Studio Chronicles

Critic Corinna Kirsch looks closely at Aaron Van Dyke's new works, photograms and abstract paintings that "function as documents of the artist's studio practice" -- on view in Bethel University's Olson Gallery through March 28.

IN GRADUATE SCHOOL, I ONCE TOOK A CLASS with a professor who, on a regular basis, would take us to a museum and then split up the students into various groups, sometimes based on an art historian from that week’s readings-”Team Krauss” and “Team Danto” were common. As we stood in discussion of the exhibition on view, he interrupted our conversations if they bordered on mere formalism or rote repetition of October, but only to say, curtly and matter-of-fact, “And? What else?” He would then leave us to our discussion, returning minutes later to ask us yet again, “And? What else?”

The comedy in this pedagogical routine was admittedly short-lived, but his simple query stuck with me. It encompasses a perennial difficulty, how to determine if what matters in the microcosm of art practice — the studio, the museum, the works themselves — has meaning in the architecture of the world-at-large. If it isn’t ultimately relevant outside that microcosm, then art practice ignores how it is but one type of image among the many we observe everyday floating across monitors, flashing on signs, and reflecting in the pools of one’s eyes.

Aaron Van Dyke‘s current exhibition at Bethel University, ”Photographs” and Paintings, consists of small-scale works that function as documents of the artist’s studio practice. Although, visually, these works look abstract, more accurately, they are best understood as manifestations of a certain set of material conditions that demonstrate the objecthood of painting and photography.

In this exhibition, Van Dyke’s ”mirror photos” defy the medium’s common function as merely imitative, as a document of the external world. This type of abstract photography in which Van Dyke takes part has experienced a recent resurgence — artists like Walead Beshty and Melanie Schiff come to mind — possibly as a stance against the slow disintegration of film photography and the physical photograph in the wake of digital media.

