What Do You See When You Turn Out the Lights?

Poet, professor and art historian Stephen Tapscott gives a close reading of the bold new photographic work by Tucker Hollingsworth, situating it in the larger context of Modernist "self-consciousness" about creative process, technique and materials.

One characteristic of the ongoing tradition of high Modernist art of the last century-and-a-half has been a rewarding, exploratory self-consciousness about the means, the strategies, even the material processes of the production of the artwork itself. What interests me about the Camera Noise series of photo-images by Twin Cities-based photographer Tuckaghrie (“Tucker”) Hollingsworth is how his lively prints represent a serious attempt to join this late-Modern experiment in material self-consciousness with the ongoing energies of the New. He’s creating a new fusion for the new century, in the field of photography. The surprise, for me, lodges in the sheer physical pleasure of the enterprise: for as cerebral as the implications of these images are in their historical and technical self-consciousness, the resulting prints are also accessible and playful and textured, like textiles. The eye strokes their surfaces widely; visually, their evident intelligence is kind of sexy.

The ambitions of Hollingsworth’s Camera Noise series are, I think, continuous with the explorations of the material self-consciousness of the means-of-production you see in earlier Modernist forms. Hollingsworth’s experiments in digital photography’s technologies of abstraction and randomness and pattern engage those earlier ambitions, in up-to-date terms, and bring them—bring photography—once again into the tradition of American “representational” high art, but with a twist. The “impressions” that Impressionist painters aspired to register, for instance, were the physical “sensations” of the process of looking. The metaphor of the impression/sensation derives (through Monet) from the processes of the printing-press (it “impresses”): as dots and jibbits of light-and-color flecks, the lumina of the visible world, strike the color-receptive rods and cones of the retina, patterns or sensations of vision emerge. A blue dot nestled with a yellow dot generates a sensation of quivering green — pointillism.

The Impressionists’ experiments in the physical sensations of perception opened the way toward later modes of visual abstraction: first, in terms of the way the eye actually observes; then, in the way the formal and material dynamics of representation render what the eye registers; and eventually to the ways the actual means of representation introduce changes during the art-making process of using the materials of the medium (paint, or stone, or bronze, or paper and ink, etc.). You see this self-consciousness arising in different art forms as well: in attentions to the nature of the form and material in design-arts (from Louis Sullivan to Victor Papanek); in the qualities of particular instruments or the nature of silence and repetition in musical forms (as in, say, the opening notes of Strauss’s Don Juan through John Cage); and in choreographers’ attention to the muscles and joints and physical health of the dancer (from Nijinski and Isadora Duncan to Bill T. Jones).

That self-consciousness lies behind an artist’s selection of materials, and also in the consideration of how those materials’ qualities might affect the content and form of the finished work. Consider Rodin’s willingness to let parts of his statues remain stony stone or rough bronze, or Joseph Beuys’s interest in wax and wool, or composers’ use of new objects to make new sounds. In dramatic works, such awareness is evident in the nature of performativity employed: the theatricality of Ionesco and Genet; the documentarianism of Peter Weiss, Anna Deveare Smith, or The Laramie Project. For writers, it lies in the reflexive qualities of words and self-referential literary forms (think of poems about poetry by Wallace Stevens or William Carlos Williams or Marianne Moore). Consider the fact that, for a century now, literary manuscripts are typed or printed-out, not hand-written — rendered by means of the printed “impression” of inked-type-on-paper. (Joyce’s Ulysses concludes Bloom’s narrative—its sequence of self-conscious historical styles– with the world shrunken to a huge dot, a full-stop black-hole of punctuation to mark “the end of the novel.”) Over a long time, the material of the medium became the message.1

In the Camera Noise series, Hollingsworth’s bouncy, cerebral images bring these long-familiar energies of formal self-consciousness into an emergent art form working in and with digital technologies.

It’s no wonder Hollingsworth’s prints look like textiles: in a real sense, in making visible all the typically disregarded “supplemental” visual information around us, he’s showing us the veil through which we see, and through which the world comes to us.

