掩耳到零 Cover Your Ears and Count to 0

A letter to a friend across national borders: a missive of love and speech without shame that considers censorship, longing, and translations that only diasporic ears can detect

Dear Chris,

At the time of finishing this writing, I broke into a long period of wailing, outside on a porch, near a lake that used to have a name of a slavery apologist, in Minneapolis where we first met. I had just read your writing,1 you and your mother on strange lands, and your father’s absence, and our dots intersected amidst these nonlinear times. It was about to storm, the wind was heavy with sorrow. I hope it rains for a long while, to hold memorials with all the hungry and shameless ghosts.

亲爱的Chris,

在这篇文章快结束前,我坐在阳台上嚎啕大哭了一场。我家附近有一片湖,它之前的名字取自一个拥护奴隶制的副总统。我还住在我们相遇时的双子城。刚读了你的文章 1,你讲到你和你母亲在异地的境遇,你父亲的缺席,还有我们在非线性的时空中交织连结。暴雨要来了,风像哀愁一样重。我希望雨可以下很久,以此祭奠那些饥渴又无耻的幽灵。

In the essay “Speechless Shame and Shameless Speech,”2 Lewis Hyde writes that, “children who live in two worlds are vulnerable to several shames, several sets of eyes watching them.” I wonder how this has applied to us.

在“无言的羞耻和无耻的表达”2一文中,路易斯·海德写到,“生活在两个世界的孩子们要面对几种不同的羞耻,被好几双眼睛盯着。”不知道这句话是如何在我们身上得到验证的。

