The Return of Analog Film in a Digital Age

On a resurgence of the analog in photography and filmmaking, and the local artists who have been sustaining these tactile practices within a society that relies heavily on digital technologies

On a clear summer night on Memorial Day weekend in 2015, nearly 200 people showed up at the Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery with assorted blankets and chairs and seated themselves among rows of 18th century historic gravestones. They had come to Minnneapolis’ oldest cemetery’s open lawn space for a screening of Buster Keaton’s classic silent film The Navigator. The film had been originally shot on 35mm nearly a century ago. The local band Dreamland Faces played a live score.

The man behind the screening was Trylon Cinema lead film programmer and film collector John Moret, who had set up the scaled-down portable screen and projector that night for a screening designed to raise money to restore the vandalized limestone pier fence on the cemetery’s perimeters.

But Moret’s reach into 35mm film was not incidental. For the past seven years, he has regularly programmed and screened numerous analog films, whether at the century-old cemetery site or in a dark, quaint cinema projection booth. In an effort to cultivate a community of film lovers, he continues the practice of screening all types of analog films, despite the widespread consumption of digital media nowadays.

Analog film isn’t just a unique part of our collective history, it also remains a vital practice cherished by many. Its recent resurgence serves as a reminder that analog film is here to stay within our current times in both realms of filmmaking and photography.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

