To Say the Truth: Here It Is

Lightsey Darst reviews the extraordinary here it is / here it is by Melissa Birch at the Bryant-Lake Bowl. Remaining dates are September 16, 23.

It’s been ten years since cabaret master Melissa Birch’s last show here in town. Although I haven’t seen her work before, I can imagine that ten-year hiatus has something to do with the highly-worked quality of “here it is / here it is,” her hour-long impossible-to-categorize romp/meditation on womanhood in modern America. A few years might have gone into this creation: no detail’s overlooked. When Kate Lynch squirts ketchup and mustard into a diaper, the ketchup and mustard aren’t simply snitched from BLB tables; no, they’re packed into honey-bears, thus upping the missing-child creepiness of the act.

Birch works her material so carefully that at times the live feel is lost, or the liveness of particular moments— Tamara Ober’’s rangy improv dance, Lynch and Birch’s singing— comes as a surprise. But if there’s something bookish about “here it is,” Birch gets the good side of that too. “here it is” is firmly idea- and text-driven, with a core of sincere intention; Birch gives you plenty of ideas, plenty of lines to hang on to, and she makes you feel included, makes you feel that the whole experience is as intimately yours as if you were reading it in your own room. In fact, “here it is” is as close as the stage gets to the intimate, multi-leveled, nuanced, detail-oriented object that is a modern book of poetry.

The multiple levels in “here it is” are the themes and characters that recur and vary, but also the different modes and techniques Birch has at her disposal. Without being splashy about it, Birch weaves together funny and scary, music and dance, recorded voices and props, entrances and exits. Birch herself can be a flag-waving fear-monger one moment and a bimbo caricature the next (“I know it sounds like I’’ve been smoking crack, but it’s actually Dexatrim”). In Kate Lynch she’’s found a performer as versatile as herself, capable of singing, acting, and dancing (Ober is largely a dancer, though a superlative one), and Lynch and Birch alternate in commanding the stage. Given all the variety of stage action, there are remarkably few awkward bumps in transition: “here it is” delivers a smooth ride, uniformly entertaining.

What we’re riding through, though, is anything but smooth. “here it is” revolves around a key question: What is the power of women? It seems that we should have answered this already, but time has only suggested options, many of which appear on stage. Mother power? See Lynch’s spooky mother-figure, with her idea on survival. Enlightened girly consumerism? Birch’s “Audrey” character skewers this (“I’m taking back my power,” she drawls as she flips her fake hair). A new kind of politics? “I do think women could make politics irrelevant,” declares a recorded voice, in what seems at this point like foolish idealism. Riot girl force? “here it is” comes closest to endorsing this option, with a rousing, stomping finish.

But the woman question is crossed with another vector that gives the first urgency: a 9/11, war-toned, our-times-are-dire theme. “I could die tomorrow confused,” one character says. Perhaps we need the power of women, whatever that might be, to get us out of our current plight.

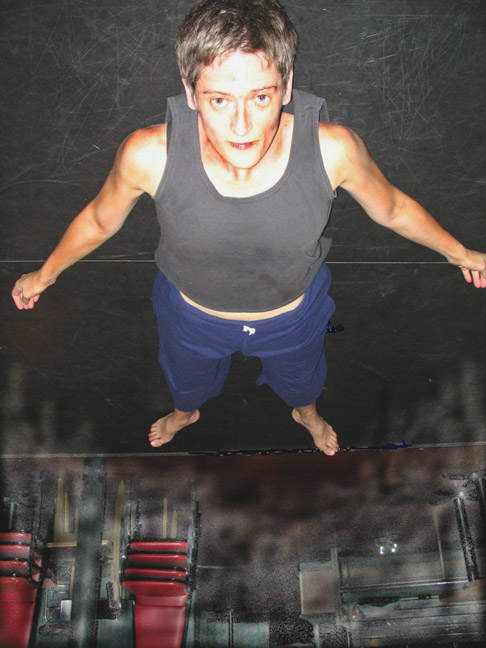

Birch isn’t entirely successful in bringing in this cross-theme. I felt my own reluctance to go back to Abu Ghraib, to 9/11, to jumpers from the World Trade Center. But this theme’s clearly crucial to Birch. She’s got something in particular to say, and it has to do with falling, with balancing ourselves in the freefall of our existence.

It’s better than that—but a few minutes from the end of “here it is,” one feels Birch pushing her thesis. The thesis is a writerly construct, cropping up in essays, books, plays—it’s that moment when you give your reader/audience the kernel, the take-away. Birch provides plenty of take-away, which is nice. But the thesis feels weak. It’s less that Birch’s idea is weak than that the idea of a thesis itself is weak—an old-fashioned kind of truth at odds with the multivalent experience of “here it is / here it is”.

The urge to find and impart truth is itself moving, though. Perhaps Birch could relocate that truth in the “live” moments of “here it is”—the two breaks when either Birch or Lynch sings and Ober dances. To say the truth—well, it’s impossible. But it’s a brave failing to try.