Trauma is a Time Machine: Art and Healing in Troubled Times

Recent exhibitions at Public Functionary and Macalester College's Law Warschaw Gallery address two sides of a question that haunts this place: how to shed the awful weight of trauma and rekindle a utopian imagination.

“Unimagine this.”1

Trauma tears the mind asunder: what cannot be borne must be buried. Lightning fast, trauma severs the self or slowly erodes its very foundations. An involuntary response, trauma exiles the incomprehensible far from the reach of reason. Willpower pales in comparison to the forces unleashed by trauma: to protect an organism’s survival, the wholeness of self splinters. What remains is a fragmented consciousness, a split self haunted by a past that refuses to be over. Trauma is a time machine: broken, it only ever goes one way.

Nobody chooses trauma. Whether it strikes individuals or communities, trauma compromises the integrity of a whole: a deep sense of self withers, but survives in a hibernation-like state. In the absence of what once was, archetypal dreams and fantasies may rise to fill the emptiness.2 For communities afflicted by such disaster, tradition itself withdraws. Thus dispossessed, the traumatized are vulnerable to the rise of counterfeit tradition, “one characterized by reduction to the exoteric and lack of subtlety.”3 The ossified half-life of the counterfeit takes the place of the rich textures and fabric of living, breathing culture. Attitudes instilled by faux tradition are contagious. And so trauma travels. It can span generations, its traces visible in brains, bodies, genes.

Yet trauma, says Resmaa Menakem, is not destiny. Though trauma may be part of our inheritance, tools for healing are at hand. Menakem’s book, My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (2017), seeks to offer precisely such tools, specifically for healing from racialized trauma. Firmly ensconced in the self-help genre, Menakem’s manual is timely, accessible, and compassionate. The book and the exhibition at Public Functionary occasioned by its release, a group show titled Reckoning, are part of a recent attentiveness to the places where art and trauma touch. Though sensibilities and modes of engagement vary, art and trauma seem to be having a moment. This moment started to coalesce in the public discussions of Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012) that led to the sculpture’s removal. Rather than pathologize, belittle, or ridicule trauma, the conversations between Dakota elders, representatives of the institutions, and the artist, recognized the relevance of time unbound from linear progression.4

Trauma collapses past and present. It suspends the passage of time. Not only does trauma alter the experience of the past: it steals the capacity to imagine a future. Since the logic of trauma asserts that the worst already has happened, life seems over; impossible to plan, dream, and believe in wild possibilities, in change. The literature on trauma calls this “a foreshortened sense of the future.” To tempt the mind into unruly speculation, Iyapo Repository, a project in residence at Macalester College’s Law Warschaw Gallery in St. Paul, asks for participation in creating an archive of the future. Envisioned by two New York-based artists, Ayodamola Okunseinde and Salome Asega, Iyapo Repository pays homage to Afrofuturism’s Octavia Butler and the heroine of her Xenogenesis trilogy, Lilith Iyapo, but charts its own path into a complex not-yet: an archive of what might come to be that holds the imaginary residue of an even more distant future.

Trauma collapses past and present. It suspends the passage of time. Not only does trauma alter the experience of the past: it steals the capacity to imagine a future.

Both Reckoning and Iyapo Repository share an implicit interest in healing, though what that means in each case differs. In general, healing from trauma requires integrating, piece by piece, what once was divined beyond the pale of the bearable. Healing means waking up hungry ghosts and putting an end to their hibernation. The path to such reunion is haunted. Early students of the human psyche in the European tradition—Freud, Janet, Ferenzci, Jung—observed the strange obstacles their patients faced. They witnessed a curious reversal: the terrible guardians installed to ensure that never again the self would be violated turn on the emerging exiles. A once protective force morphs into a prison warden, a relentless gatekeeper unwilling to entertain the possibility that the danger might be over, that the pain might be borne. Healing from trauma means appeasing two kinds of demons.