Hollingsworth begins with the basic reality of the digital imaging process in which units of light are captured by a camera sensor, sorted (by several filters of de-mosaicizing algorithms or by silicon-based receptors), transformed into electrical or electromagnetic impulses, and filed as data. Unlike traditional film — which “caught” the light in chemicals spread on a receptive plane — digital technology renders the light-forms of our vision of things as bits, or units of electrical impulse, and then changes them into data. A digital camera catches light in pieces through a lens, distinguishes them by wavelength, transmutes the visual data into electrical signals, sorts them in pixels, and stores them as bits of information with discrete mathematical values, then keeps them available as a code be read by a program for a screen or a printer. This transmission — units of sight becoming snippets of photo-electrical energy becoming pieces of informational data — is the material basis of the new photographic process.

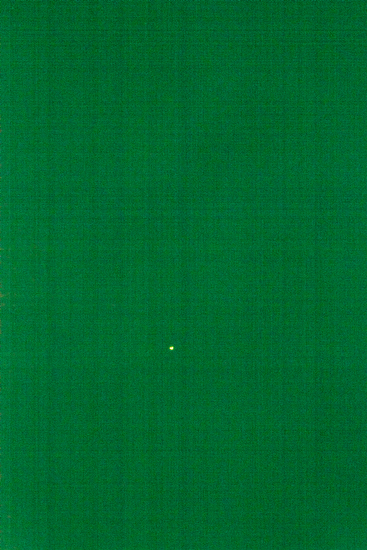

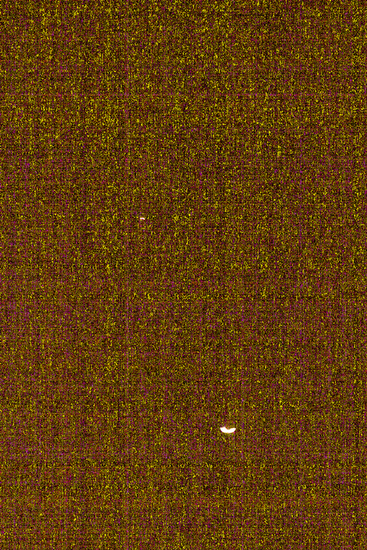

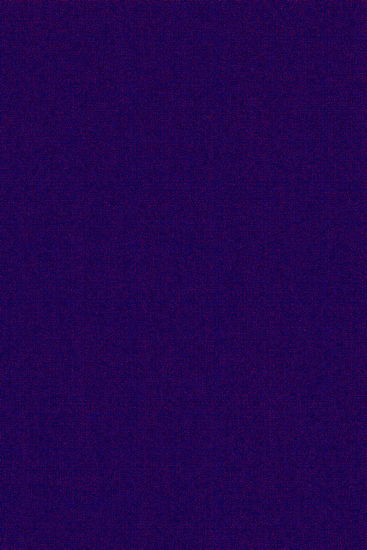

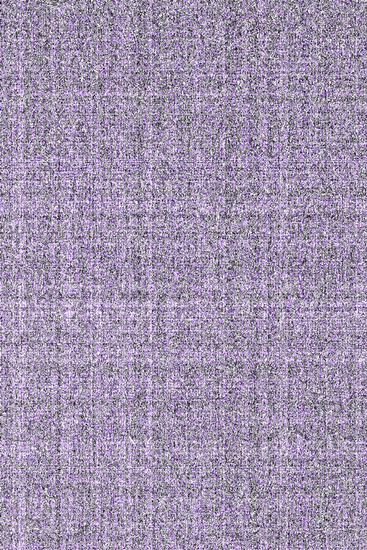

Here’s where Hollingsworth gets interested—and interesting. Lots of conditions, external and internal, can and do interrupt and influence the process of digital imaging. And they leave traces: of things that are more-or-less-randomly there, of the process of transmission, or of the technology itself. The digital mechanisms of seeing and transforming and sorting in this way can be too sensitive for a simple “realistic” representation; the process can capture “too much” information. Random events, like ambient temperatures, can affect how patterns of light and color are registered; the camera sensor might have its own patterns of “seeing,” even when it’s not “looking” to register a form or a pattern, and so on. We’ve all taken digital pictures in which “extra” pixels, not part of the “realistic” content, show up on the screen or in the print. Those random dots, often in blips or fogs or patterns or or plaids or textures unique to the camera or specific to the event of the process, are called “camera noise”: those electrical bleeps the camera itself registers as pertinent data but which are not “part of” the picture we had thought we were shooting. Most of the time, we (amateur) photographers want to eliminate such “extra” information, regardless of the fact that the camera dutifully registered its data as “there” to be seen, stored, and repeated. (In fact, some of the most interesting work in astrophysics these days is finding ways to use these registers of “invisible” energies, by carefully filtering and examining the visual “noise” of space that digital telescopes capture.)

