Too Much is Enough

Critic and curator Corinna Kirsch muses on Andrea Stanislav's new exhibition at the Burnet Gallery in Chambers Hotel - at once "seductive and repulsive" in its campy glam, filled with tricky plays on word, meaning, and post-'60s pop culture touchstones.

To read is to find meanings and to find meanings is to name them…I name, I unname, I rename: So the text passes.

Roland Barthes, from S/Z

For Andrea Stanislav, too much is enough. Her exhibition titles alone point to states of extremity, even impossibility — Lightning Struck Itself and River to Infinity, the latter belonging to her 2008 solo exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. In the artist’s current solo exhibition at the Burnet Art Gallery in Chambers Hotel, Lightning Struck Itself (her second in this space), the impossible, in particular, manifests itself in her work through the impotence of visual and text-based communication. Simply trying to see the images or read the text embedded in her glittery, bright, and shiny surfaces is like wrestling with an enigma, as her images fade and flicker under the gallery’s light.

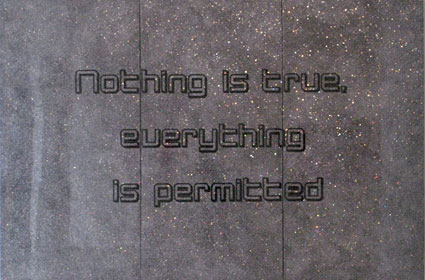

The works in this exhibition resist a clear orientation with either sculpture or painting; instead, almost all the pieces are constructed through a multi-step process, involving an image or text printed onto a two-dimensional surface, which is then covered with pink or gray glitter; finally the contents are sealed in with a clear polymer veneer. Equally seductive and repulsive in their campiness, Stanislav’s works consist of so many pop culture references; taken together, the cryptic bits of text are like a crib sheet for a course on post-1960s rock music and film — see Pressure Drop (2009); Bohemian Atmosphere (Performance) (2009); and Change Will Do You Good (Gang of Four) (2009).

Are these merely insiders’ jokes, feigned hipness, or an attempt to capture something of the late-20th century’s zeitgeist? Whatever their individual denotations, Stanislav’s appropriations also double as inauthentic markers of a past era, suitably trapped under an airless, plastic veneer.

Her works point to the trickiness of language and how, cluttered with secrets and codes, words always mean more than one thing. Stanislav’s triptych Nothing is True, Everything is Permitted (2010) consists of the work’s title running across the surface billboard-style. The origin of the title phrase, a cliché heard innumerable times in a variety of contexts, has been obscured through its continual cultural reuse. It’s apt then that, in this work, the dark colored text emerges from the dark gray, glittered background only when the light hits it at certain angles; even then, the text remains largely submerged. Nothing is True allows marginal access to a reading of its text, and only then, at certain viewpoints. And preventing a viewer from beholding its surface in its entirety can be nothing other than aggressive.

The lack of clear legibility, in both the physical image of the text and the origins of the phrase, evokes simultaneous experiences of remembering and forgetting. This slippage is exemplary of one aspect of what Barthes has described as the inherent plurality of text — that is, the irreducibility of any language to a single meaning or truth. The near infinite possible readings of any text, combined with the endless stream of associations that any single reader can bring to it, means that some interpretations will inevitably be forgotten, or at the very least, remain submerged until a capricious event recalls those memories, those interpretations, from a previously lost past.

Understood that way, language takes on an immeasurable immensity much like, say, the concept of a River to Infinity. However, this torrent of possible associations quickly regresses to a never-ending absurdity. Stanislav’s vertically oriented works, her “Zagadkas,” Zagadka (the riddle), Zagadka (pink), Zagadka III, while lacking any textual references on their surfaces, recall the monoliths that populate 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Barnett Newmann’s “zips.” Again, language is slippery and filled with ciphers, haunted both by ghosts of art history and of culture’s past. As inclusive as art has become, allowing any range of topoi, it has also become more hermetic, a closed system of endless associations. Stanislav’s texts, sealed underneath hardened plastic and trapped in a landscape of undulating glitter, confronts this inescapable conundrum of language. The plurality of meanings, and our inability to control them all, leaves us empty. In the end, we are alone, even while surrounded with all the words in the world.

Related exhibition details: Andrea Stanislav – Lightning Struck Itself will be on view at the Burnet Gallery (Chambers Hotel) through March 7. There is an artist talk with Stanislav scheduled for February 22, 6 – 9 pm at the gallery.

About the author: Corinna Kirsch is a curator and writer currently living in Minneapolis. She received her MA in Modern Art History, Theory, and Criticism from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Motherwell Journal, …might be good, Proximity Magazine, and her forthcoming writing will appear in ART PAPERS.