The United States of Han

Poet Su Hwang digs into the influence of han in her Korean lineage, the kickassery of untranslatable words into English, and the toxicity of white gatekeeping in the arts––and ultimately delivers an ode to crazy dreams coming true anyway.

My artistic practice (and probably this essay––whatever this is) can best be described as gelatinous: it’s amorphous, messy, mostly transparent, and saltyAF. The one surefire thing that’s given my work any semblance of structure or form is rage. That’s right––pure, unadulterated rage; so much so, it’s been hard to harness it for creative good.

Rage needs to stew and is best served straight up––and let’s just say my rage has been stewing a long, long…long time. And when I say time, I don’t mean in linear terms, like within the context of my forty-four turns around the sun. I’m talking astrotime, baby! Ancestral, spiritual, multi-dimensional time––time we feel in our gut from the base of the spine to our very crown. I wish my younger self could have shared this sentiment instead of wasting nearly two decades imbued with a sense of (conjured) failure, but things manifest when it’s time––stay with me here. I believe some in the literary world (or any artistic pursuit) call this “imposter syndrome,” but my anxiety was fueled by inaction––the worst kind of self-doubt (but something not entirely of my own doing I’ve come to realize in recent years). I’m looking at you: white heteropatriarchy supremacy! Add to this a kind of cultural inertia, han, and we’ve got ourselves one spicyass, inedible stew.

In the early 1980s, I started learning how to speak English (while forgetting Korean) when I was eight years old, and from what I remember, it was a mixed-bag experience. Some kids were nice, some were not; some teachers were nice, some were not.

I suppose this made me interested in words without direct English translations as I got older––concepts or states of being that are endemic to a unique place and time. Words like duende (shout-out to Ray Gonzalez), toska, litost, wabi-sabi, saudade… They simply do not have a mirror in English because they are myths based on the full spectrum of emotions borne out of history, trauma, and ultimately redemption––channeling our ancestral past lives in fits and starts over generations. Perhaps the language of colonizers = difficult time with such nuance and empathy? There are hundreds of such words from around the world, but the ones I’m drawn to most describe an indelible melancholia mixed with a steadfast resolve for justice and balance.

Han, in that respect, is no different.

All things Korean have been the rage lately in American social media discourse like snail moisturizers and BB creams, K-Pop (BTS, who knew? #okofficiallyold), tableside BBQ, kimchee, the plastic surgery epidemic, and an intense, global soap opera following––but we can’t really discuss Korean history, culture, and the arts without talking about han.

Han describes a key intrinsic characteristic of being Korean. A Koreanness, if you will––there’s even a

Wikipedia page! Han more or less means “sorrow, regret, grief, resentment, a dull ache of the soul.” There is also a kind of beauty in the sadness––a quiet inner drive toward salvation. Google it.

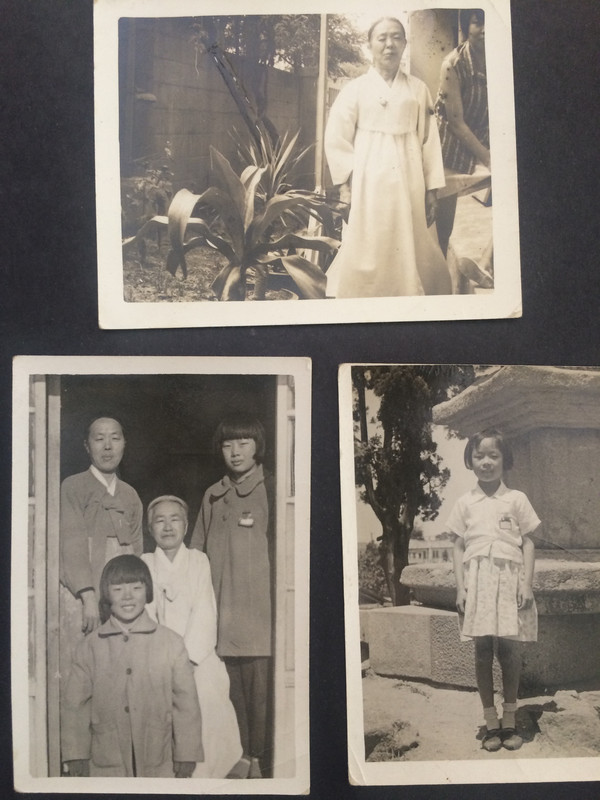

My mom used to say that our history is built on tears––not just from the civil war that ravaged then split the country in half when she was a young child, but also centuries of invasion, oppression, and attempted colonization from our more aggressive neighbors. My paternal grandfather wrote at length about surviving the Japanese occupation––a period when speaking or writing in our native tongue was prohibited and cruelly enforced (my other grandfather was taken one night during our civil war and never returned; yes, my entire family is technically from the “north”––an American construct, but I digress). It was in fact during the occupation that han came into being––rather, was given a name. One of my favorite explorations into han is by the late/great Anthony Bourdain in an episode of Parts Unknown.

I read somewhere han came into the American lexicon from the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. I was a teenager then and I still recall its personal and collective impact.

Growing up, my parents ran a dry cleaners, then a small corner store, in the Queensbridge Projects in NYC. I witnessed firsthand the blatant assault and oppression of black and immigrant communities by white supremacy, primarily in the form of police (aka mass incarceration), as well as mounting tensions and marginalization within marginalized communities due to cultural differences and obvious language barriers. And fear. We were and continue to be bound by fear. The Riots highlighted the fractured relationship between Korean merchants and their black customers, when the reality was/is that white supremacy pits people of color against one another by pulling on our survival strings until we’re all tangled into knots.