Occasionally the blips or scatterings of “supplemental” information captured in these digital images are indeed random, but they often behave like patterns. Sometimes they are geometrical and related to the shapes the electrical energies or mathematical data assume; sometimes their blending and constituent colors are informative, sometimes not. Sometimes there are suggestions of figuration from the objects in the world that the camera is “seeing,” so that the “camera noise” is in fact related to the photographic work of representation. Sometimes the camera itself, or the technology of the kind of sensor in the camera, produces characteristic patterns—or a lack of pattern—or intermittences. Often such noise is part of what a larger pixelated image overlays or replaces, when we superimpose a larger field of color-activated pixels onto the visual substrate. No wonder the patterns look like textiles in Hollingsworth’s formats: they are in a real sense the veil through which we see, and through which the world comes to us.

Hollingsworth’s images are located right there, inside the camera at the moment – or just before the moment—when the camera is technologically “seeing” for us, sometimes seeing “too much” of what is there, or misinterpreting signals, or imposing its own patterns onto what it tells us is “out there” in the world. Hollingsworth’s Camera Noise prints capture and meditate on what, through the camera, we see without seeing, or what is “supplemental” to our vision. But the supplement is essential to the process. Hollingsworth mediates and meditates on these media patterns, in novel and haunting “mediatations.”

And they are rendered large, in big, elegant, painterly prints: the images value and revere, and sometimes play with, these half-abstract material patterns of color and form and visual rhythm that are part of the ghostly essence of digital photography itself, but which in normal practice we systematically arrange to ignore, to wipe off, or to regularize into realist perceptions. Instead of peeling away the noise to clarify the realist overlay, Hollingsworth peels away the superposed realist image and works with the underlayer, finding hidden form in the basic processes of digital trans-formation. He renders the “noise” into a kind of patterned visual music.

Hollingsworth’s ambitions, as I say, are related to those questions that opened the Modern era and which continue to define many of the artistic ambitions of our current era. Those ambitions revisit Cézanne’s concerns, which he confided to his journals, that maybe his sense of sight was distorting the world as it exists; or Picasso’s prints and sketches, in which he brooded and joked about how the tense desires flowing between the artist and the model might be changing what was present to be drawn; or Heisenberg’s famous dictum, “the very act of observation distorts that which is being observed”; or Wittgenstein’s commitment to finding philosophical truth in the way we talk when we are simply talking with one another, and not deliberately “philosophizing.”

In this sense, Hollingsworth’s important images, in their shifting patterns and delicate coloration, in their thinky sensuous textures, are happily accessible and fun. But they work equally well as an elegant registry of the materiality of the workings of the digital body itself. Some of his prints invoke a place so deeply within our mediated sight as to seem like satellite shots from another galaxy, and yet –new and bold and strange as they look – the images still feel recognizable and pleasurable. In his funky baritone, Ringo Starr once famously asked, “What do you see when you turn out the lights?” And he answered: “I can’t tell you, but I know it’s mine.”

Related links and information: “Tucker Hollingsworth’s Camera Noise: A Primer”: Read Stephen Tapscott’s breezy appendix to this essay on the mnartists.org blog – find definitions of terms, specs and technological context for Hollingsworth’s photo prints.

Tucker Hollingsworth: Inside the Camera/Noise is on view through November 30 at the Chowgirls Parlor, 1224 2nd St. NE, Minneapolis. The exhibition is open by appointment (651-955-6031); there is also a reception Thursday, November 15 from 6 to 10 pm.

Find more information about the artist on his website: www.tuckerhollingsworth.com.

About the author: Stephen Tapscott is s a professor in the humanities at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, teaching, poetry, aesthetics and photography. He is author of eight collections of poems and essays and has a new book coming out soon, about the photographer Eadweard Muybridge and his trial for murder. He is also a translator from Spanish and Polish, most popularly of Pablo Neruda’s Cien sonetos de amor [One Hundred Love Sonnets]. He splits his time between Cambridge, Massachusetts and St-Denis, France.