The Urban Sketcher

Nate Patrin's sprawling conversation with alt comics veteran, Ken Avidor, ranges from '70s underground comix boom to Robert Moses to the confluence of Twin Cities comics and bike cultures

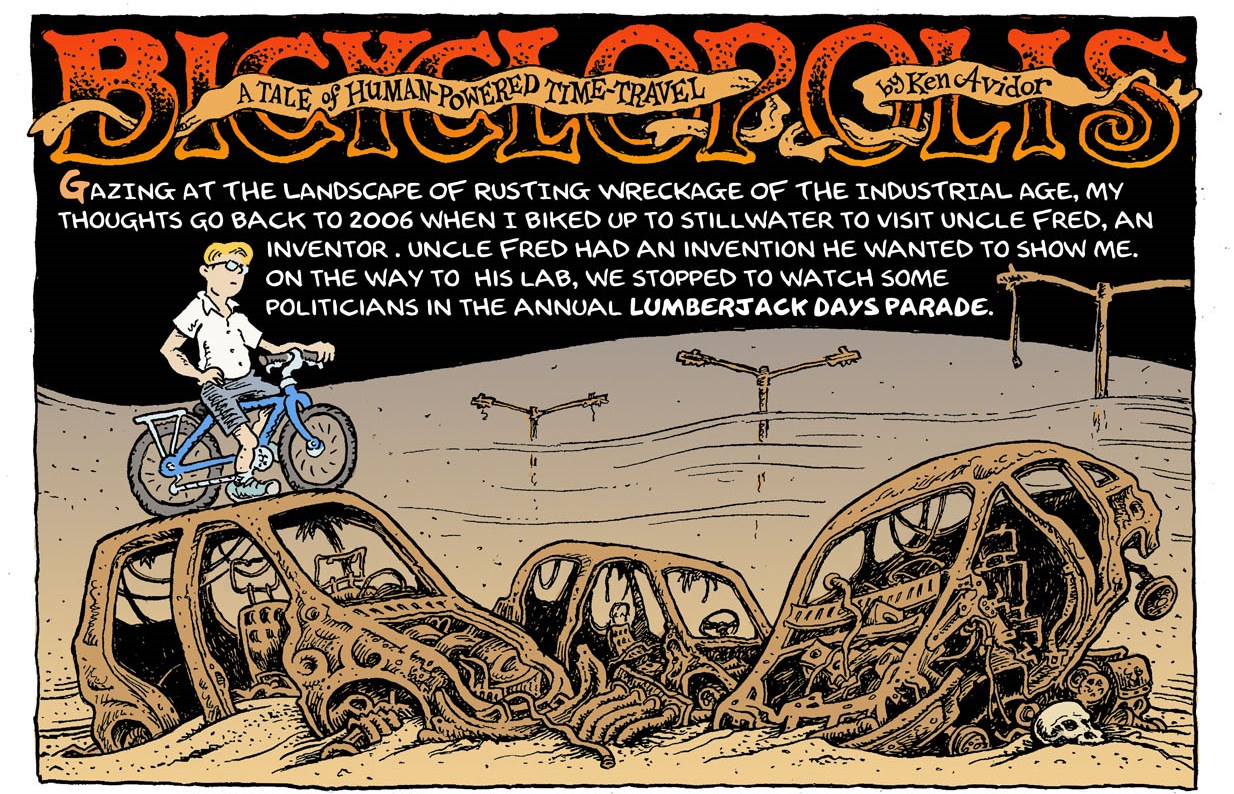

introductionOutside Minnesota, Ken Avidor is one of comics’ most underrated artists to have come of age under the influence of the underground comix boom of the ’60s and ’70s: a veteran of alt-culture periodicals like Punk and Weirdo, he spent his most formative years in New York after the city had become wracked with debt, crime, and — maybe most impressionably — the neighborhood-destroying, city-upending highways planned by Robert Moses. In Minnesota, he’s a dynamic hellraiser: a resident of Minneapolis, and then St. Paul during more recent decades, Avidor’s been contributing to the local alt-comics scene to a major extent, with popular series like bike-advocate favorite Roadkill Bill and his new futurist serial Bicyclopolis using his distinctly textural, busily vibrant style to examine the ways urban spaces and transportation shape our lives and communities. Along with his wife Roberta, Ken has spent much of his time in his adopted hometown laying out the neighborhoods, the topography, and the lifeblood of the Twin Cities as they live and breathe as a metropolitan area, with a deep interest in urban sketching and the visual chronicling of daily-life minutiae. Here are some of the highlights from an extended conversation with the artist.

