A Conversation with Scott McCloud

Best known for his inventive webcomics and landmark nonfiction works - "Understanding Comics," "Making Comics," Reinventing Comics" - Scott McCloud has just released his first book-length graphic novel, "The Sculptor." But it's a story he's been working on for half his life.

Pinning down a singular role for Scott McCloud in the comics world just keeps getting trickier. His development as the writer/artist auteur of the ’80s Eclipse Comics series, Zot!, put him in good company during the era’s indie boom; even if that’s where it ended, he’d still be held up as a cult hero. But his role as a creator of serial fiction soon expanded dramatically with a series of statements, ideas, and theories that have put him at the forefront of comics and helped to define the work as both a unique form of art and a means for independent expression.

McCloud was the principal author of the “Creators’ Bill of Rights,” a document that pushed for autonomy, proper credit, and contractual fairness for comics creators. Though its impact on the circa-’90s industry has been downplayed, its issues have never been more relevant to the current generation of independent artists making their way on the internet and through crowdfunding. His comics-theory trifecta, Understanding Comics, Reinventing Comics, and Making Comics, are essential texts for anyone interested in figuring out the visual language of the form — and how far that language can be stretched in the service of current technologies and cross-cultural ideas. And as the originator of the 24-hour comic — a challenge for artists to create and complete a 24-page comic in a continuous 24-hour span — he’s given rise to one of the most beloved traditions in contemporary comics, a catalyst for breaking blocks and spurring new ways of working.