I don’t take for granted that not so long ago, we didn’t have the ability to say/type words and phrases like white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, gaslighting, #MeToo, etc. Words are terribly important, now more than ever.

Bodega is a Spanish word that has several meanings, but its primary definition is “warehouse or cellar.” In NYC, the word has come to describe a world within a world: a corner mini-mart that serves the community within a several-block radius. Like all good things, however, bodegas are now an endangered species.

This October, my debut poetry collection BODEGA is forthcoming with Milkweed Editions. I had the title for my book before I wrote a single poem because this one word holds so much power, meaning––and memories. BODEGA uses the metaphor of this urban, communal space to interrogate issues of race, identity, im/migration, and marginalization within marginalized communities from the lens of a coming-of-age story.

“Before wanting to be a poet I did many things: worked hateful low-paying jobs, lived in a lot of group houses, took up the flute, read, drank, took drugs, found my way in and out of friendships and love relationships. My life didn’t change once I discovered poetry. But I had found my direction. I didn’t have a great aptitude––my early poems were truly terrible––but I had a calling at last. I realized that poetry was my gift. My ‘genius.’”

Kim Addonizio, Ordinary Genius

When I arrived in Minneapolis in the fall of 2013 by way of Seoul, NYC, then San Francisco/Oakland, I was 38 years young and had been writing poems for about a year. I was the third oldest in my cohort of 12 writers: three came straight out of undergrad and the rest were in their mid-twenties. I was the only person of color. Yes, that’s right, the only person of color.

I was intimidated, however subconsciously. I’m not book smart and my memory is shot. I rarely spoke in class because the last time I was in an academic setting was in the late 90s and I’d smoked a ton of pot since then––plus, I have a hell of a time articulating my thoughts into cohesive words on the fly (hello, INFP curse). As a self-proclaimed failed fiction writer, I was insecure about my writing and feedback to my peers because I had found poetry almost by accident, and I was here to listen and learn.

In light of everything, perhaps the most important lesson of all has been to trust my own instincts (han) while not to take any shit from those swimming in white privilege.

At the start of my third year, our MFA thesis advisor (a straight white cishet male a year younger than I was) berated/shamed me in front of my all-white cohort for the misuse of the word fanfare in a sample draft of a poem. It wasn’t supposed to be a workshop, but rather an informal session to propose our final thesis projects for review. Mind you, my skewering followed my white male classmate’s presentation for a collection of humorous flash essays that would be best enjoyed while on the loo. Yes, he’s a really funny guy, and no, I’m not joking. Our so-called “mentor” thought the thesis proposal was delightful.

When it came my turn, he went on to criticize my use of interrogate to talk about race––saying the word was “tired in post-racial America.” This was the fall of 2015––a year after Ferguson and a year before Trump’s election. I kept it together until my cohort took me to Liquor Lyle’s to celebrate what was then my 41st birthday. I wept by the pinball machine in a swirl of whiskey, shock, embarrassment and yes, rage. If I had been much younger or more impressionable as a writer, who knows what would have (or not) come of the book.

Long story short: I dropped him from my thesis committee the next day, filed a complaint (not the first and certainly not the last), and lit a raging fire in my belly (han). Sadly, my experience with toxic male mentorship in the literary (or any creative pursuit––hell, any pursuit) is totally and completely unremarkable. This retelling is mostly anecdotal, but we can no longer let this behavior slide in our daily interactions. No more staying tight-lipped in the moment for the sake of civility to appease whiteness or the patriarchy. I get it, it’s fucking hard when there are misguided gatekeepers in an inherently subjective field, but whenever possible, it’s important to take your power back. Also, read poet Claudia Rankine’s searing keynote speech at AWP a few years ago about racism in creative writing. Your mentors should be in the service of helping you grow and improve, not take swipes at your writing sea legs. If your mentor sucks, find a new one. Better yet, mentor yourself. Seek advice from people who got your back, then trust your own voice, because each of us are unique and exquisite––and no one else can tell your story.

Four years to the day I cried into my drink on my birthday because of some clueless white dude––on October 5, 2019, I will celebrate the birth of my first book with my soul family.

I’ve for sure had my share of some hot-mess moments/outbursts since Trump, but after a much needed holidaze cleanse, my strangely awesome YouTube rabbithole/spiritual awakening has put a lot into perspective. Basically: always come from a place of unconditional love, but also, always punch a Nazi in the face with your third eye or whatever you want to call it.

I have many lessons yet to learn––I know I will never know enough and I’m totally fine with it. If anything, I don’t know anything anymore. All I can do is trust my han, and yes, karma.

If you’re in academia or are planning on it, don’t sweat it. Get what you need, finish your business, then go out into the world and kick some serious ass! Find your tribe(s)––relationships you’ve intentionally created. Seek out minds that vibe with your frequency and you’ll see how good things start to manifest. Also, remember things take time, so just keep your head down and do the work. Then rest. And definitely play––don’t forget the joy of this shit because we’re here for a blink, then we’re stardust again.

Cultivate the type of creative community you want and always remember you reap what you sow. So yeah, be kind without being a doormat. Respect your ancestors and your work. And go hug a tree, seriously.

I’ll end this rambler with two simple words for marginalized writers/artists immersed in toxicity and negativity: Rage responsibly. And may the han be with you.

This piece was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Saymoukda Duangphouxay Vongsay.