Nate PatrinTell me a little about the premise of Bicyclopolis — it seems like it ties into your themes of urban living, and how cities can shape the way we see our surroundings.

ken avidorOne of my early influences in this area, when I was a kid, I grew up in the suburbs. And one summer I didn’t have anything in particular to do, which is very suburban. I went to the little library, read through the entire library all the way through the “P” section. That’s where I ran into Robert Caro’s The Power Broker. It’s about Robert Moses, the guy who built all the highways; he started off as this kind of good guy and ended up as this evil guy. There’s a guy, the villain in my book, who shows up at the end of the first book, which I just completed. He’s kind of the embodiment of the Robert Moses character. [The Power Broker] pointed me in the direction of being interested in learning how a built environment was created. We just assume growing up that it’s always been this way: highways, buildings… and the more you learn, you find it wasn’t always that way. In Bicyclopolis I put it all together as where I see it going in the future. Can it continue sustainably? I think most people who are familiar with resource depletion, global warming, overpopulation… they know there’s difficult times ahead. I’m not a scientist, but I’ve done a lot of research on it, and it’s a time-travel story and takes you into a future where a lot of these predictions come true. And it’s usually a worst-case scenario, but that’s what makes it a fun adventure!

I did an earlier version of this book with Roadkill Bill which I drew for The Pulse weekly, and I did just self-contained four-panel things. And then I wanted to do longer stories, and one of them was “Illichville,” based on an imagining of a convivial place — that was Ivan Illich’s term — for a place that where the highest of value was equity. Which is something that people talk a lot about now in terms of income disparity. But also with transportation — as a bike rider, you’re familiar with how little equity there is for pedestrians and bicyclists. And that’s changing, that’s getting a lot better than ten years ago.

npNow you lived in New York for a while, right?

kaYes, I grew up in Westchester, but I lived in New York for a long time.

npIt’s funny that one of the biggest cities in the world is definitely one of the easiest places to live if you choose not to drive, just because of the mass transit and how neighborhoods really feel self-contained.

kaNew York is a great place to bike; it’s better than it used to be. I’ll bike anywhere — St. Paul is not the greatest, but we’ve got the new bike plan, which is awesome, and we’ve got people making change here. I used to live in South Minneapolis, and of course if you compare Minneapolis to St. Paul, people say, “yeah, it’s a better bike town.” But I actually prefer biking in St. Paul as an artist because visually, going up a hill or coming down a hill, the changing levels [of elevation], the vistas change. I get so bored bicycling on the Greenway — which is a wonderful thing, but it is the most boring place for me to bike because you just don’t see anything. It’s like being on a freeway in a car. For a lot of people, it’s the ease of biking… but I’ve got gears on my bike. When I first moved [to St. Paul] it took a little getting used to, but now I just bike up that hill.

Back to Bicyclopolis… it’s still being serialized, and I like doing that because I don’t like to just dump something on somebody. And it’s on streets.mn, which is a great website for people who’re wonky about urban design. It’s not a website for people who aren’t interested in that stuff, but if you are interested in that stuff, it is awesome.

npLike if you have big opinions on the Lake Street KMart space?

kaExactly! But I just love those people, it’s a great website, and they’ve been supportive so I’m happy to have it there.

npWhat is it about the Twin Cities that cultivates bike culture more than most other cities?

kaEverybody has their own theory about that, but my theory is that because of the long, hard winters, they like to attempt the impossible. And something else about the culture — maybe in other places they just accept it’s a horrible winter, and they just drink all winter long. We do that too! But here, also, there’s something about people: gardeners, golfers… they get out there as soon as the snow’s off the golf course. It’s the same with bicycling: “I’m gonna bike all winter long, I don’t care if it’s 40-below. I’m gonna get a fat tire,” and all that stuff.

npI have a theory about the reason for the culture in the Twin Cities: they’re a lot further away from other major metropolitan areas than most other cities are. It’s like an eight-hour drive to Chicago.

kaI think a lot of that creativity comes from that isolation, too. We’re kind of like the Finland of the Midwest. They’re always inventing weird things in Finland. But it’s kind of a different culture — people come here and do amazing things. An interesting thing is, when I started doing comics about bicycling and transportation, there were two other people who did that — Andy Singer and Roger Lootine, who still do that. It was always kind of amazing; I mean, we had [group] shows of our stuff. But why is that? I don’t think you even get that in Holland, even, because their bike culture is mainstream.

npMaybe it’s a reaction to how much the city sprawled in the ’50s and ’60s. After white flight from the city (as with so many cities), and since the suburbs the Twin Cities were designed to be so car-centric — our current bike culture feels like a reaction, like definite and deliberate resistance to the idea that you have to live with a two-hour round-trip commute just to have a job.