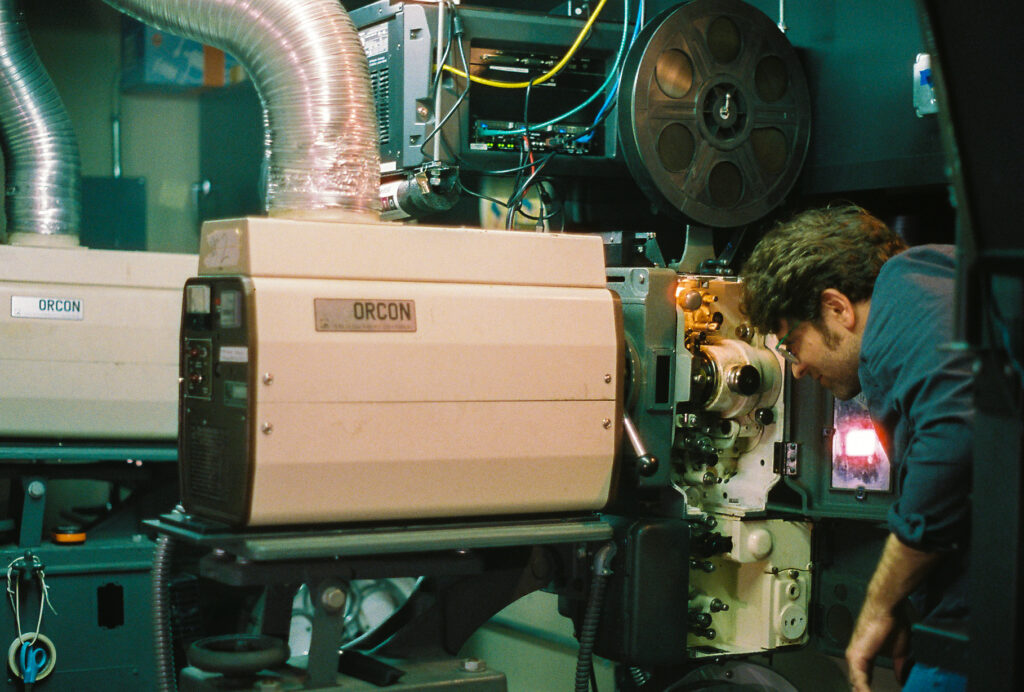

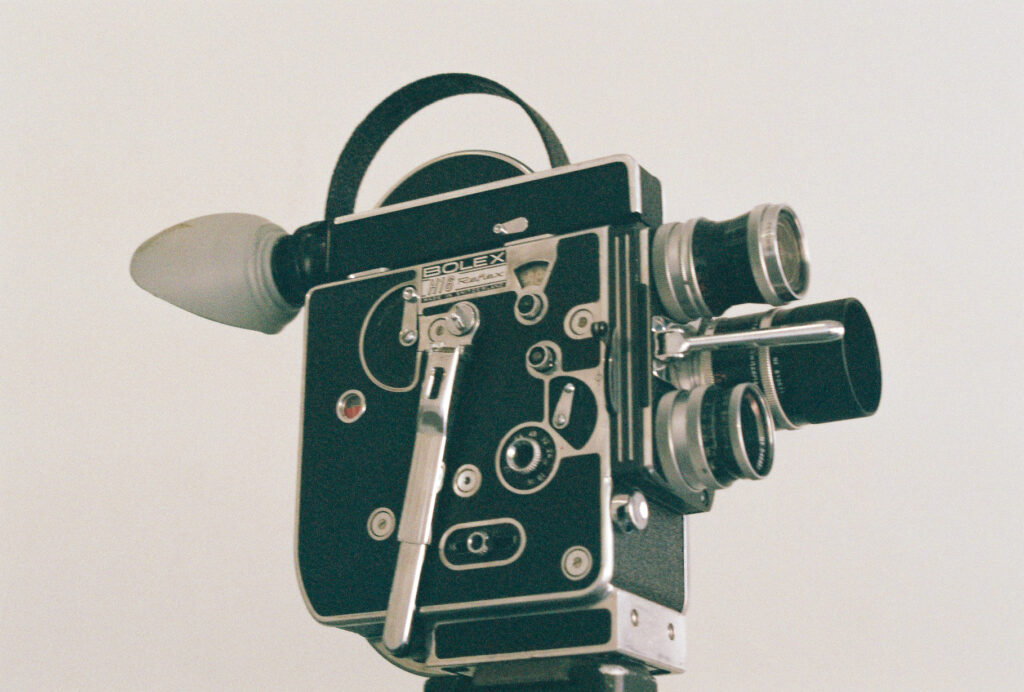

On a weekly basis, Moret and Nikki Weispfenning, Trylon cinema manager and projectionist, spend their time screening in the small projection booth of the Trylon cinema, in close proximity to two large, bulky Century analog film projectors and Orcon lamphouses, each relic dating back nearly a century. The two projectors and lamphouses take up nearly a third of the room’s square footage, in contrast to the sleek, digital hard drive and monitor lying beside on a small shelf.

They represent a hold-out of sorts within film, keeping its heritage and practice alive within a society that relies heavily on digital technologies. Analog film has been steadily increasing among consumers. It recently gained popularity among younger filmmakers and photographers, but the practice drags because of the time and money it requires. In a tsunami of digital images we consume every day, the physicality of analog or celluloid-based film is what makes film what it is—a core tenet of our sensory experience. It’s not a series of zeros and ones on our devices’ screens. Quite the opposite: it’s tangible.

Sarah Sampedro, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Sarah Sampedro, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

“Living in the digital world, our actual physicality is getting starved. We want to look at things with more robust color space. We want a more full-body experience,” University of Minnesota art professor and photographer Sarah Sampedro, said.

To Moret, the experience of analog is indeed a physical thing. Film stimulates a tactile sensation. You can hold onto it. You can see the effects of age and usage on a strip. You can observe the passage of time every time you run film through a projector with its imperfections. There’s dust, dirt, and graininess to film. A film strip has gelatin in it, a natural animal byproduct. It scratches just like our bodies do. It decays like our bodies do. You can witness the fading of color on an acetate film print from the 70s as it goes through the projector’s gate—the film strip loses its blues, reds and greens, and then tends to turn to pink. Whereas the same digital image remains somewhere in a digital verse, achieving perhaps a level of perfection that’s inorganic and inhuman-like.

“It’s such a performance, but it’s also an experience that’s actually moving through the projector, and every time you play it, it’s dying. But if you don’t play it, it dies anyway because that can’t save it,” Moret said. “It’s not ethereal. It’s not somewhere in the cloud. It’s a physical piece.”

Sam Hoolihan, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Sam Hoolihan, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

