The Music of Woodcarving

Filmmaker Deb Wallwork offers an evocative essay in response to Fergus Falls artist Charles Beck's gorgeous woodcut landscapes.

I had heard rumors about the house he build, that it spanned a little canyon. On the wrong side of the tracks in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, we drive past homes patched together from peeling paint, and climb up through the cement factory’s back lot. At the top of the hill, there’s a silver mailbox: C. Beck. A trail of faded wood steps carries one through the woods, over a ravine, and then, by extension, the path becomes a bridge becomes a porch which the snow has lightly dusted.

There, between curtains of firs, is a driftwood colored Bauhaus-style house. A life-sized wooden caroler sings from a gilded hymnbook next to the welcome mat.

Charlie Beck comes to the door in a faded flannel shirt, white hair in a flame around his head. He has the freckled complexion of a farm boy—faded, dappled, softened, and wrinkled into a pale chamois. He offers to bring us in for coffee, then changes his mind, and takes us to the studio instead.

At first glance, it is dim. It is much like any garage workshop in rural Minnesota, where cluttered work benches are pigeonholed with drawers, and punctured boards on the wall hold hooks for hanging tools. Stacks of old phone books sit on the desktop, along with paint drips, scattered quarter-inch nails, and wood shavings.

A red-and-black-checked lumber jacket hangs on a ladder-back chair. Duck decoys in various stages of disrepair congregate on a shelf, some with only a wire stump where the head has broken off.

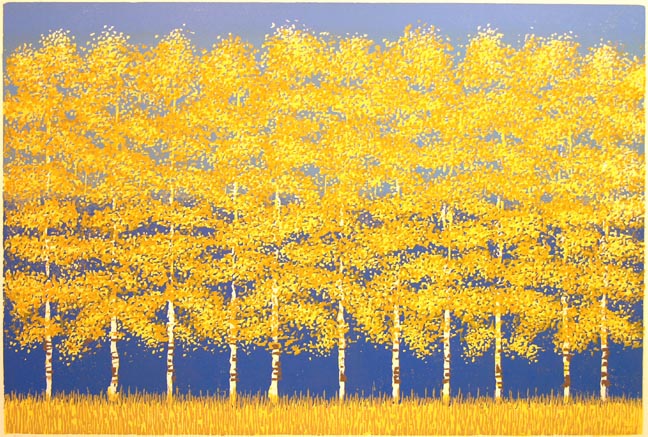

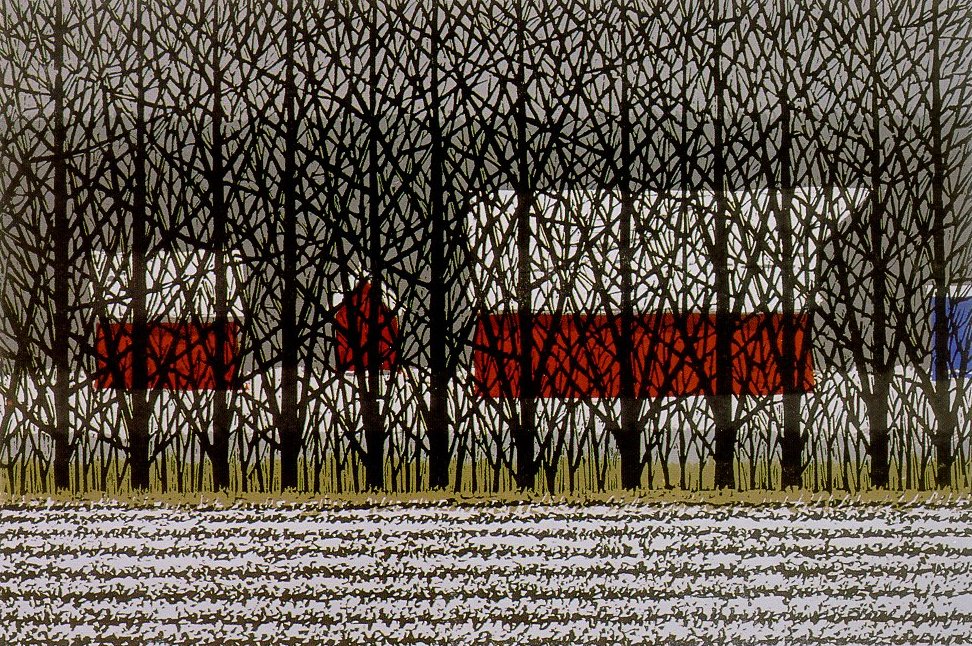

Here, at the end of this room, the roof suddenly rises up, and light from a skylight spills down like God’s finger. It illuminates, on a battered easel, a single woodcut print of winter poplars: a pattern of notched trunks. This is the road less taken, shadowed and stately, where, between the crisscrossed branches, tiny panes of light glint and glimmer.

