THEATER: The Patriot: Inside “Jasper Johns”

Skewed Visions' latest show, "Jasper Johns," aims to unpack, via a variety of theatrical forms, the eponymous artist's insights into national identity. Lightsey Darst saw the show this weekend, and she offers up her take on their efforts here.

SKEWED VISIONS JASPER JOHNS IS NOT, AS YOU MIGHT THINK, about Jasper Johns; its not biography. Instead, Jasper Johns is a three-part exploration, in three different genres (dramatic theater, film, and movement theater) of themes Skewed Visions three Co-Artistic Directors (Gülgün Kayim, Sean Kelley-Pegg, and Charles Campbell) find in specific Johns works.

Kayims “Flag,” taking on Johnss Flag series, features three immigrants preparing for their naturalization exam. Before the show begins, a truly atrocious naturalization tape plays in the background, in which a heartily cheerful man warns us against being drunk much of the time if wed like to apply to be citizens; and then, in the endless loop of the tape, that same man booms out, Welcome to the U. S.! Voice collage continues into the performance itself: as the three immigrants battle for chairs in the waiting room, one speaker asks and answers naturalization questions (the voice is Kayims, as she prepares for her own real-life naturalization exam); another voice questions why one must be a citizen, why one must pledge allegiance; and still another voice relays her discoveries of various American atrocitiesso different from the stories about America she was taught as a child. Meanwhile, the three immigrants on stage become increasingly violent, stabbing each other with flags, chasing each other with folding chairs, and building chair towers from which to declaim like politicians.

This could easily degenerate into predictable U.S.-bashing, but it doesntpartly because, despite their antics, the three immigrants remain in awe of the doorway they will pass through to begin their citizenship exam. What Kayim’s vignette suggests, instead, is the strange invulnerability of citizenship: one must have a country, and nothing that is done in the name of that country changes that. All nations have their share of absurdities and atrocities; still, we must belong. But she also suggests that we never do quite belong; we never attain that exalted state of citizenship, whatever it may be. I never saw this in Johnss Flag series before, but now I do. Whatever he does to the flagwhether he turns it grayscale or makes it into a visual trick, an afterimagestill it remains the same incommunicative flag, and he remains fascinated with it.

Kayim is aided in Flag by four enthusiastic performers (Kym Longhi is particularly intense). Overall, even though the piece feels structurally weak, as if it could use more shape, the ideas and performances are strong enough to carry Flag through. Kelley-Peggs Watchman/Decoy, based on Johnss target paintings, is not on the same order of conception as the other two pieces, but it does make for an entertaining break between two pretty heavy works.

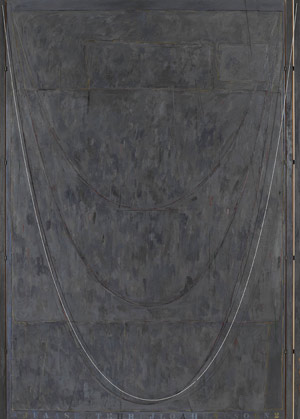

In the final act, Gray, Campbell peers into the surface of Johnss Near the Lagoon, a layered and obscured work. Appropriately, Near the Lagoon, itself, is sunk deep in Campbells work. One clear allusion, a rope parabola that drops suddenly and unnervingly into being (like the string across Near the Lagoon), is all Campbell allows. Otherwise, he delves into Johns’s method and its inherent madness. People in outsize butcher-paper suits (Rosenquists snappy suit meets Beuyss atrocious tailor) rustle-walk across the stage, sometimes popping up into little flat-footed jumps or pausing to howl at their own extended toes. They seem to live in their own formal systemnot real people at all, just people-like beings. Occasionally one wanders over to read a little chunk of text as headachingly distorted words slide across the back wall. Through some marvelous sound manipulations by Elliot Durko Lynch, minor (but creepy) distortions with the first reader slowly amplify into full-scale yowling unintelligibility with the last reader.

Defamiliarization is Campbells game, and its an unsettling journey. And, frankly, it’s an overlong one, too. Campbell loses some intensity by stretching the piece out too far. What he manages to bring out, though, is the troubling impossibility of abstraction. Because, as humans, we depend on social systems, we constantly try to extract social meaning from abstractions, even when it defies us to do so. In this way, were locked in a vase-faces sort of illusion: the images keep flip-flopping from one to another, from meaningful to meaningless. When the paper-suited strangers raise their stiff coats above their heads, they become hideous apparitions, headless and hollow. But wait: they were never people to begin with. We clutch at our interpretive signs, even when these are proven false. Campbell also points out how this fight for meaning intensifies our reaction to abstraction. I found myself hovering between hysterical laughter and terror in the last section of Gray, each made worse by my knowledge that I was creating my own reaction. Abstraction tantalizes, haunts, disturbs.

Ecphrastic (that is, based on or inspired by an image) is a word generally reserved for poetry, but Skewed Visions shows that ecphrastic theater offers a promising direction as well. Skewed Visions uses Johnss work to fire their own stage images, resulting in a piece that stands on its own, while at the same time casting light back on its inspiration.

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.orgs What Light: This Weeks Poem publication project.