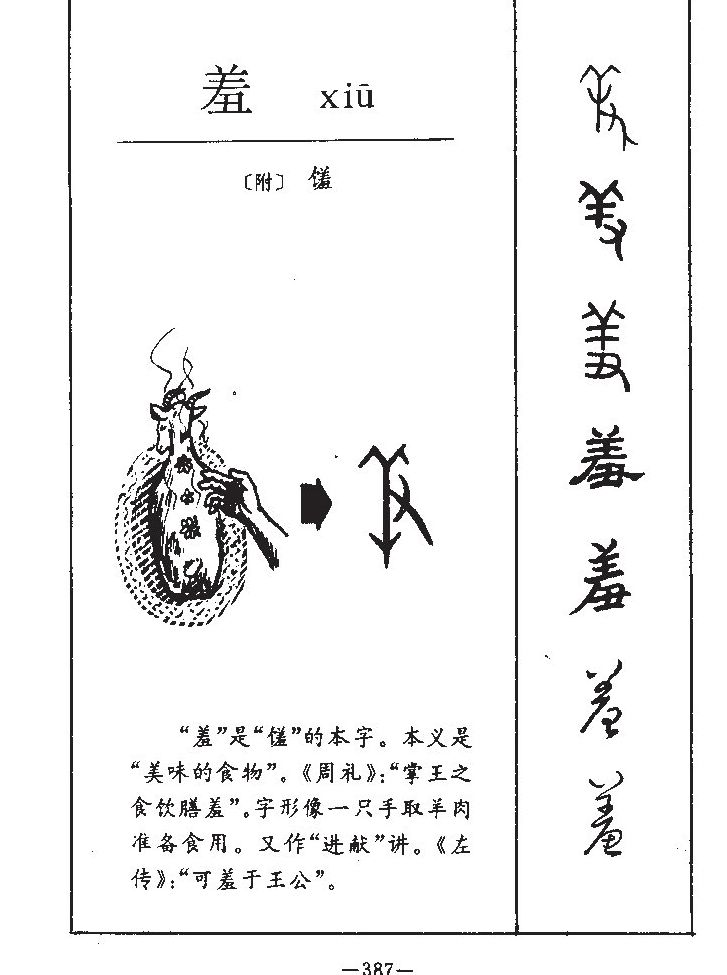

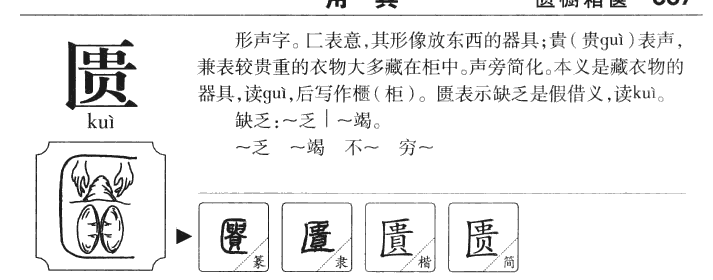

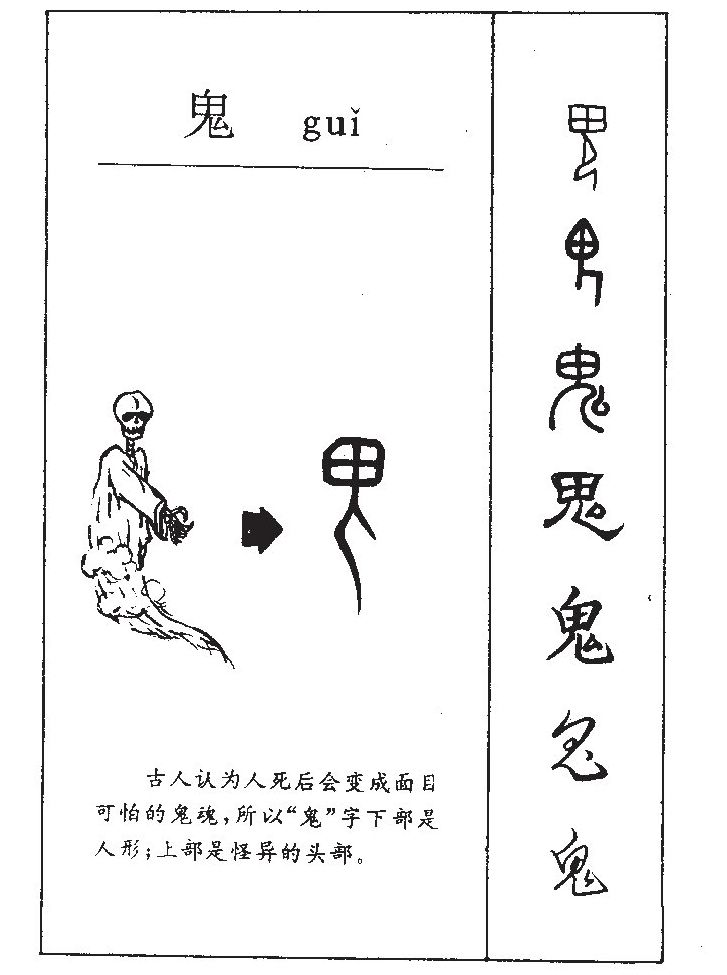

“Ashamed” in Hanzi is “羞愧.” “羞” can mean both “a delicious lamb offering,” and also “ashamed.” “愧,” by looking at its components, “忄” evolves from “心,” which means the heart, “忄” is like a standing heart. The characters that are accompanied with it usually describe interior thoughts. “鬼” is “ghost,” “shadow,” “spirit,” “demon” or “devil.” In the phrase “鬼子,” it is used as a pejorative slur for “Japanese imperialism or Western power,” which evolves postwar to carry xenophobic connotations as “foreigners.” “愧” relates to the meaning of “shame,” and literally looks like “shadows casting on the heart” to me. Shadows are cast by light. That means to examine shame, one ought to examine the light source and what’s in the way of light.

