they finally docked, he looked around and saw the city was in rubble, because it was a month after the San Francisco earthquake.”

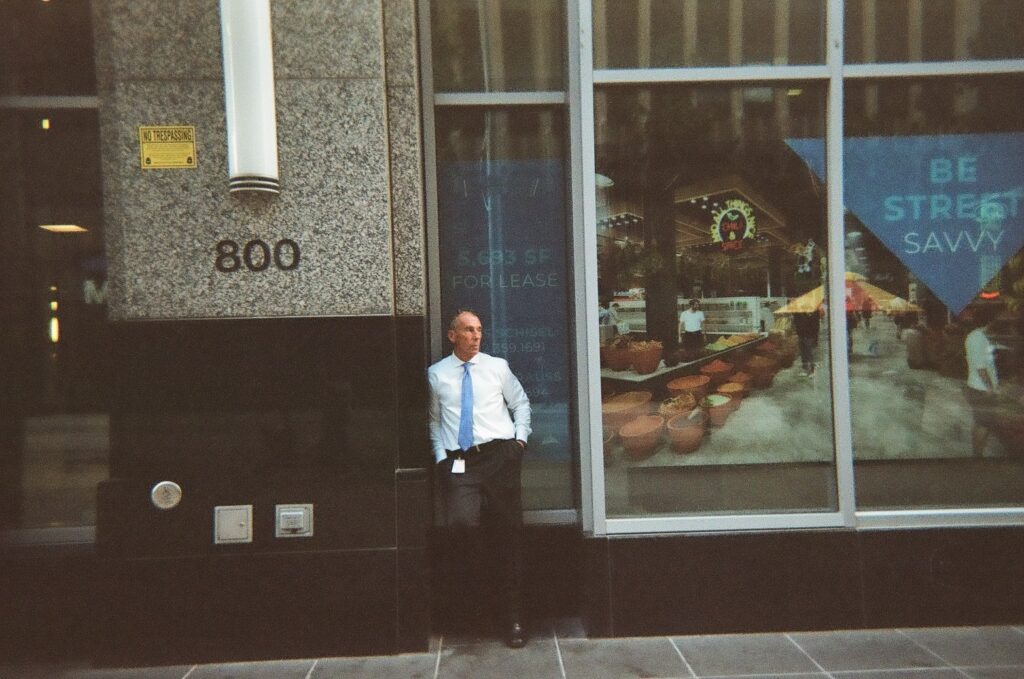

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Steve, too, took off on his own as a young man, and created his own story by seeking a job in journalism in a big city. It led him to Florida by way of Detroit. He had dreamed of working for a newspaper and applied at a few publications, but no one took the bait. He ended up doing high school portraits for a little company in Detroit that had a branch in Florida. The company sent him to Florida for a year, and he tried to find creativity in the work he was doing. He shares, “I was shooting for the high school band marching band, and it got to where it was so mechanical. There was no room for creativity, but at the time it didn’t bother me because it was my first job. I didn’t know any better. Now that I look back on it, it was good experience to learn how to be a better photographer. This is what I’m grateful for in that job. Because it was so boring, I made a game where I would photograph a student in the morning, memorize their name, and then repeat it back. If I ever saw them again, I would be able to remember their name. I think I got pretty good at it because nobody ever corrected me. I’m still pretty good with names, but if it’s an uncommon name, it takes me a while.”

When the year was over, the photography company eventually closed its Florida branch and had Steve get the equipment back to Michigan, something he suspected was his main purpose in being in Florida. He moved back to Detroit to work for the company for another two years before finding work in a dark room for a department store. The store ultimately had Steve and his colleagues migrate to the Twin Cities, where they spent time shooting ad campaigns for Dayton-Hudson Corporation.

As he talks, he pulls out the ads he saved from his time as a photo assistant, lovingly stored in folders for posterity. Ozone gradually moved back into shooting portraits. This time he collected stories of the people he was documenting. What he found were tales that would have been lost had they not been collected. When his cousin Bill Kubota approached him about doing a documentary on a documentary, Ozone came full circle with storytelling. Their collaboration, a film called The Registry, tells some of the stories of 7,000 Japanese language students stationed at Fort Snelling during World War II. They served all over the Pacific, but little was known about the role Japanese Americans played in the Military Intelligence Service. These young men were recruited from internment camps to help in the war effort while their families, who had lost everything through this imprisonment, were being treated like war criminals simply because they were of Japanese descent. While doing sound and some camera work, Ozone found himself asking questions of his subjects to tell their largely unknown story.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

As a documentarian, Ozone’s personal experiences give way to many other stories, and he becomes the medium through which they pass. Growing up in a household in Rochester, New York with a Chinese mother and a Japanese father, he learned the ways of the world through others’ eyes again, and gradually realized it was also his story. He says, “My family was in internment camps during World War II. We didn’t learn Chinese or Japanese growing up. My parents wanted us to assimilate because they had gone through so much prejudice. They didn’t want us to go through the same thing, but it was such a loss for us. We would have resisted, because there wasn’t a community where you could feel more comfortable being Asian. We were just plopped down in the middle of a bunch of white people. I didn’t think anything of the racism we experienced at that time, but now that I look back there were a lot of microaggressions that I missed.”

He has found a way to extend his work into different mediums, be it videography or documentaries or the large mural that depicts Minnesota immigrants which faces the connector skyway at MSP Airport. His lens is constantly moving to new subjects and finding new stories. Over the years, his work and techniques have evolved. Within the last decade, he gravitated to using simple backdrops to focus on his subjects when doing portraits. He found using a blank, white backdrop to capture his subjects in a different manner allowed their stories to extend to any geography. He still draws on the traditional rules of portraiture, but he’s gravitated towards natural light, having his subjects stand naturally, and he uses non-studio settings. Although photography has been his primary medium, he’s finding he’s a collector of stories. Through his empathy, Steve quietly finds his way into other’s lives. He sees the overarching story and understands the minutiae of why we do things, then he pulls back the view of the lens to see the bigger picture.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.

Photo: Steve Ozone.