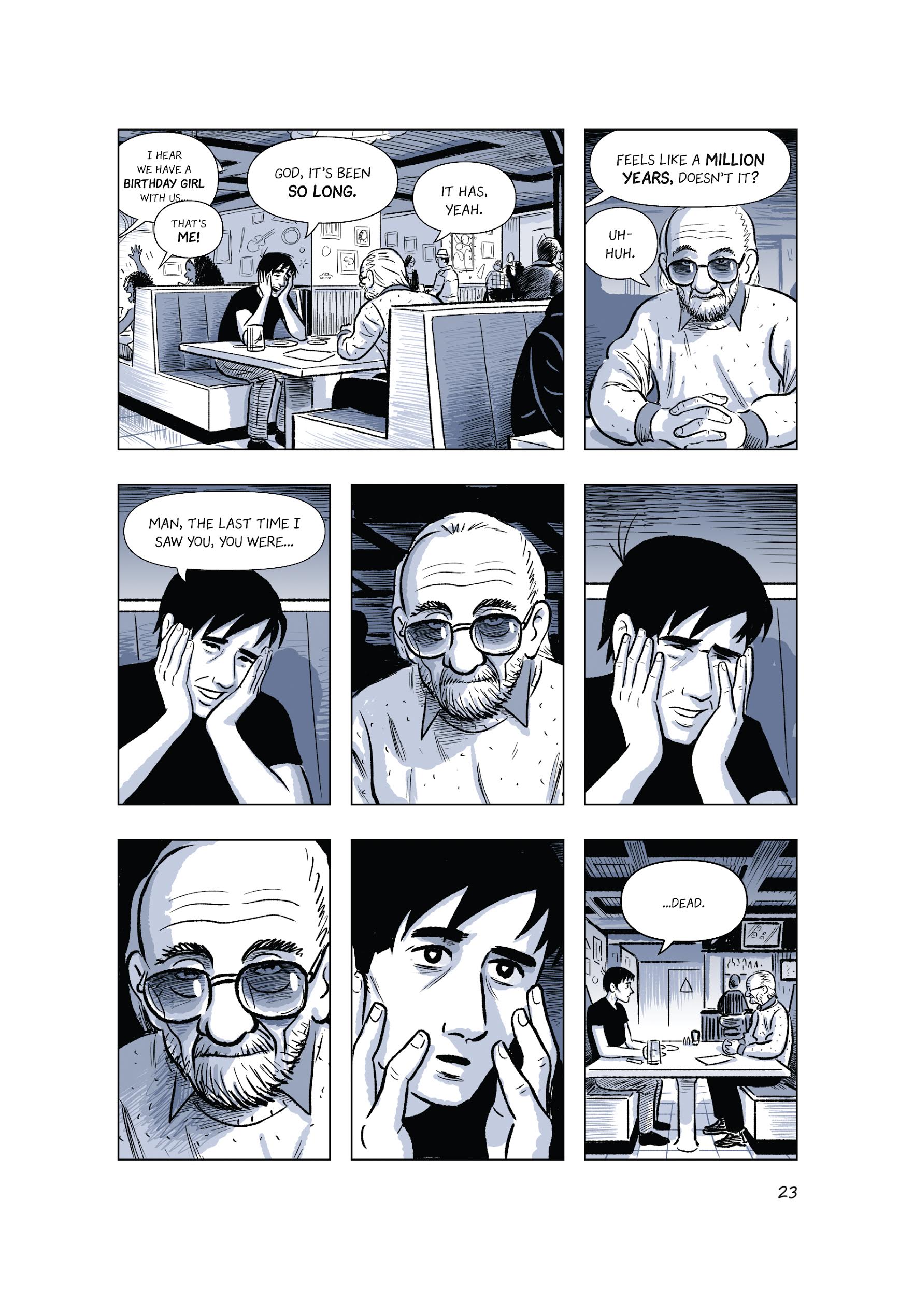

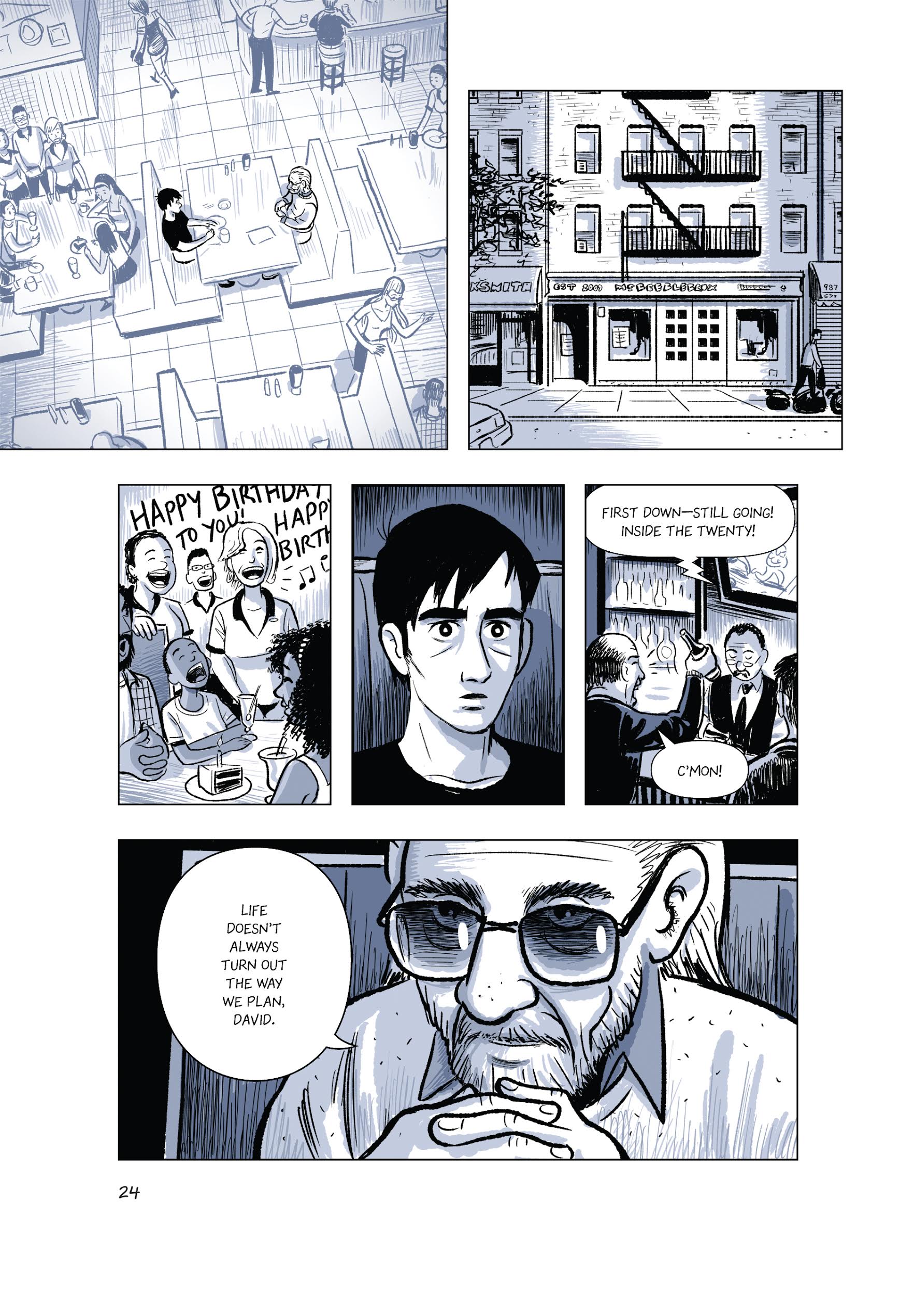

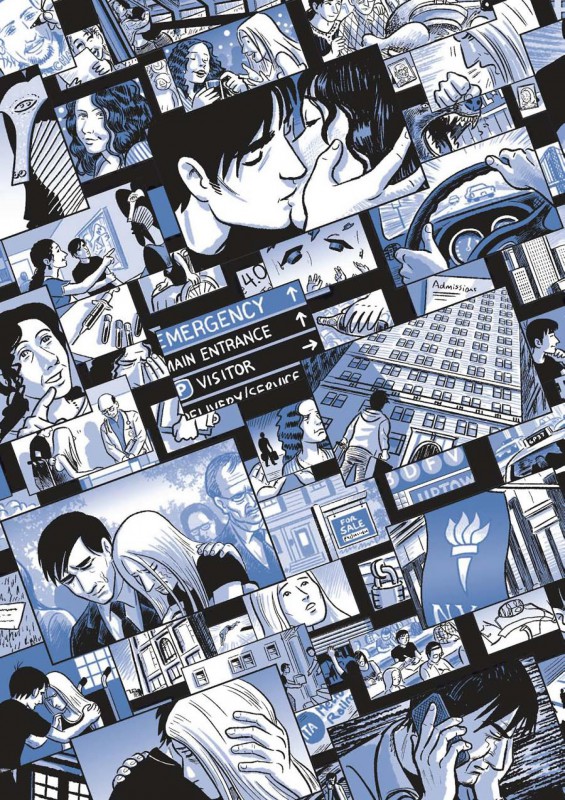

It took much longer for McCloud to complete his most recent work, The Sculptor: his first full-length graphic novel is a five-year, 496-page labor of love that took nearly two full-time jobs’ worth of effort to complete. Indeed, the themes of time and work — particularly how the two are sometimes at odds on the path to creating an artistic legacy — loom large. The titular character, David Smith, makes a deal with death to be able to sculpt anything his imagination can come up with, the caveat being his life is shortened so he has only 200 days left to create.

Given the time and effort he has spent delving into these subjects — based on an idea he’s had for more than half his life — I asked McCloud about his feelings on working as a still-innovating artist in a time of great change, and where time and inspiration intersect.

Nate Patrin

How has social media shaped and developed your perspective on how comics artists share ideas and get support and inspiration?