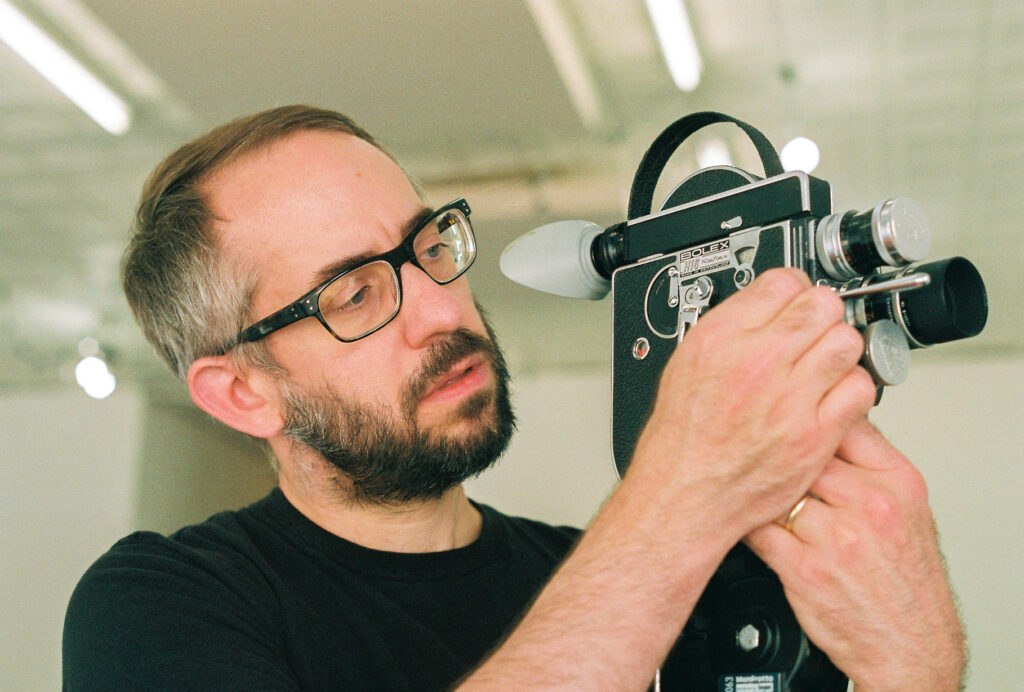

University of Minnesota art professor and visual artist Sam Hoolihan has taught Super 8 and 16mm filmmaking for nearly a decade. At the end of each class project, he encourages his students to gather and screen their short films in a dark room, not only for the communal experience—something that’s slowly becoming rare in a largely digitized age—but for its visual and aural aesthetics.

“It’s really hypnotic. There’s a visual quality to this kind of projected, moving image that’s softer on the eyes. It’s not so fatiguing,” Hoolihan said. “If I’m watching something on a streaming service for a couple hours on a laptop, my eyes get so tired.”

