Violence Within // Violence Without

Mn Artists guest editor Christina Schmid introduces an upcoming series of articles examining the subtle and symbolic manifestations of violence that pervade contemporary life, and the artists who not only make such violent structures visible but suggest practices to reconfigure violence into something else.

Flip-flops, jeans, T-shirts and hoodies in shades of blue litter the gallery floor, washed up like so many bodies: Kader Attia’s La Mer Morte (The Dead Sea) (2015), currently on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, remembers those desperate and brave enough to attempt crossing the Mediterranean’s perilous waters. A history of violence embodied in shed garments that no longer shelter bodies.

On February 14, 2020, a group of protesters face freezing temperatures in Minneapolis to march for missing and murdered indigenous women: an epidemic of violent disappearances that so far has failed to incite political will and public outrage for making change. Some of the banners feature a red dress, a motif inspired by artist Jaime Black’s REDress project that honors and advocates for the disappeared.

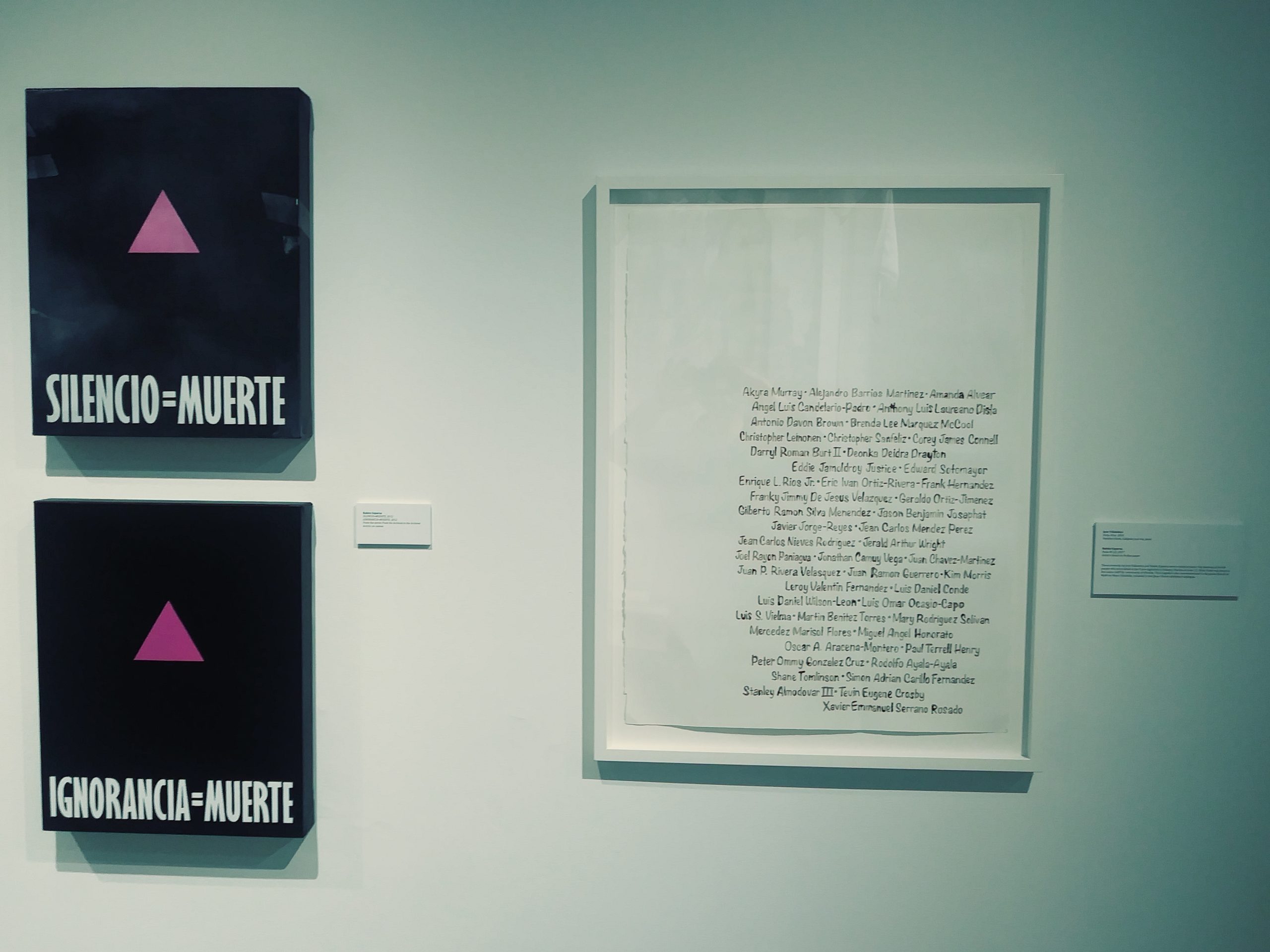

A brief list of exhibitions on view in fall 2019 in the Twin Cities reveal one connecting thread: violence. A grid of faces stenciled in mud slowly wears away under visitors’ feet. Portraits of killed Mexican journalists suffer a slow erasure, an act haunted by stories of lives lost to violence. At The White Page, Tia-Simone Gardner presents an oversize upright compass stretched in black velvet: an instrument to chart the violence of the Middle Passage and orientate the accumulation of wealth in this country to its brutal roots. A litany of names written in Rubén Esparza’s blood commemorates the victims of the shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Trash pulled from a Minneapolis lake, sorted into a disturbing catalogue of indifference, makes visible the casual disregard for other species, living bodies of water, and each other: a mundane violence, so ordinary it fails to register as violence. (The list could go on. The list does go on.)

-preferring-death-to-such-a-life-of-misery-somehow-made-t.jpg)

countrymen who were chained together, (I was near them at the time)

preferring

death to such a life of misery somehow made through the nettings and jumped

into the sea (2019). Image courtesy of the artist.

Art and violence are no strangers. From outcry to critique, complicity to commemoration, artists grapple with the presence of violence in our midst. Far from being nonsensical, barbaric, or a problem conveniently relegated to distant parts of the globe, violence is here and now, symbolic, physical, felt.