The individual process resembles recovery from collective trauma. For Lebanese artist and author Jalal Toufic,5 the process involves resurrecting tradition, unmasking counterfeit traditions and remembering what the surpassing disaster withdrew from those in its thrall: “Resurrection takes (and gives) time.” The sense of futurity cannot be coaxed from the recesses of ruptured memories in a rush. Neither can the necessary mending happen in the mind alone: the body harbors trauma. In the words of trauma expert Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score. The title of his most recent book firmly places the body at the heart of healing.

For Van Der Kolk, the public hearings for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in post-Apartheid South Africa in 1996 serve as the epitome of communal healing. His description of traveling with Desmond Tutu is worth quoting at length:

“These events were framed by collective singing and dancing. Witnesses recounted unspeakable atrocities that had been inflicted on them and their families. When they became overwhelmed, Tutu would interrupt their testimony and lead the entire audience in prayer, song, and dance until the witnesses could contain their sobbing and halt their physical collapse. This enabled participants to pendulate in and out of reliving their horror and eventually find words to describe what had happened to them. I fully credit Tutu and the other members of the commission with averting what might have been an orgy of revenge, as is so common when the victims are finally set free.”6

In the deeply resonant communal movement, held by the combination rhythm and sound, suffering was seen, felt, and witnessed. Naming and narrating what happened makes possible a recovery of the belief in agency, a reclaiming of the capacity to imagine a future. This process cannot happen in isolation: it is fundamentally relational.7

Such communal and somatic healing practices lie at the heart of Reckoning. Menakem, a trauma therapist, invited artists to contribute new or repurposed work in an exhibition bookended by the launch on opening night and a listening session at the exhibition’s close. Some of the work illustrates key concepts from the book; other artists engage with trauma head on. Ashley Fairbanks‘ pithy phrases stenciled on the sidewalk and the stairs leading up to the loading dock that serves as the entrance remind us of whose land we are standing on: “This place already had a name.” “This is prairie.” “500 generations before colonization only 20 after.” “Invasive species.” Thus situated, Reckoning unfolds.

The first image to greet viewers combines the face of Hollywood’s Frankenstein’s monster with an Afro and a single feather. Colorful graffiti squiggles and stylized phrases from the book, surround the creature, stitched together from hubris, fear, and fantasy. The white man’s Indian,8 alternately savage or savant, meets Baldwin’s Negro meets Mary Shelley’s creation. Dubbed “Frankiebaby,” the iconic figure reappears on “the merch:” hoodies and T-shirts, the works. “I am trying to be more hip-hop,” Menakem says, when asked about the branded paraphernalia. The mixing of entrepreneurial spirit and trauma recovery is odd, perhaps especially after this spring’s spirited public discussions about who should and should not profit off Black pain in the wake of Dana Schutz’s now-notorious Open Casket (2016) painting at the Whitney. Perhaps it is naïve to ask, along with Seph Rodney, what an art production system would look like, “uncoupled from the need to buy and sell and from the urgency to satisfy one’s ego, and a robust and genuinely respectful civic arena for public conversation, where we prioritize actually seeing and recognizing each other?”9 Art, like counseling, may be many things but is a business, too.

The strongest work in Reckoning grapples with the tensions and futilities inherent in representing pain. Shiraz Mukarram‘s video, Rantings of a well-behaved child (2016), alternates image and voice: a pair of brown feet on grassy ground face us, skin shining wet and smudged with dirt, toenails covered in chipped blue varnish. Meet Jamez, “labeled trans, labeled Black, labeled Jamez.” As soon as he begins to speak, the screen goes dark. The moving portrait questions, what we can know of each other? How much we do see of each other, each other’s pain? “I don’t want to think about these painful things alone.” What can be represented?

In Sayge Carroll‘s Strange Fruit Reunion (2016), small wire trees offer a different kind of re-counting and holding accountable: thin strips of paper memorialize the names of individuals killed by police since 2015. “An incomplete list,” the artist tells me. Her sculptures conjure other trees: Jeremiah Ellison‘s drawing of what Menakem calls the trauma tree, its roots reaching back many generations. There is no beginning or end to its gnarly presence on the gallery walls.