Scott McCloud

It’s just a much more cohesive scene than it used to be. When I was starting out a long time ago in the ’80s, we had this tremendously slow, laborious process of letter columns where you’d have to wait months for your comic to come out, then you’d have to wait a month for everyone to buy it, then another few weeks for them to actually write the letters; then you’d have to wait for letters to get there so you could pick a couple and run them in the column, which then took a few more months to come out. And that’s how you conducted conversations. Now, our conversations are instantaneous. I think that’s also good — I think anything that helps spur conversations and make them more frictionless, more efficient, more ubiquitous, is all to the good. I think comics, in general, certainly benefit from that conversation — in terms of writers finding artists and vice versa, in terms of good work being passed around (if it’s online, you can simply send out a link). I have seen far more upsides than downsides over the years.

Nate Patrin

Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Patreon have really taken off in the time since you first started working on The Sculptor. How do you see that altering the landscape, especially with regard to artists choosing between getting a publisher and self-publishing?

Scott McCloud

[Crowdfunding] alters the landscape dramatically if it has staying power — and this is the big if. At this point, I think early predictions that these sorts of sites would level things out quickly have proved to be premature. But I think crowdfunding continues to be a vital part of that economy, and to an extent many people, even the optimists, may not have necessarily anticipated. One of the important things you have to remember with crowdfunding is that in traditional, physical markets, when the consumer spends a dollar for something, that dollar is reduced to as little as a dime by the time it reaches the artist. Crowdfunder sites like Patreon and Kickstarter might take a cut, but it’s nowhere near as big a piece of the action as in the old system. Now, you can really see the power of the consumer dollar – and that power is impressive. I’m certainly watching that space. It looks increasingly like it might be a viable option, long-term, but we’ll have to see.

Nate Patrin

Where did you draw inspiration for The Sculptor, specifically with regard to those themes that had some connection to your own life as a working artist?

Scott McCloud

I think, in many ways, those themes are part of the inner narrative for almost any young artist who’s just starting out: there’s this big mysterious world or gateway through which you can pass and be seen by many, many people, and be remembered by many more. You just have to find that gate; then, you have to find the key that unlocks that gate. But, as you get older, you don’t necessarily see things in quite those terms anymore. I conceived of this story as a young man — the basic story itself goes back a few decades, really. I’ve been carrying it around in my back pocket for a very long time. So, it has the flavor of a young man’s story. But I’m also trying to tell it through the eyes of an older man, as best I can.

Nate Patrin

I feel like there’s this balance, trying to find middle ground between being young, when you have a lot of time and energy but not enough experience or skill to be where you want to be creatively, and that place where you’re older…

Scott McCloud

Well, it’s more actually trying to preserve the vitality of that young ambition and those big ideas, while bringing them into focus with the perspective and acceptance that comes with age – the idea that, ultimately, nothing lasts. I want to try and maintain the bold colors of the first while bringing in some of the subtler hues of the latter. I don’t think it has to be either/or. I don’t think it just has to be a blending of the two either. I think you can have your cake and eat it, too, if you do it right.

Nate Patrin

What led you towards the traditional graphic novel format after years of working in webcomics (and with all the possibilities inherent in writing for a specifically online medium that entails)?

Scott McCloud

In a lot of ways, I’m taking the same aesthetic strategy now that I have had before, which is to take the format I’m working in and push it to its limits. When that format was digital, I tried to push digital to its limits and do things that could only be done in digital. And now, I’m pushing in print to do the same thing. I’m trying to find the limits of print and really stretch it as far as I can. When I was making my earlier experiments in digital comics, some people accused me of being anti-print. That wasn’t it at all. I simply thought that if we’re going to make the choice of experimenting in that realm, we should commit to it. We shouldn’t try to have it both ways. We shouldn’t try to create something for the web that would look just as good in print, because that is never going to really work. You have to decide; you have to commit. You have to design for that format. I’m just doing that in print now: I’m designing for the device.