Rather than focus on acute eruptions of violence, the series of texts to follow considers the systemic, cultural, administrative, institutional, and relational processes so ubiquitous and cloaked in narratives of common sense that they make and mask violence as ineliminable.

Arthur Kleinman writes, “Instead of viewing violence, then, simply as a set of discrete events … the perspective I am advancing seeks to unearth those entrenched processes of ordering the social world and making (or realizing) culture that themselves are forms of violence: violence that is multiple, mundane, and perhaps all the more fundamental since it is hidden or secret violence out of which images of people are shaped, experiences of groups are coerced, and agency itself is engendered” (239).

The forms of violence we let take root inside of us pave the way for accepting violence without.

Some violations arrive in symbolic form. A history left untold; a point of view shunned into wounded silence. A transgender student tells me about filling out forms that only provide two boxes, one labeled M, the other F. There is no place for them on this binary map of gender identity. A life erased, an experience invalidated. Artist Xandra Ibarra, when asked to “identify identity” and its role in her practice, excoriates the “protocol of obedience” institutions enforce to get brown bodies, queer bodies, immigrant bodies to perform Otherness for the edification of predominantly white audiences. Bureaucratic systems rely on a perceived scarcity of resources to instill compliance, to coerce experiences, while celebrating their putative inclusivity. The goal: to make subjects feel indifferent about not only others’ suffering but their own. Symbolic forms of violence are naturalized, normalized, and thus effectively masked.

So, what violations have we come to accept to the point where we no longer consciously feel them? What violence do we inflict on ourselves daily as part of a regime of common sense, so ordinary we no longer even recognize its capacity to inflict wounds visible and invisible to the naked eye? What does such tacit acceptance mean for the potential to undo, transform, and heal from systemic violence? The point of this inquiry is not to rank one form of violence as worse than another, pit one history of trauma against the next, but to ask where and how art can make visible the underlying structures of violence. Once available to perception, can we intervene in these structures and processes? Can we opt out? And what are the risks inherent in such choices?