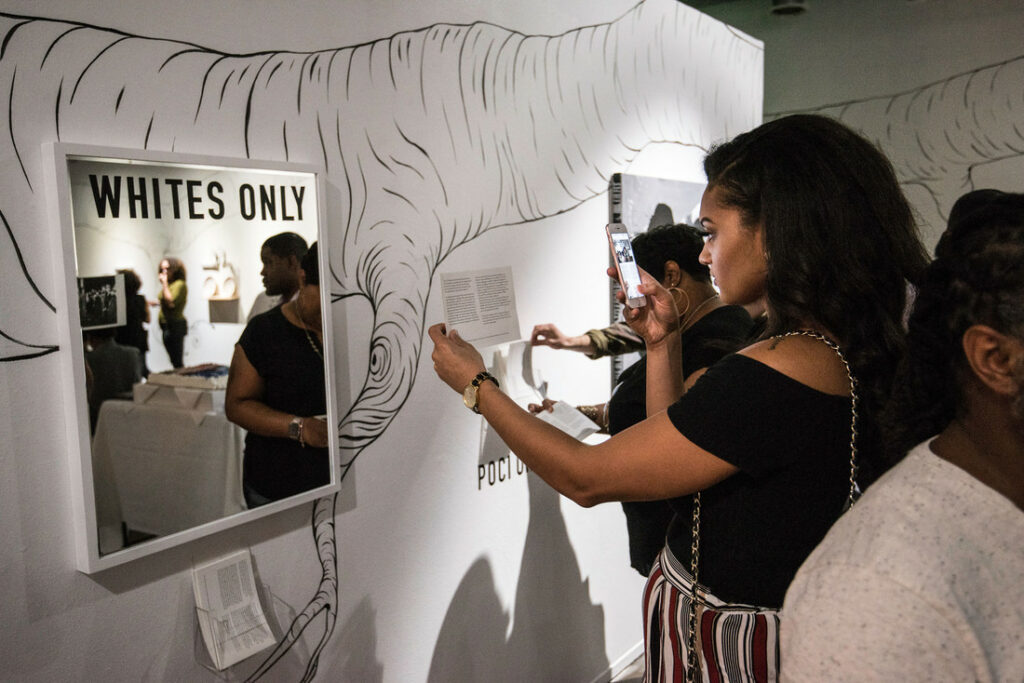

But while trauma may be passed on to us, the work of healing begins in the individual. A collaboration between Mike Bishop, Michael Cina, and Menakem stages one of the book’s experiential exercises in the gallery. Separate sets of instructions ask POCI and white visitors/readers to look at a photograph of a lynch mob taken in Duluth, MN, in 1920. The tree amid a crowd of white faces remains but the three victims’ bodies have been removed in a gesture familiar from Ken Gonzales Day‘s notable exhibition Shadowlands.10 The instructions ask, “What is your body experiencing right now? Do you want to dis-identify with these white bodies? Notice what your body is experiencing.” The exercise is powerful and important. Like Menakem’s work with the Minneapolis Police Department, learning to notice pre-conscious conditioning in the body may be the first step toward a change in policing, an end to officers’ irrational perception of Black male bodies as threats.

My Grandmother’s Hands carries on the distinction between bodies who bear the “soul wounds” of the transatlantic slave trade and bodies who have inherited “white-body supremacy.” The focus on bodies effectively shifts the conversation from questions of individual culpability to a systemic understanding of the depth of trans-generational trauma. To account for the endless capacity for violence, Menakem traces the brutality and numbness required to torture and abuse other bodies back centuries into the European Middle Ages. His reading of history does not absolve the heirs to such dissociation of their responsibility to unlearn reactions falsely assumed instinctive.