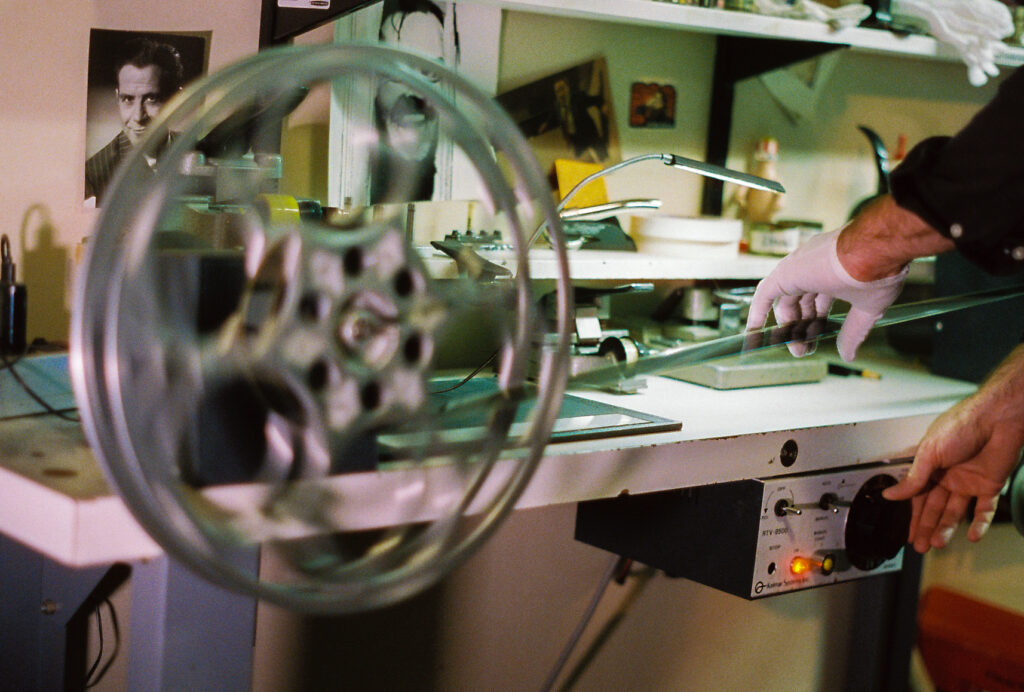

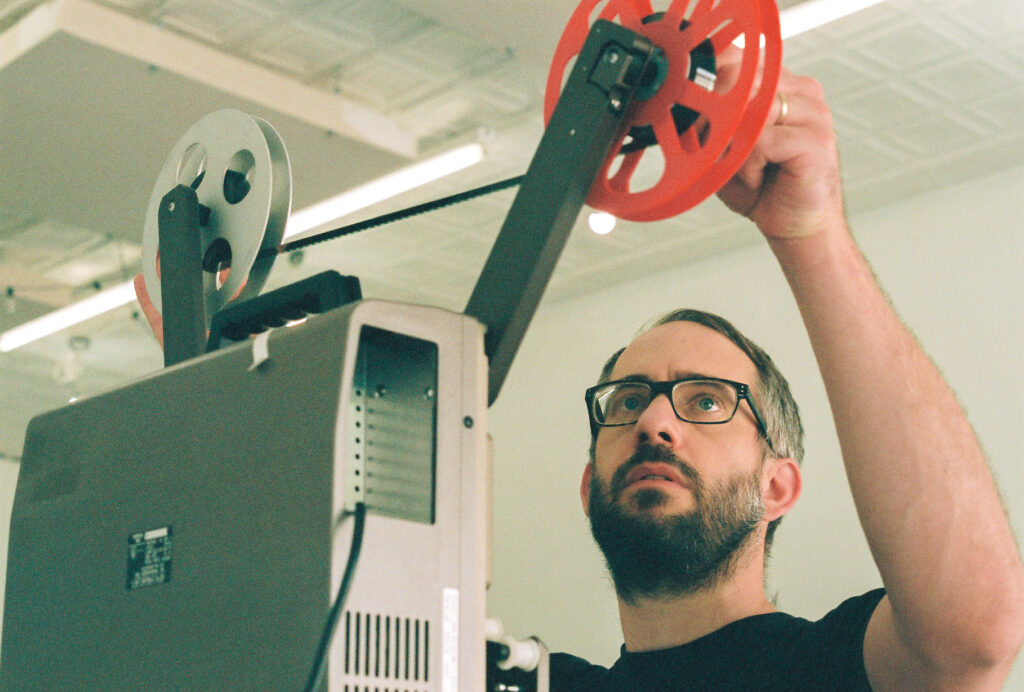

On a recent Sunday night at the Trylon cinema, two large hexagonal-shaped containers sat in the corner of the projection booth, each weighing 35 pounds and held three to four circular reels of Alfred Hitchock’s Torn Curtain polyester film print from the 90s. With screening analog film, you can’t simply push the start button and wish for things to magically appear on screen. There’s a lot of effort and time put behind the scenes.