The image crackles like wood on fire. Down at the bottom, little cuts multiply into a frenzy and dissolve perfectly into a dusting of snow under trees. Early winter, the newly fallen white page is calligraphed by clipped tips of curled up dead leaves. Only later do I see another block where, on the edge facing out, he’s written “Cathedral”.

“It still needs a little salt and pepper. A sprinkle of this or that,” Charlie says.

He likes to talk about process: “If it isn’t working, I just set it aside for a few days and come back to it. I wait until a solution occurs to me. I never force it.”

“Some people,” he says, “want work that’s realistic.” Or expect prints more meticulously registered.

“There are those who like to point out the flaws. And I tell them,” this 84-year-old master printmaker says, “I make a lot of mistakes.” He laughs. “The mistakes belong to it. They’re marvelous!”

I know what he means. It happens in editing film, too. Happy accidents. Chance breaks you out of old patterns, gives you gifts you’d never expect.

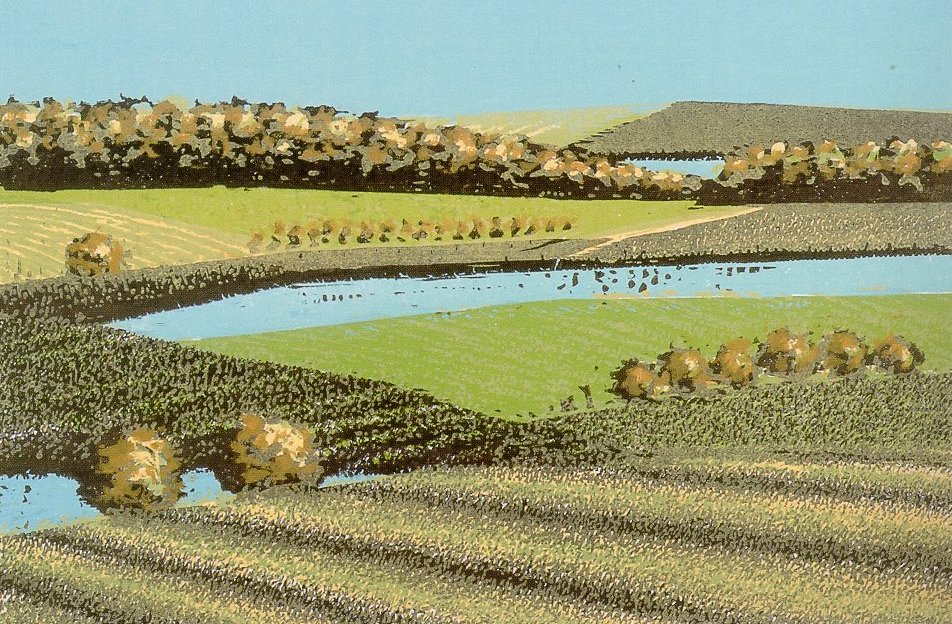

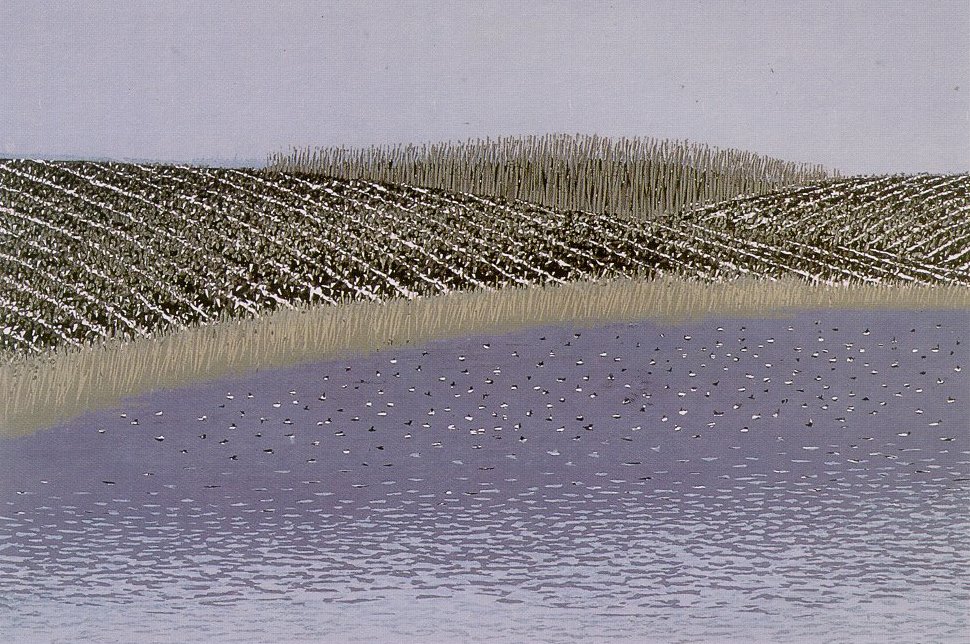

Of all the seasons, he likes late fall, he says. Transitional, liminal moments when everything is in flux.