Though for the most part the work in Reckoning foregrounds trauma experienced by Black bodies, Menakem aims for inclusivity: “My pain is not greater than anyone else’s pain,” he says (and writes) more than once. No doubt, there is emotional value in such a gesture, given the psychology of suffering Susan Sontag witnessed in Sarajevo in 1994: “To set their suffering alongside the suffering of another people was to compare them (which hell was worse?), demoting Sarajevo’s martyrdom to a mere instance. … It is intolerable to have one’s own suffering twinned with anybody else’s.”11 But while suffering and trauma may not be unique, “not greater” risks a leveling of painful experiences that in turn may erode the awful specificity of trauma. My Grandmother’s Hands thus participates in broadening the scope of what constitutes trauma: any unresolved stress response that lingers in the body counts.

Since I’m not a therapist, I’d rather not get into debates about what should and should not be considered trauma and why. I am all in favor of people having access to the tools to learn how to regulate their system—to pendulate, titrate, learn how to smuggle small fractions of old, exiled pain across the threshold of the bearable. Those are fantastic life skills for anyone. But I am wary about the ever-widening web of victimhood. Let me elaborate. A couple of years ago, a conversation in the hallway of an art school, after class. A student, white, male, earnest and ethically engaged in political activism, tells me, “You have to be a victim to speak with any authority and authenticity. So I started thinking about how I was victimized to make work.” Pain here acts as the badge of something irrefutable. What else does it do?

Consider collective trauma. In Austria, where I spent the first two-and-a-half decades of my life, I witnessed firsthand the destructive, distorting appeal of “the victim myth”: 12 rather than face its complicity in the crimes of the Third Reich, official Austrian post-war historiography cast Austria in the role of Hitler’s first victim. The Anschluss, despite the embarrassing photographic evidence of people cheering the German tanks’ arrival in the streets, was presented as an act of aggression, not the homecoming into the Reich it was marketed as at the time. Until the 1990s, the myth served several purposes: it exempted Austria from paying reparations and acted as insulation for any honest engagement with the crimes of the past. It served as a kind of counterfeit tradition that stuck the culture and people in place, caught in a loop of denial and avoidance. My concern, then: the perverse attraction to the role of victim for the reprieve from accountability it seems to offer. (I say “seems” because, sadly, cruelly, unfairly, the victim is left with the work of healing, work that is challenging, painful, and very eventually rewarding.) Theoretically, we may grasp that most of us are victims, accomplices, perpetrators, and beneficiaries of systemic injustices at the same time, though in different ways; in practice, the position of the victim tends to overshadow all else. Recent electoral politics are a case in point: the self-righteous rage of those who perceive themselves victimized, forgotten, knows no rival.

If anything, the role of victimization as political currency heightens the importance of Menakem’s work. His book offers a didactic toolbox that puts personal embodied practice at the heart of healing from racialized trauma. A similar recognition of individual and communal agency occurred at the panel discussion for Iyapo Repository, when project assistant Mariama Jalloh suggested a shift from dwelling exclusively on “What has been done to us?” to “What have we been doing?” Far from denying the impact and legacy of trauma, the shift is one of emphasis: a reclamation of agency, resilience, and an unruly imagination.