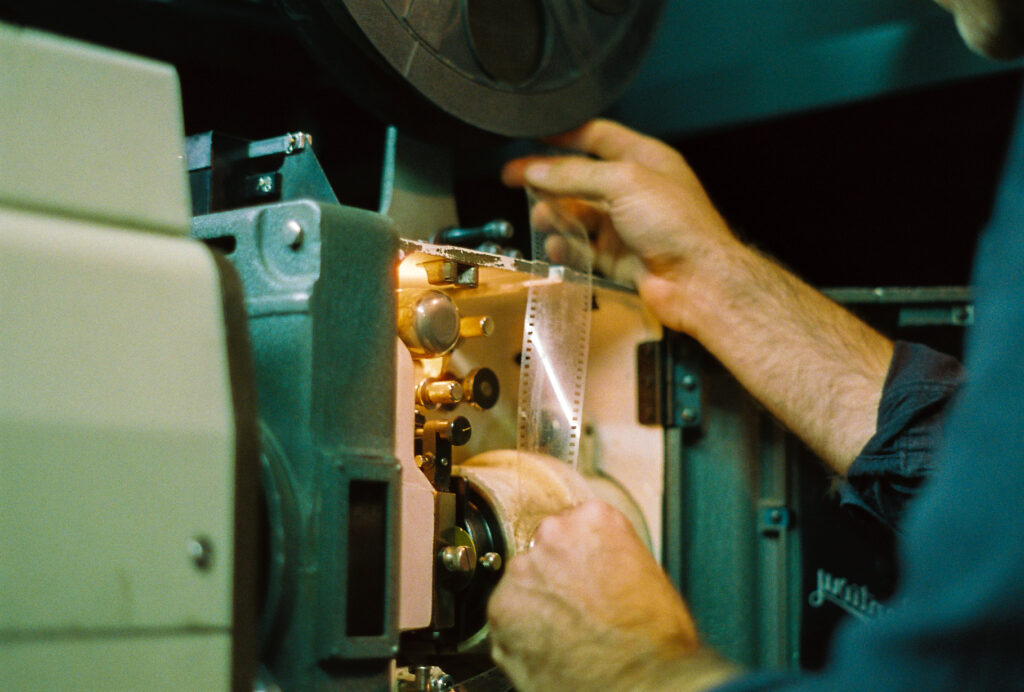

Weispfenning wound and rewound the seven plastic reels onto sturdy metal reels and filed them in numerical order. She inserted the first film reel onto the grand projector and installed the take-up reel above the projector. Gently holding the tip of the 35mm film strip with her thumb and index finger, Weispfenning rolled out the film through an intricate pathway—threading the film strip onto a slot-in roller, passing through the gate—a rectangular opening where the film is exposed to light—and continuing the motion along the track laid down by other rollers. This resulted in a conveyor belt motion inside the projector. Weispfenning started the motor switch and lifted the lamphouse’s metal douser blade, which allowed for light to shine onto each film’s frame. The grainy numbers slowly faded on screen: three, two, one—showtime.

The film’s projection reflected onto Weispfenning’s glasses, as she stood firmly by the projector with arms crossed. She looked through the square-shaped glass window, ensuring that the film ran smoothly. She repeated this ritual of threading and additionally rewinding six more times, back and forth between the two projectors. The audience seated in the last row could hear the humming of the projector’s motor and the clinking of the film reels.

Celluloid-based film is mostly about the process and the relationship between film and its user. Nothing is automated. There’s no room for passivity, only room for precision. The user must take an active role working with film, or else with the smallest mishap—perish the thought—the film strip might be damaged and unretrievable.

With film, the user is always making choices, whether it’s picking the type of film stock or film format. By shooting on film, you’re forced to slow down. You have a limited roll of film of 36 exposures for a 35mm photography camera before you have to rewind and insert a new roll. By not seeing the thumbnail as one would see on a typical digital camera screen, you don’t receive the immediate gratification and are forced to embrace the process. There’s more intentionality—you have to pause, look through the camera’s lens at your subject, and adjust technical and stylistic features, such as composition or aperture, before pulling onto the shutter release cable and clicking the button to shoot or record.