I begin to see him as a hunter.

A man who designed a house so that the outside world echoes within. He’s a scavenger. A wild card. A modest soul. Not so different, on the surface, than his deer-hunting, farming, small-town neighbors. As professor Mark Strand put it, Charlie Beck is “a modernist in regionalist camouflage.”

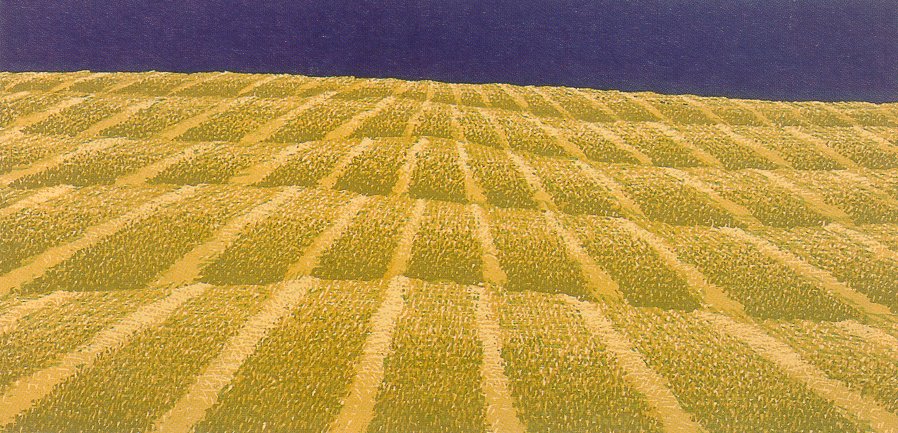

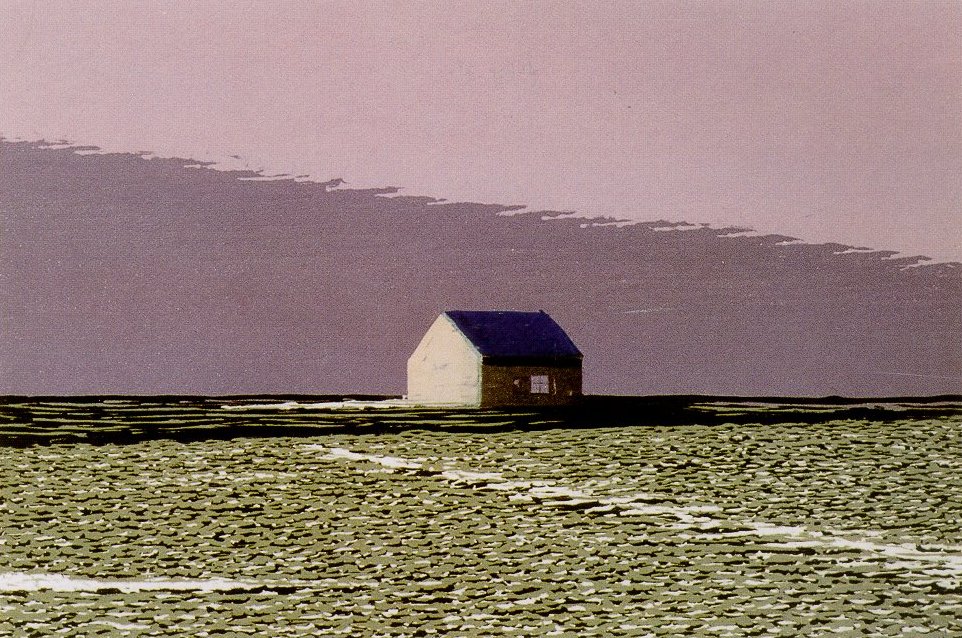

In the autumn, after the leaves darken and fall, the land is more vulnerable and color becomes subtle: open fields of turned earth, the startle of a cloud, wisps of snow between the great skeletons of trees.

Quarreling geese resolve on point, and the ancient gilded light lingers over bent grasses.

“It’s this,” he waves his hand at the world around him: the trees, the fields, the little barns on hills. “It’s a feast.”

Some might wonder how he can survive, as an artist, in this distant corner of the world.

“The temptation” to art, he says, “is everywhere.”

About the writer: Deb Wallwork is is an artist, writer, and documentary filmmaker. Best known for a series of videos on Native American culture, Wallwork has received national awards and had her work screened in film festivals and on PBS. Her short film on Charles Beck, entitled simply C. Beck and co-directed with another Minnesota filmmaker Mike Hazard, just won ITVS‘s Independent Lens Online Shorts film festival. Visit Red Eye Video’s website for more information on Deb Wallwork’s current and upcoming projects.