Nate Patrin

What were some artistic techniques and habits you had to either get the hang of or out-and-out change as this process developed? For example, before The Sculptor, you’d been working in a more serial format when it came to fiction.

Scott McCloud

I’m probably best-known for the books that came out as books — my nonfiction books, like Understanding Comics – so, in many ways I think that’s sort of my native format. I worked a little bit in serial comics at the beginning of my career, and then I had a little side road working on some Superman comics and whatnot. But, for me, stand-alone books have been the way to go for a while. This time it was just a bigger, more complex challenge because of the scope of this particular story — and, of course, the fact that it’s fiction.

Nate Patrin

With that scope in mind, and the time and effort you put in this book, were there any moments where you looked at a page, say, two-thirds of the way through, and then referred back to earlier pages to notice something had unexpectedly changed in the way you were doing things?

Scott McCloud

Actually, returning to fiction, I had a lot of readjusting to do. And I got better at it as I went, to the extent that when I finished drawing the last pages of the book, the first 50 pages or so looked kind of shitty to me (laughs). I didn’t much like them anymore. So, I convinced my editor to let me go back and rework them — not just the drawing, but the story. I made many changes in those first 50 pages, because I better understood what the story was about, and I better knew how to execute it. Some of the earliest pages in the finished book are actually among the last pages I drew.

Nate Patrin

What surprised you the most about the working process this time around?

Scott McCloud

I wouldn’t say “surprised,” exactly, but the most gratifying part of the process was that I took the process of revising my layouts more seriously than I ever have before. I did a rough draft of the entire book in quite a lot of detail before I drew a single finished panel, and then I actually revised and revised and revised that rough draft. Five hundred pages of rough layouts, done four times — I did four drafts before I ever drew a single finished panel. And that was really gratifying, because it helped me grapple for the first time with the deeper challenges of crafting a large work of fiction.

Nate Patrin

Is it true that you worked almost non-stop, 11-hour days on The Sculptor?

Scott McCloud

Yeah, 11 hours a day, seven days a week, for five years — except for the last year, where it was more like 13 or so hours per day.

Nate Patrin

What does it take to remain that engaged with a project for a long period of time?

Scott McCloud

It’s easy — I liked the story! (laughs) And I liked the process of working on it. I knew that, when I was done with it, my wife and I would go and play and have fun. It’s just how our life goes: I work very hard on a project, and then we take time off and have fun and travel after that, while we’re promoting and doing lectures and workshops. There’s a kind of dynamic balance there. But I didn’t mind the long hours at all. I looked forward to sitting down at 8 a.m. every day and drawing.

Nate Patrin

How did it feel, upon completion, knowing that an idea you’ve had for more than half your life was finally realized?

Scott McCloud

It felt great, even though it wasn’t a perfect work in my eyes. I mean, it’ll be no surprise to any working artist that I’m very keenly aware of every drawing that doesn’t quite look right — every face that’s a little cockeyed, every figure that seems a little stiff; that’s all I can see when I open this thing. But that said, I know that this is the best book I could make at the time. Knowing that you did the very best work you could under the circumstances — what more can you ask for, really?

Related links, events and information:

Scott McCloud will be in the Twin Cities on Sunday, February 15 at 4 p.m. for a reading and book-signing, co-presented by Rain Taxi Review of Books and Common Good Books, at Macalester College’s John B. Davis Lecture Hall. This event is free and open to the public.

Find more about The Sculptor, McCloud, and his various other projects and publications, online and in print, on www.scottmccloud.com.

Nate Patrin is a lifelong Twin Cities resident currently residing in St. Paul’s Uppertown neighborhood. He has written about arts and culture, particularly music, for over 15 years, and also counts graphic novels, film, and visual design among his many aesthetic interests. His work currently appears in Pitchfork, Wondering Sound, Greenroom Magazine and elsewhere.