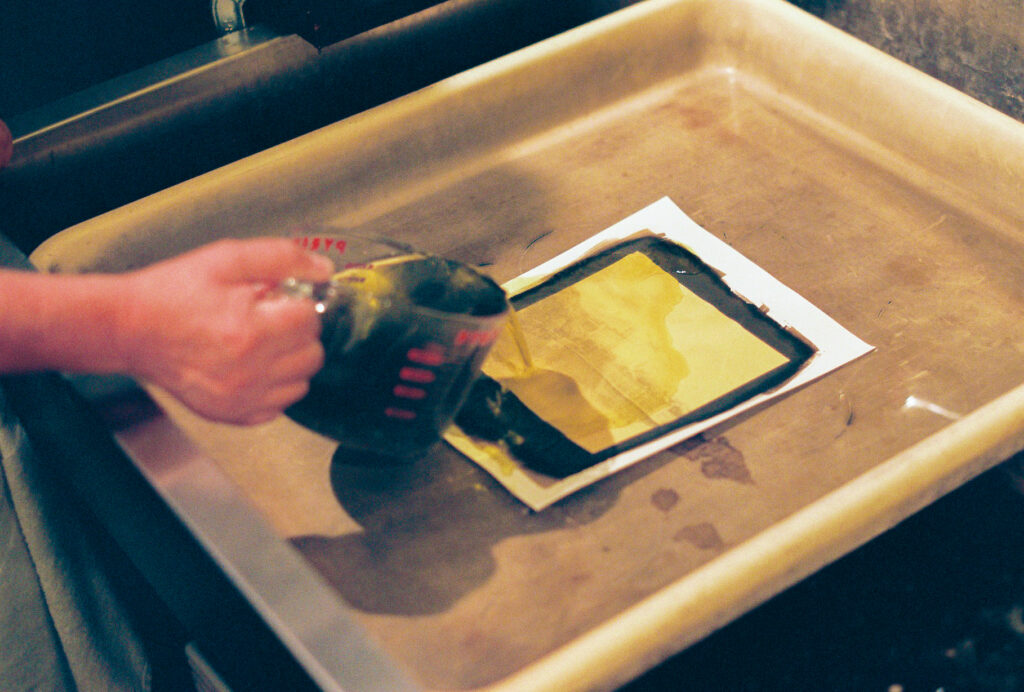

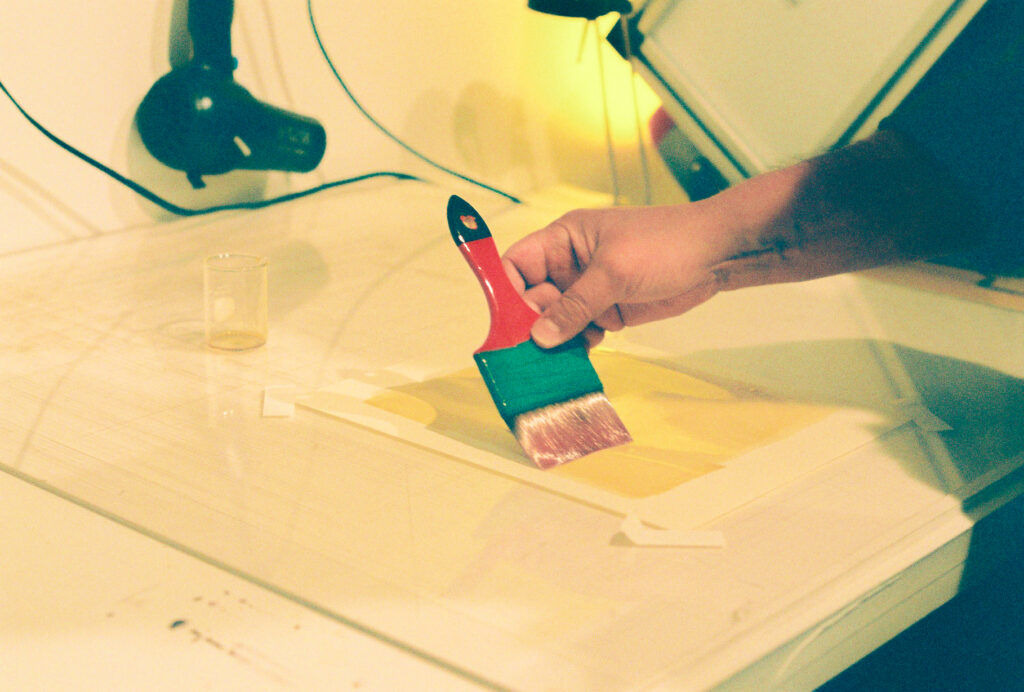

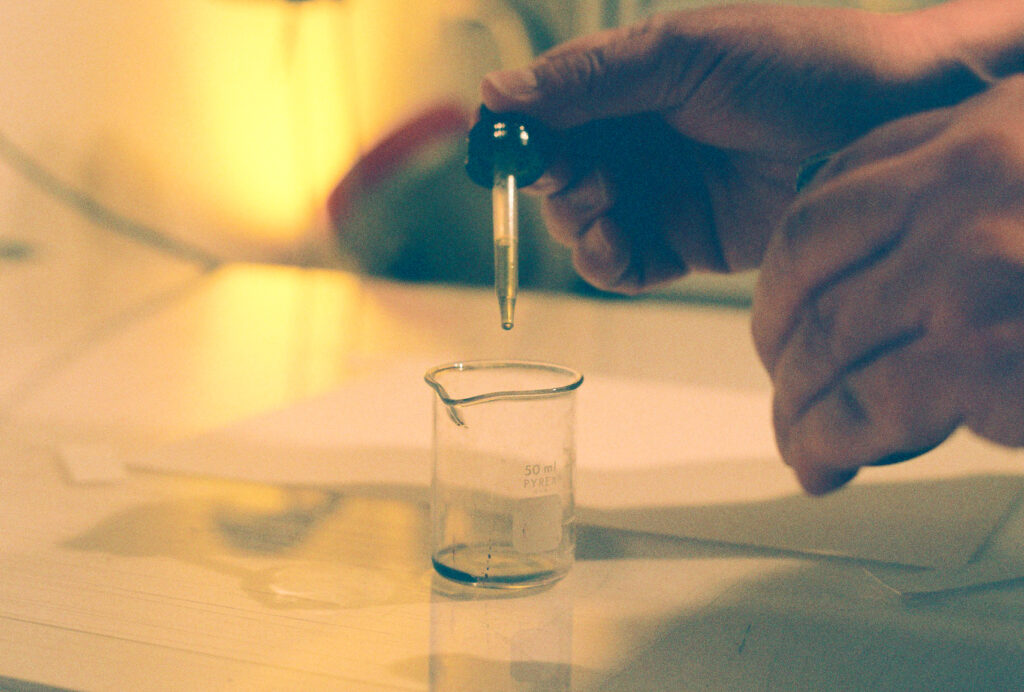

Dealing with analog film can be time-consuming. The majority of the time is spent behind the scenes in a darkroom, mixing certain combinations of chemicals for the developing and printing processes of film. All that can take hours.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Keith Taylor, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Keith Taylor, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