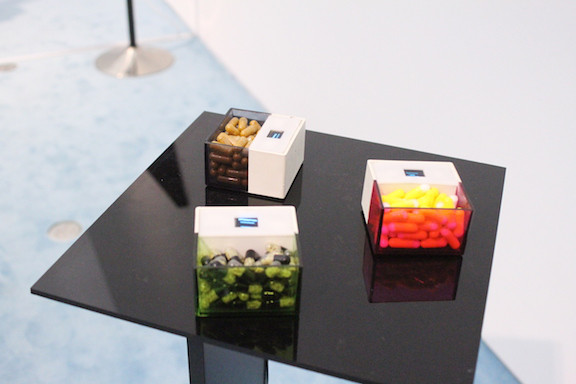

A participatory project, Iyapo Repository collects ideas, turns them into digital prototypes and, occasionally, into physical artifacts dedicated to, as lead conservators Salome Asega and Ayodamola Okunseinde put it, “affirm and project the future of people of African descent.” Some of the artifacts designed and produced for the Repository reference trauma directly, such as the marvelous blue sensory suit “that simulates the feeling of being underwater. This suit has sensory units on the inside that collect data from subject, such as heart pressure, vital signs etc. to evaluate the subject during their ‘underwater experience.’ This suit is useful for helping trauma victims and/or people with water-related phobia as a form of therapy.”13 Imagined in one of the workshops, the suit now exists as a physical artifact, on view in the gallery. A video, part of the Repository’s moving image collection, shows the suit in use, an alien-reptilian costume of otherworldly beauty. And that is precisely the point: to imagine another world.

Though described as an “archival and pedagogical intervention,” the design thinking Iyapo Repository promotes steers clear of didactic instruction. Workshop facilitators provide participants with prompts designed to articulate a general direction. For instance, what kind of a future is this artifact for? Dystopian, utopian, apocalyptic, or revolutionary? Which cultural arena would the artifact be part of? Music, politics, fashion, space travel, security, education, or health? (Perhaps needless to add, this is not a complete list.) A third tag asks for more detailed description of the object: has a motor, transmits data, is wearable, makes sound, changes color, or serves for self-defense. The results never fail to surprise: bio-suits to aid adaptation to alien species, space traveling rockets that emit perfectly pitched sound, or Afromation pills that deliver information directly to the brain.

The goal is not to restrict the imagination to what is possible, but to reach for wild potentialities: “Unlike a possibility, a thing that might happen, a potentiality is a certain mode of nonbeing that is eminent, a thing that is present but not actually existing in the present tense.”14 The goal is fabulation, not as a denial of truth but, as Erin Manning writes, of “history fabulated in the retelling, invented in the interstices of what cannot yet be spoken.” Iyapo Repository shares this approach, which doubles as an attitude, with Idle No More, whose “focus was on education, forward-thinking, not bloodlines.” Addressing trauma directly, Manning goes on, “There is no repayment that can absolutely undo the effects of environmental degradation, no repayment that can still the history of human suffering in the disenfranchised communities of the Canadian North. There is no way to bring back the families destroyed by residential schools. But there are ways of being rhythmically, differentially in-act, of idling no more and asking, collectively, what else? What else can be imagined? What else can we walk toward, or around, or behind? There is a way to claim stories, and to continue to write them.”15

Iyapo Repository‘s storied artifacts work in a similar way: they gesture toward a not-yet and allude (etymologically, play toward) Ernst Bloch’s hope for the “anticipatory illumination” of art. Set free from the imperative of the functional, “which does not let us see anything in it except the use capitalism has mapped out for it in advance,”16 the impractical pleasures of fashion, music, and art may act as instigators of imaginative leaps. Rather than set the record straight, Iyapo Repository radically re-imagines what counts as a record. In Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s words, “To forget debt is to invent a new kind of justice…to seek justice through restoration is to return to the balance sheet and the balance sheet never balances. There is no refuge in restoration. Conservation is always new. It comes from the place we stopped while we were on the run. It’s made from the people who took us in” (emphasis added).17

The place to stop while being on the run is also the place to start imagining what else might be: a national reckoning? A settling with old ghosts?18 A new country, liberated from the annihilation machine unleashed by defenses designed to keep white guilt at bay? By strange convergence, Reckoning and Iyapo Repository address two sides of a question that haunts this place: how to shed the awful weight of trauma and rekindle a utopian imagination. There is no shortage of models and proposals for such repair, attempts at resurrection. But as long as counterfeit traditions and seductive victim myths absolve us of personal and communal accountability, repair and resurrection will stall. Still, there are glimpses of wild possibility: In December of 2016, U.S. veterans got down on bended knee and asked forgiveness of Lakota elders at Standing Rock.19 What does your body experience watching their plea in online videos? For white readers, what would it feel like to identify with these kneeling bodies, their courage to embrace vulnerability? “Notice what your body is experiencing.” This may be the very place where healing starts.

This article was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Jordan Rosenow.