In The Topology of Violence, philosopher Byung-Chul Han takes a long view of violence. Societies have long relied on violence to keep people in line. Once upon a time, the sovereign held the power of life and death, demonstrating his power in public executions. Violence was a spectacle, out for everyone to see as a dispassionate display of power. Fast forward to the early European republics where the distribution of power changed: Foucault’s Discipline & Punish chronicles the transformation of the social sphere into a carceral structure, a panopticon where individuals police each other through constant surveillance. You are never not being watched. In this model of social organization, violence creeps closer: the omnipresent gaze demands repression of all that is criminal or simply improper. But repression comes at a price: Han links Foucault’s panopticism to Freud’s psychoanalysis. Repression demands we violate ourselves, an internalized violence that manifests in neuroses and psychoses.

Though the repressive paradigm lingers today, the times have changed. Yes, surveillance is everywhere, but we also routinely volunteer our data online. “Repression” may sound quite quaint in the darker corners of the internet. Privacy itself has become suspect in the age of transparency: surely, you must have something untoward to hide if you are interested in having your privacy respected. On social media, we perform perfect lives, outperforming each other and our old selves one status update at a time. In 2008, art theorist Jan Verwoert ended his essay “Exhaustion and Exuberance” by asking, “If, living under the pressure to perform, we begin to see a state of exhaustion as a horizon of collective experience, could we then understand this experience as the point of departure for the formation of a particular form of solidarity?” Then, the pressure to perform seemed a symptom of the precariat; now, it is everywhere.

According to Han, we live in a society of achievement: we capitalize on our resources, maximize our talents, and relentlessly use the language of economy to understand who we are, what we do, and how we relate to each other. Like stocks, we perform. We pass judgment on others, and ourselves, based on a toxic meritocracy that measures human worth in economic terms. Social Darwinism meets neoliberal capitalism. Self-exploitation is the name of the game. The violence that this way of thinking and living inflicts on us is considerable and comes with its very own set of psychopathologies. Han lists burnout, shame, depression, and omnipresent anxiety.

Conceptualized like this, “the social orders in which we move, perceive, and act are themselves violent,” writes Michael Staudigl. “This violence of irretrievably contingent orders is in no sense a sign of their dysfunctionality—rather it is essentially constitutive of them” (45). Violence and the threat thereof make sense: that is, they produce meaning. But they do so in clandestine ways. Staudigl’s point: “We need to understand violence against the other in relation to the silently imposed and habitualized ways in which we are used to dealing with our own vulnerability” (54). We pretend to be inviolable to mask our very own capacity to experience injury. Some pretenses come at a cost. Some masks may reveal more than they hide. A self-inflicted injury is still a wound.

Why explore these ideas through art and in the words of artists?

Like violence, art too operates in the symbolic and the somatic simultaneously. Art engages not just the intellect but the mind-body in all its capacities. And art has a long history of trying to make the invisible visible. Art probes spaces “beneath” language, in excess of what any system of signification can hold. (Language parses the world in more and less violent cuts and divisions.) Art may offer a platform to speculate on what happens when “the taken-for-grantedness of factual normative orders turns brittle and collapses.” What kinds of “‘wild spaces of experience” become available then? (49) Wild could mean gentle. Could mean slow. Could mean tender. Could mean joy.

From adrienne maree brown’s pleasure activism to Peng Wu’s Art of Sleep and Tricia Hersey’s Nap Ministry designed to preach opposition to “grind culture,” artists are finding ways to reconfigure the violence within into something else. A something that isn’t a thing, but a practice that may allow for making visible options beyond compliance and exhaustion: rest, maybe. Catharsis. Convalescence. Or transformation: Nicholas Galanin hacks to shreds an industrially produced faux Tlingit mask before gluing together the wood shards to form a new mask. Between purge and ceremony, new rituals imagine untested gestures of resistance and, perhaps, reconciliation.