kaSomething weird happened here, though, and it didn’t happen in a lot of other cities. Most places put up a bunch of apartment buildings and tore down the [single-family] homes. Here the development just leapfrogged out. You have actual neighborhoods, like you don’t have in a lot of cities, that aren’t that close to downtown. When we moved here in the ’80s, it was affordable. We’ve got a lot of people who can just not be doing things where they have to make a lot of money. It’s changing though, isn’t it? … I think the affordability of it has helped create our bike culture here, too — people who don’t want to spend a lot of money on their transportation. And we also have a great number of really good cartoonists — Brittney Sabo, Kevin Cannon, Zander Cannon, the Cartoonist Conspiracy, Steve Stwalley, Andy Singer, Roger Lootine. Y’know, it’s a great community. What we don’t have, what I wish we had, is something like the Seattle Stranger, which is more supportive of local cartoonists.

np Like a publication or a dedicated outlet, or maybe a publishing house?

kaYeah. We have a lot of people who’re really good, but they have to go outside of the Cities to get that kind of support. That could change. But it’s good that we have a community of cartoonists, for sure.

npYour style is visually recognizable, it really pops out. But I can also see some potential influence… every other cartoonist, especially of a certain age says “I was into Crumb,” or Zap Comix. Were you also into Spain Rodriguez?

kaLove Spain’s stuff. But before that, when I was growing up, my brother worked at the East Village Other. And they had a comics issue called “Gothic Blimp Works,” which was truly awesome. I went up to East Village Other a couple times when my brother worked there, and they had the most amazing bathroom — it was the Sistine Chapel of underground cartoonists. All those guys, like Spain and Crumb and the others, their work was all over the bathroom. And when the paper moved, they just pulverized the bathroom. How sad is that?

npOof, that’d be worth hundreds of thousands today.

kaAnd I worked at Screw, I was an art director there many many years ago, and we had a pretty good bathroom there, too, of our Punk magazine-era cartoonists. But speaking of influences: even earlier than that, I watched a lot of television, read Mad magazine — Wally Wood, who was a native of Minnesota, all the Mad Magazine guys.

npJack Davis?