“Ashamed”在汉字里写做“羞愧”。“羞”还有一层意思是美味的羊肉贡品。乍一看“愧”字, 竖心旁来自“心”字的演变,竖心即是一颗站立的心脏,和其他的汉字搭配使用,通常用来形容丰富的心理活动。“鬼”字便指“灵”,“阴影”,“灵魂”,“妖魔鬼怪”。“鬼子”这个词用来讽刺日本帝国主义和西方势力,在战后便承载了仇外的含义。“愧”用来形容“羞耻”,字面上看起来像是“心上长了片阴影”。阴影是由光投射形成的。所以说,我们在讨论羞耻的时候,其实是在讨论光源的出处,究竟是什么挡住了光。

Chris, what do you think is in the way of our light and our right to opacity?3 Is speaking from a place of shamelessness an attempt to queering our identities and escape from the coherent archives? Aren’t we borrowing tools from psychopaths?4

Chris, 你觉得是什么挡住了我们的光?又是什么拦截了我们坚持浑浊的权利?3 采取一种无耻的态度来表达是不是在推翻身份的稳定性, 从字正腔圆的叙事中逃脱出来。如果是这样的话,我们算不算是在佯装反社会人格。4

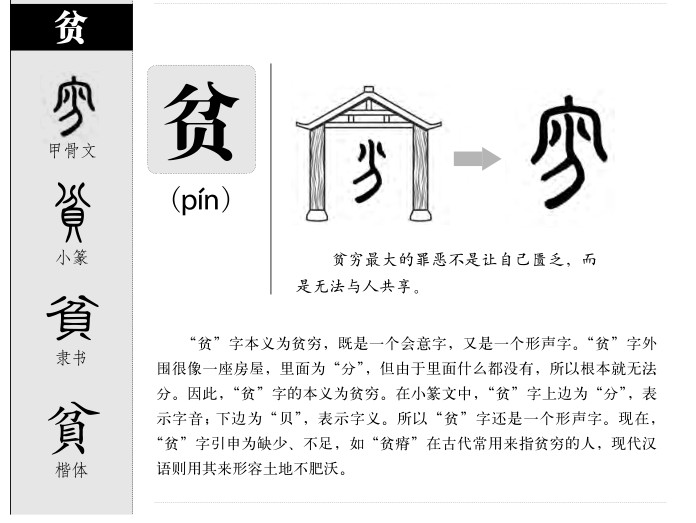

“Lack” in Hanzi is “匮乏.” “匮” looks like “贵” in a half-enclosed container: “匚.” So the “lack” is not about being short of something. The container is not empty; it has something valuable and expensive in it, which is what “贵” refers to. This alters the light source of “lack” for me. In this sense, the feeling of “lack” is about the inability to protect the valuable thing you already have, and less about not owning that valuable thing to begin with. It’s about boundaries and what enables healthy sharing. The word “贫,” which refers to “poverty,” stems from the notion that lacking in oneself is not the worst sin, but the inability to share with others is true poverty. Both “lack” and “poverty” involve the quality of sharing. What can be too much to share?

“Lack”在汉字里是“匮乏”。“匮”字看起来像是“贵”字被装在一个半开放式的盒子里:“匚”。所以“匮乏”不光是指缺失了什么。盒子并不是空的,它里面放着价值贵重的东西。这种角度改变了我对匮乏的认知。原来“匮乏”的感觉更像是无力保护你觉得有价值的东西,并不仅是你原本就不拥有它。这是一个关于界限的课题,是什么保证了良性的分享和给予,以至于不自我压榨掏空。在一个配图的字典上找到“贫穷”的“贫”,有一个解释让我惊讶:自我的匮乏并不是十恶不赦的,而是无法与他人分享才是真正的贫穷。“匮乏”和“贫穷”都包含了分享的质量。那有没有无法承受的分享?

“Shame.”

“Lack.”

“Ghost.”

“Poverty.”

Our friend X got her period today, but it was already delayed due to contracting COVID. She was in much pain, and told me her Wechat feed blew up with horrendous news that could swallow one up entirely. She said that they are testing people’s submissiveness and bottom line every day.