Keith Taylor, 2022. Photo: Ray Shehadeh.

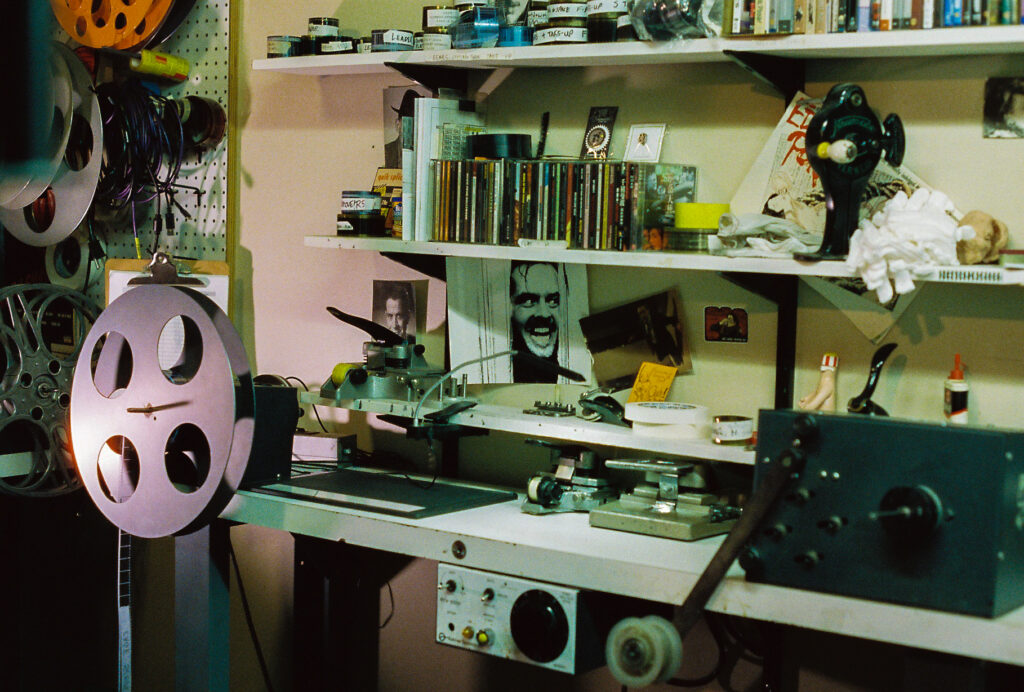

On most days, Keith Taylor, a film photographer and educator specialized in historical photographic printing processes, can be found in his quaint studio and darkroom in North Minneapolis. He has mastered the processes of platinum palladium, polymer photogravure, and silver gelatin.

In his darkroom on a typical Monday afternoon, Taylor mixed specific ratios of droplets of platinum, palladium, ferric oxalate, and NA2. Using a large bristle brush, Taylor then coated the light-sensitive emulsion onto the paper and waited for it to dry. He placed the film negative on top of the coated paper in a controlled UV exposure box and waited nearly a few minutes to let the magic of chemistry do its work. A faint, latent image appeared on the marigold-colored coated paper. Quickly pouring the developer onto the paper, the print appeared in a wide, sharp tonal range of blacks and whites. The tree leaves and grassy hillside found in the print materialized in great detail.

“The ability to create something by hand—it’s relaxing,” Taylor said. “With film photography, that’s all in the darkroom. It’s very therapeutic. Even retouching prints, spotting prints, you sit there—you’re in a world of your own.”

