Reanimating ‘Dance Works’

Camille LeFevre wanders through the Walker's "Dance Works" exhibitions of Merce Cunningham's artist-created props and costumes, musing on the post-performance life of these set pieces, and the power of the 'kinetic imagination'.

REALLY, NOW — IS THERE ANYTHING ORIGINAL LEFT TO SAY about the work of Merce Cunningham? Yes. I discovered a few things while watching a video in which local dance artists talk about Cunningham’s work, which is part of the exhibition Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham/Robert Rauschenberg at the Walker Art Center. The talking heads included Sage Cowles, a long-time board member (and/or director) of the Cunningham Dance Foundation, the co-artistic directors of the former New Dance Ensemble (Linda Shapiro and Leigh Dillard) and a couple of that company’s former dancers (Stephen Rueff and Denise Gustafson).

A not-so-tangential tangent: New Dance Ensemble (NDE), in existence from 1981 to 1994 (although after 1991 it was known as the New Dance Laboratory), was based aesthetically, in part, on Cunningham’s technique and influence. NDE’s years of operation correspond with my own early development as a dance critic: I “cut my teeth,” so to speak, on the ensemble’s work, which was technically rigorous, aesthetically revelatory, and consistently bar-setting as the ensemble’s marvelous dancers performed works by such Cunningham-influenced choreographers as Ralph Lemon, Doug Elkins, and Douglas Dunn. New Dance Ensemble was also, during Dale Schatzlein’s tenure as the Northrop Dance Series curator, the only local dance company chosen to perform on Northrop’s stage as part of a season.

Shapiro, forever an enthusiastic advocate and articulate proponent of Cunningham’s work, mentions at one point during the aforementioned video that, in an essay, Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown notes how everyone talks about how the choreographer collaborated with his décor makers, composers, lighting designers, etc. In fact, she explains, one of the truly revolutionary aspects of Cunningham’s approach to performance (among many) was that he gave other artists the freedom to do their own thing, to manifest their own vision, independent of one another.

In other words, the fact that lighting, décor, costumes, music, and choreography came together for the first time during the premiere — and somehow made sense, evidenced connectivity, generated dramatic moments and emotional resonance, and resulted in a holistic aesthetic presentation — was a testament to Cunningham’s knack for choosing as his “collaborators” the most innovative artists of his time (whether in the 1960s or early naughts).

The Walker’s acquisition of artifacts created or provided by these visual artists — of which, a selection by Robert Rauschenberg and Ernesto Neto are currently on view — provides us with the rare opportunity to study the costumes, sets and artworks in a static condition. Seen in this context, we animate them with memories of past performances, or with our own kinetic imaginations as we pass before them, or under, or through their spaces. Take Neto’s otheranimal. Created for the dance work Views on Stage, the enormous biomorphic form is currently suspended high up in the theater-like fly space of the Perlman Gallery.

Bulbous and grotesque, an exaggeration of male genitalia literally dripping with testosterone-infused intent, the fabric form nonetheless functions as a kind of circus big top that invites contemplation, especially when lit in shades of midnight blue or terracotta. During the Walker’s recent Sound Horizons performance, musicians created sonorous soundscapes of otherworldly tones that reverberated beneath the installation. Such interactions aren’t limited to scheduled performances. Go ahead. Dance underneath the Neto — but take care to avoid its pendulous appendages should you find yourself inspired to leap.

______________________________________________________

Go ahead. Dance underneath the Neto — but take care to avoid its pendulous appendages should you find yourself inspired to leap.

______________________________________________________

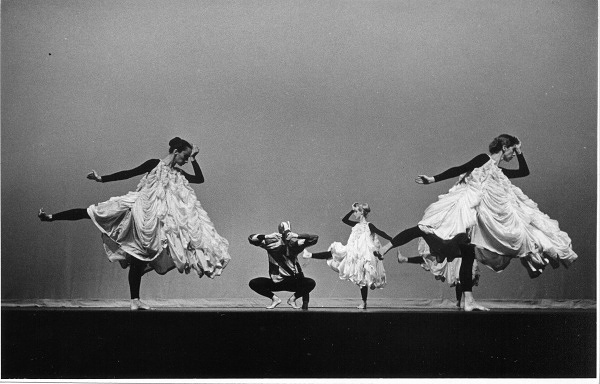

Upstairs, in fact, where Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham / Robert Rauschenberg is installed, you can pick up a card with suggestions on how to move through the gallery in relationship to the work. “The parameters of this gallery are fixed within the walls of the space, but you are not. Consider this idea as you move throughout the room,” reads the card. One suggestion is to walk along Tantric Geography — a row of five chairs alternating with bicycle rims — with or without a friend, while stopping periodically to face one of the chairs. Another is to imagine walking while wearing one of the parachute dresses from Antic Meet. With their gathered tiers of heavy (yet, while descending to earth, apparently gravity-defying fabric), the dresses seem designed to subvert the weightless articulation of the Cunningham dancer’s body and obscure the precision with which they manifest Cunningham’s choreographic intent. How would it be to lunge, tilt, curve, leap, and spin bearing the shape, weight, and swing of those parachute dresses — stopping only to strike the hand-to-forehead pose with which Cunningham poked fun at Martha Graham? Exhilarating and exhausting, no doubt.

Now put down the card and experiment on your own. Pull open every drawer with the worn pointillist-painted tights and leotards from Summerspace and sense the fabric’s scratchy texture and the dancers’ sweat-soaked rigor (along with a giddy time-traveling sense of brushing with celebrity). Laugh at Carolyn Brown en pointe as other performers roller skate around her in the film Pelican. Closely examine the vernacular textures, rips, layers, materials, and colors of Rauschenberg’s combine for Trophy II. Note the rhinestone bracelet from Nocturnes (just like those in vintage stores) and consider whether you really could balance that mirrored headdress.

Meanwhile, here is the original Carolyn Brown quote Shapiro refers to in the video mentioned earlier; it is from James Klosty’s book Merce Cunningham: “The truth is, Merce is no collaborator. He is a loner. He does not work with the lighting designer, set design, costume designer, or composer. And it is here that [John] Cage’s notions of anarchy and of coexistence as practiced by Cunningham work in strange ways.” Brown goes on to describe how “we would hear the music and feel the lighting in the first performance. I will not pretend that this is not extremely difficult for the dancers.” Sudden bright lights or a plunge into darkness, loud noises or a grating score could quickly disorient a dancer — who had to right themselves just as quickly. “But the official Cage-Cunningham dogma requires the autonomy and freedom of each theatrical element — movement, light, sound, and décor,” she continues. And as the dancers contend with the circumstances, chaos, contradictions, and complexities of this methodology, “it’s just possible that these conflicts and tensions, and the dancers’ constant attempts to deal with them contribute to making the experience of Merce’s theater so extraordinary.”

As visitors to Dance Works, which presents such theatrical elements in a static condition, it’s up to us — as the movers in space — to re-animate these artifacts through the kinetic imagination, with the truly independent vision and freedom of a Cunningham collaborator.

______________________________________________________

Related information and links:

Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham / Robert Rauschenberg is on view at the Walker Art Center through September 9. Dance Works II: Merce Cunningham / Ernesto Neto closes soon, on July 8. Dance Works III: Merce Cunningham / Rei Kawakubo will open this fall, on view from October 4, 2012 through March 24, 2013.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is an arts journalist, teaches arts journalism at the University of Minnesota, and the author of The Dance Bible: The complete guide for aspiring dancers.