X今天来月经了,新冠康复后推迟了经期,疼痛难忍,然后看到微信上的水深火热更让人不能自拔,她说那里每天都在试探人们的奴性和底线。

All of a sudden, my ears rang the first line of the Chinese national anthem: “Get up, people who won’t submit to slavery.”

突然想起中国的国歌第一句是:起来,不愿做奴隶的人们。

A cell phone footage went viral online, and made its way to The Daily Show in liberal American media. But Trevor Noah’s team still missed the most key translations that only diasporic ears can detect. They only mentioned that the drone played recordings to stop people from opening their windows and chanting. But Mandarin-speaking friends around me were surprised by the poeticism in this one sentence: “Supress your soul’s longing for freedom.” So the government admits that souls and freedom both exist, and they will sacrifice them readily.

有一个手机视频在网络上疯传,没出几天就上了Daily Show, 但是Trevor Noah的团队还是漏掉了一个很关键的翻译。他们只讲到有无人机会播放让人们不要开窗歌唱的录音,但是我身边懂中文的朋友都说“控制灵魂对自由的渴望”这句话十分诗意。所以政府是承认灵魂和自由都存在的, 而它们会被不惜一切代价地牺牲掉。

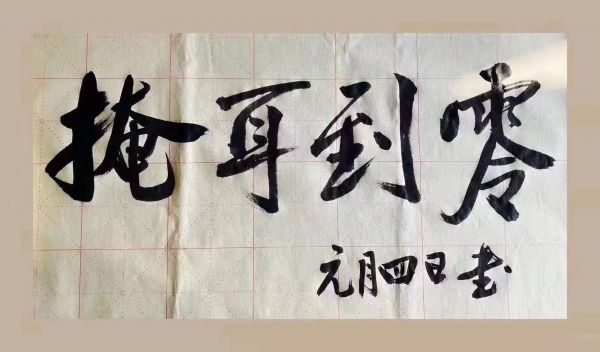

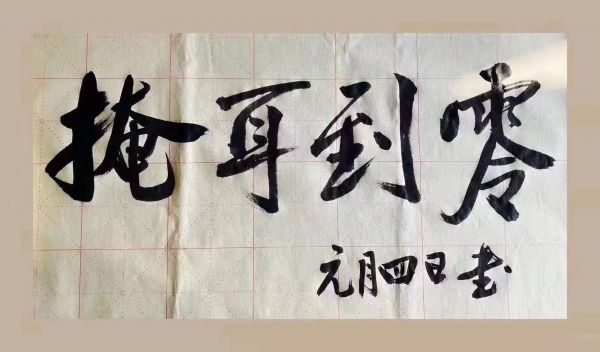

My friend P passed me some research5 that talks about the cultural tension between simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese characters in the regions of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and Mainland China. In simplified Chinese, the character for love (爱) is missing the heart (心) inside it, and replaced by friendship (友). Both groups mock each other for “lacking something.” Morals, history, sophistication, accessibility—language evolution becomes a way to trace the historical turns of political and cultural shifts. The censored words can be made missing like ordinary lives, but they can shapeshift, change sounds, and try on new formations and new translations. The phrase “掩耳盗铃” is substituted by “掩耳到零” during the enforcement of “zero-COVID strategy.” The original phrase is a story about a thief covering up his own ears while stealing a bell, thinking no one would hear him if he himself can’t hear the bell. The evolved phrase is used to call out the entire corrupted political system that executes orders aggressively to clear COVID cases.