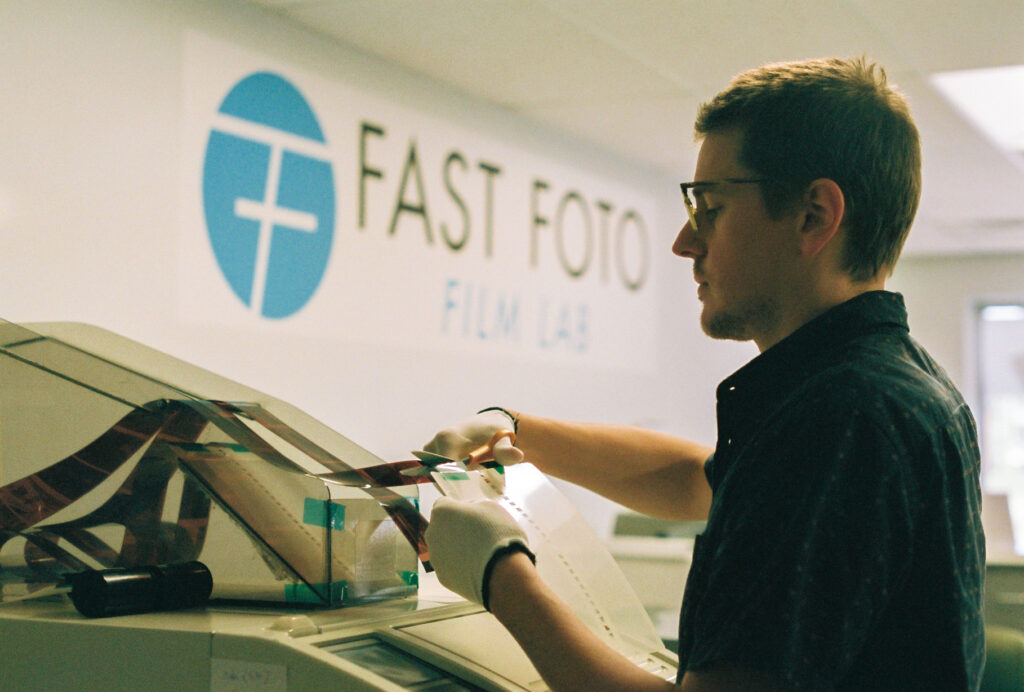

The resurgence of film has surprisingly gained popularity among a younger age group, as more than two-thirds of younger people shot more film than digital, in comparison to more than half of those above the age of 45. Yet, with growing demand among a younger demographic, costs rose as well. Until recently, prices for film products experienced an increase by 30% and additional price hike of 20% across distributors. Such expenses constitute film cameras, film stock, and the chemicals, tools, and equipment that are used for the processing and printing of film.

“It’s become a trifecta of pandemic, supply and demand, and aging film factories,” Thom Abbott, marketing and film technician at Fast Foto Film Lab, said. “Everything is expensive for whatever reason, whether it’s materials, manufacturing, or just nowadays, the pandemic and shipping costs.”

Even though film cameras are slowly becoming obsolete, the entry to film isn’t as harsh on the bank. Rather than spending nearly a thousand dollars or more on a digital camera, film cameras could be found on eBay as cheap as $40.

“The younger generation really is drawn to the analog because they’re tired of the cycle of always having to buy a camera and then updating,” said Sampedro, who has taught digital and film photography at the University of Minnesota for the past four years. “This commodity- and consumer-based culture of ‘always more, always new,’ is exhausting.”

The older proponents of analog are hoping to use analog film’s big advantage over digital as its best asset: its archival qualities. In 2022, we’re still able to access and watch Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden, the oldest surviving silent film from 1888. Archivists recommend that for the longevity of moving images, it’s best to have a film print made.

“There are some filmmakers that are completely digital, but they make a film print and they put that in the archive,” Hoolihan said. “Is a hard drive from 2009 going to last until 2050? How many times are we going to have to then migrate that digital code to the next without loss of quality?”

In an effort to sustain surviving analog film prints, Moret and three of his friends have been running the Cult Film Collective. The film group started six years ago as a way to overcome difficulties encountered with exhibition rights and obtaining rare film prints. Since then, it has intentionally focused on making 16mm and 35mm film screenings accessible to the public, ranging from screenings of the 1970s New Hollywood to classic horror to kung fu.

Recently, the majority, if not all, of analog screen theaters have been replaced by digital forms. Moret has a sense of responsibility in continuing the practice of screening analog film and diversifying what the viewer sees to instill appreciation, not only for other cultures and people, but also other time periods, and most importantly, the medium itself.

“We’re always dredging up the past. We’re constantly keeping it in front of people’s faces. They’re watching movies from 100 years ago, and they’re watching movies from 10 years ago,” Moret said. “It’s really important that we don’t feel disconnected from ourselves.”