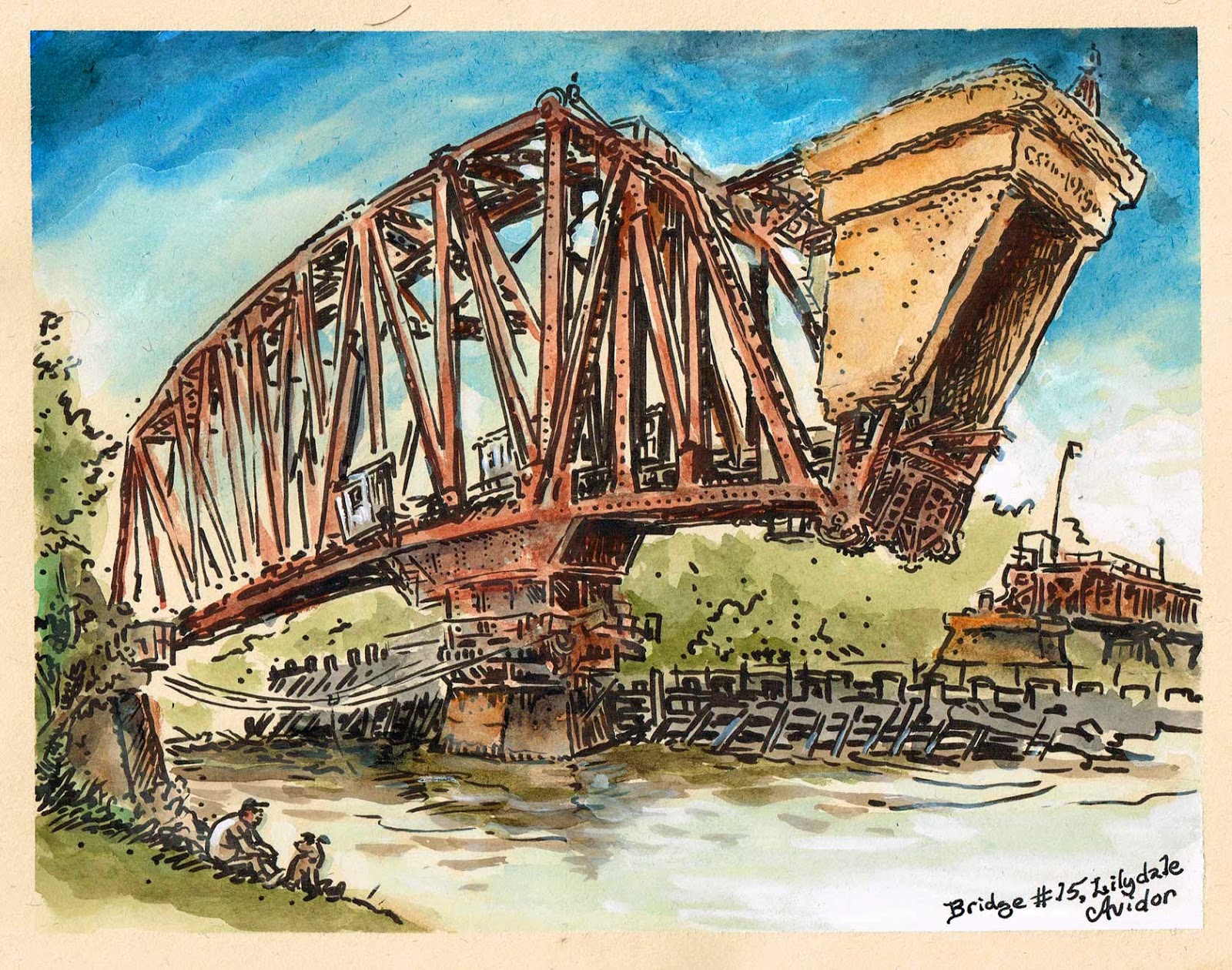

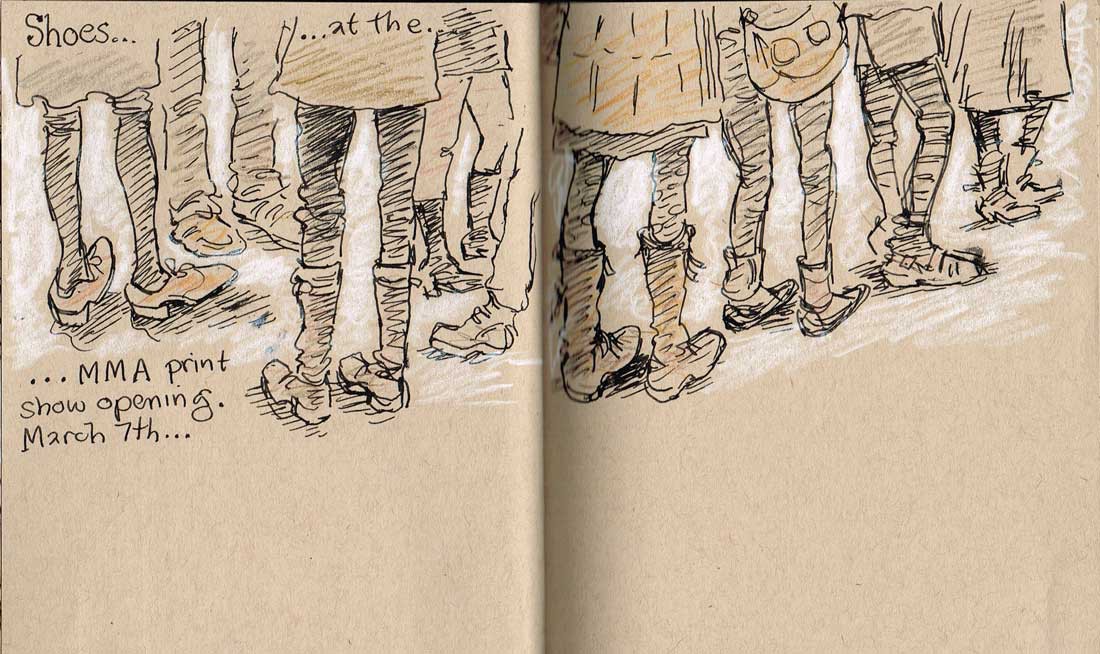

kaOh yeah. Absolutely. So, those were early on, and watching cartoons on TV, Paul Terry’s stuff, and Rocky & Bullwinkle — a lot of that influenced the underground, too. But really more than that is artists like — and this is really more the influence for Bicyclopolis — Eric Sloane, who’s not a cartoonist, but he visualized colonial America. I just pored over [his work]. And if you’re familiar with Lynd Ward, [he did] the original graphic novels, two of them — one of them’s called Madman’s Drum, and the other one is Gods’ Man, the more famous one. If there’s a kind of fine art influence in my stuff, that’s where it comes from. And also [Roberta and I] sketch a lot. A lot of it is just sketching from life. So Bicyclopolis is just how things look. I sketch everywhere.

npI noticed you have a real knack for capturing lots of fiddly details on buildings or machinery, details that might just fade into the background in other artists’ work.

kaIt’s really important to me, and my wife too, to keep up to date. Everything changes, and if you don’t have that visual vernacular — exactly how somebody holds a cell phone, or the particular type of clothing people are wearing — your sketch doesn’t have that ring of truth, and that’s really important to me. There’s an element of satire in Bicyclopolis, a satire of the modern age. When you [get that], it feels really good, it’s like hitting the sweet spot. You gotta sketch a lot to do that.

Related links and information: Find more about Ken Avidor and see more of his work on his website. Read his 10-part, serialized graphic novel, Bicyclopolis, on streets.mn.