朋友P介绍给我一个关于简体中文和繁体中文之间的斗争 5,尤其是在台湾,香港,新加坡,马来西亚,还有中国大陆等地区中。在简体中文里,“爱”这个字没有“心”字在其中,而是被替换成“友”字。两大派系都指控彼此缺乏文化底蕴,道德,历史,普及性——文字成为了一种探究政治变迁和文化更替的风向标。被屏蔽或删除的词语就像被迫消失的人命一样,但是它们会变身,变声,形成新的符号和翻译语境。在“清零政策”的执行下,“掩耳盗铃”被网友巧妙地替换成“掩耳到零”。成语本身是在讽刺一个自欺欺人的偷铃铛的贼,他以为把自己的耳朵掩盖住了,别人就也无法听到铃铛的响声,可以“毫无声响”地作案。在新冠的背景下,这个成语被用来抨击整个腐败的政治体系,为了“社会面清零”而藐视公民权益。

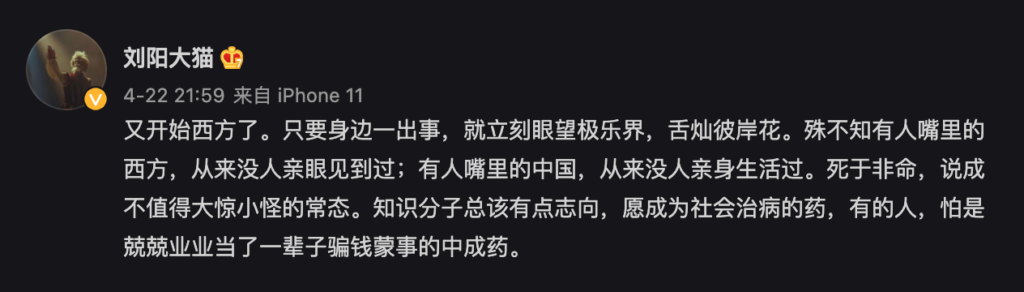

A party associate and commentator from the Global Times whose name sounds like “To Purify Restlessly,”6 spilling nationalistic and patronizing perspectives, used phrases like “desensitize reactionary collisions in the process of execution” and “protect a dynamic stability and balance” to support censorship and erasing citizen-generated documentations. The man with the name that sounds like “To Purify Restlessly” got his share of being canceled7 by the machine: his censorship privileges didn’t shield him for too long after he cautioned Beijing to steer away from the costly “zero-COVID strategy.”

有一个驻环球时报的评论员,名字听起来像胡洗净(to purify restlessly),6一贯他传统直男的笔锋,用了“对治理中的摩擦需要脱敏”和”维护动态的稳定与平衡”这些字眼来支持删帖删视频。那为什么中文互联网有那么多”敏感字眼”,是不是可以建议他们需要脱敏?对了,他们把那个叫做”和谐”。胡洗净一直在享受审查特权,但是在北京继上海后也将面临“清零政策”的镰刀时,他发表了篇批评,7便也迎来了被审查机器拦截的下场。

I found a blog user’s comments amusing on the writing of “To Purify Restlessly”. It reads: “He’s talking about the West again. Once something local happens, he looks towards La La Land as if he’s from there and knows all about it. Some people talk about the West, but they have never been there; some people talk about China, but they have no lived experiences there. Unnatural deaths become normalized by these people. Intellectuals ought to have some ambitions to serve as medicine for society, but some people are loyal for their entire life to serve as over-the-counter scammers.”

“I have spent much of my life turning away from the scripts given to me, in China and in America,”8 Yiyun Li writes in Dear Friend, “my refusal to be defined by the will of others is my one and only political statement.” Dear Chris, I find some refuge in her statement because we also suffer from non-consensual close-readings of our humanities. In the box of human identities such as, immigrant, Chinese in diaspora, East Asian, some also assume I am Asian American. It requires a second look to tell apart Chinese pro-Trump supporters from Chinese Americans who fled China from political backlash, from Chinese ultranationalists who hold foreign passports, and even from Maoists who mark themselves by the position of powerlessness.9 Technically, we are all a part of the Chinese Diaspora.10

“我用了人生很大的精力去回避强加于我的来自中国和美国的脚本, 8”李翊云在散文中写到,“我拒绝被他人的意志所定义,这也许是我唯一的政治立场。” 亲爱的Chris, 我从她的这句话中找到一种庇护,也许我们都要承受同样的不征求我们同意的,各种解读的窥视。在人类身份的条条框框中,我有着移民,海外华裔,东亚人的标签,有些人也会认为我是亚裔美国人。如果不花时间鉴别,很少有机会从支持川普的中国人中挑出很早就因为政变而背井离乡的华裔美国人,还有那些拿着非中国护照的中国极端民粹主义者, 或者从他们中挑出热爱用被压迫者的身份来定义自身的毛泽东主义者。9 在某种程度上,我们都被囊括进“海外华裔”的标签。10

In Nanfu Wang’s 2021 documentary In the Same Breath (streaming on HBO Max), she takes a personal journey to investigate the mishandling of the pandemic, both in China and in the United States. Departing from the cliche polarizing comparisons of the East vs. the West, censorship vs. freedom of speech, political prosecution vs. human rights, she underlined similar gimmicks that the two governments used to produce propaganda in order to assert their stories of triumph as the national narrative. For China, the story is about the smallest number of positive cases. For the U.S., the story is about the largest percentage of a vaccinated population nationally. Both stories are not about the citizens of these nation-states. They are about supremacy, international influence, and the melodramatic hero’s journey.

2021年,王男袱的纪录片“同呼吸” (在HBO Max上独家播放),她以自己的视角去审视中国和美国在新冠疫情时的应对过失。不同于“对比东西方视角”的陈词滥调,审查制度和言论自由的两级对照,政治迫害和维护人权的对立叙事,她强调了两个政府在宣传胜利叙事和官方叙事上运用的大同小异的伎俩。对于中国来说,故事主线围绕着最少的感染人数。而对于美国而言,故事的另一个版本是接种疫苗的本土人数。两种故事都与两国的公民无关。而是关于极权,国际影响,还有英雄之旅。

My housemates jumped on a video call with some friends from Shanghai amidst the lockdown. They are a couple. They talked about a discussion channel on immigrating to the U.S. Because of my mother’s bold decision to leave China in the 90s 11 and immigrating to the U.S. after almost leaving it entirely, I hadn’t needed to worry about visas. I am not very familiar with the different types of visas that shape many of my friends’ daily life choices and career moves. The couple wanted to research immigration policies in different countries to prepare for a plan B. I restrained my desire to share more complexities. Regardless of the reasons that cause one to consider immigration, migration is an act of agency, like how my mother needed to uproot in order to have her own life. Facing Asian hate in America is yet inconceivable to her. Settling on stolen land is not a part of her consciousness. She never foresaw that the requirement of participating in the American dream is to whitewash her cultural preferences, and this act of never-ending assimilation still doesn’t secure her employment because somebody felt uncomfortable listening to her accented English. It wasn’t my place to tell the couple that immigrants are also settlers.12 What is receiving them is another system’s injustice not far from their own. Our hands are full of blood. Everywhere. It’s not possible to discern another’s blood from our own.

我的室友们连线了经历了上海封城的朋友。是一对情侣,我不认识。他们说最近看了一个讲移民美国的直播。我母亲90年代就单枪匹马地出来闯美国, 11在差点回国的境遇下好不容易站住了脚跟。我之所以从来不用担心在美国的身份问题,都得益于我的母亲。这便使我对签证的种类模棱两可。这对情侣表明就是想研究一下各国的政策,给自己一个后路。但是我忍着没有说太多我内心的五味杂陈。无论是以什么原因移民,人们从来都是把另外一边的草看成是一条出路和梦。就像我母亲当年。她想象不出自己以后居然会面对强烈的反华情绪,不知道自己踏上的是被屠杀掠夺来的土地,更不明白为了美国梦而极力洗白自己的文化和思想是一个多么不停内耗的过程,却还是会因为浓重的口音而被拒绝了工作机会。我不想在这对情侣面临压迫的窘迫时刻,告诉他们移民者也可以是定居殖民者, 12迎接移民者的也可以是另外一个制度下的不公。我们的双手,到哪里都沾满了鲜血。已经认不出来是别人的血,还是自己的血。