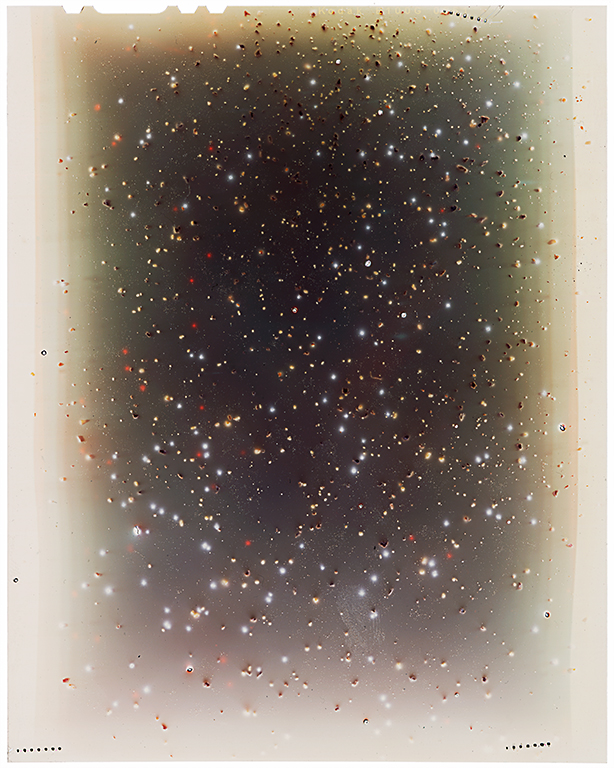

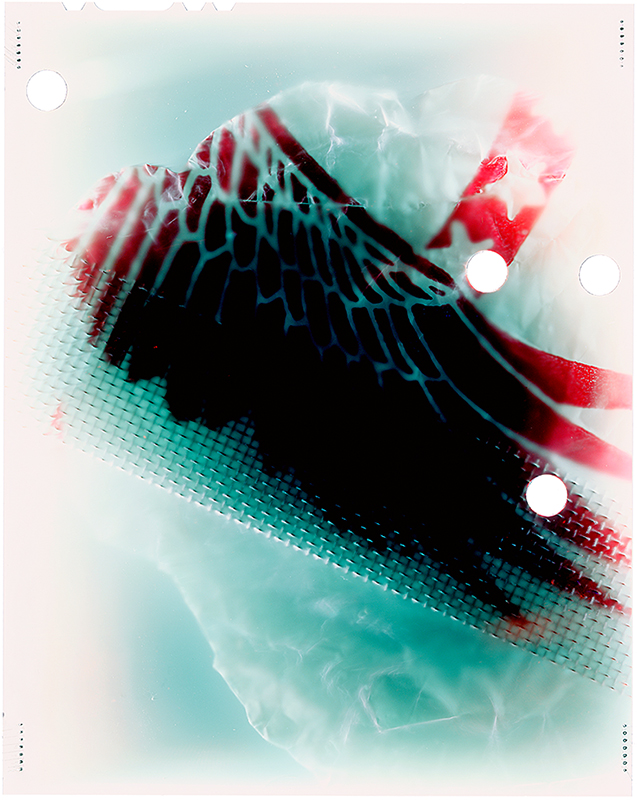

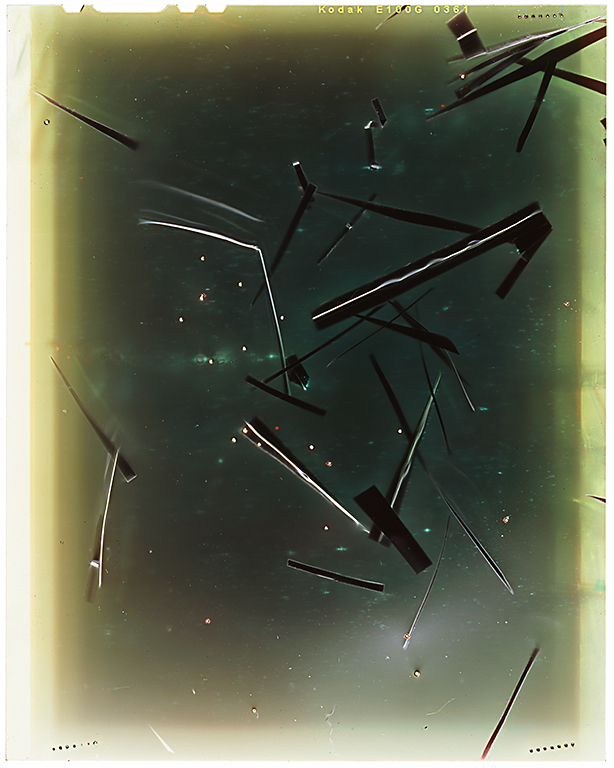

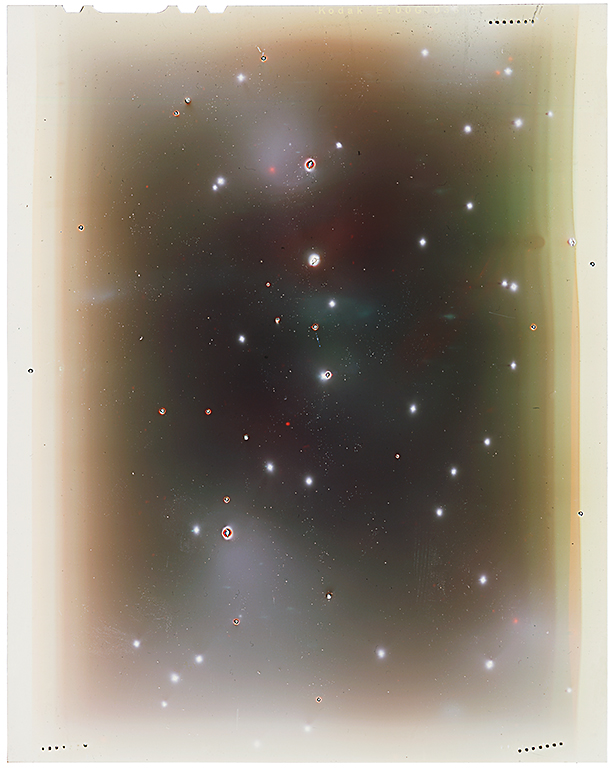

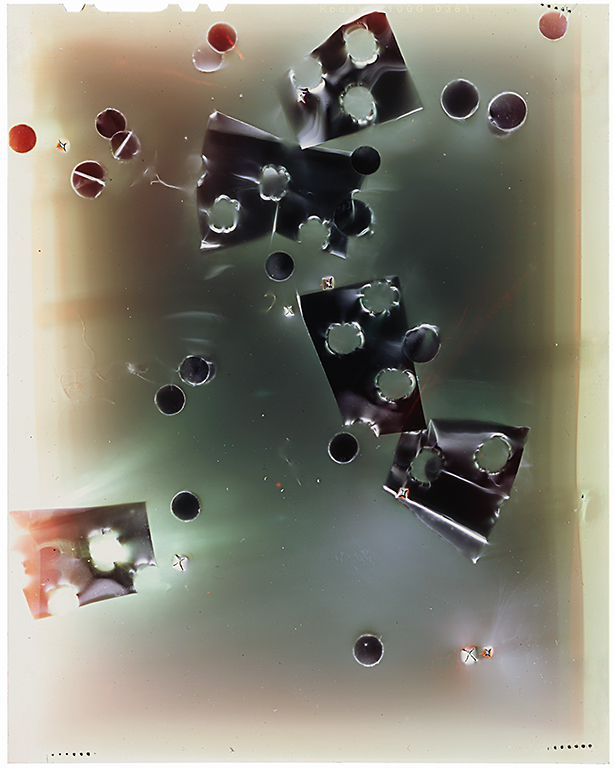

In the mirror photos, 4” x 5” inkjet prints, what appear to be images of debris float, as if suspended in a post-apocalyptic dust. The ephemeral appearance of these works belies the rigid program under which they were produced. These camera-less photographs, otherwise known as photograms, are based on an ur-photography principle that utilizes the simplest of means to achieve unexpected effects. In the case of Van Dyke’s works, these very basic materials include mirrors, light, photographic paper, the occasional bits of plastic, and dashes of salt that have been added to the paper’s surface. The process of creating these images is equally simple: Van Dyke takes two mirrors, places a sheet of photographic paper between them, and then exposes the paper to light.

______________________________________________________

The ephemeral appearance of these works belies the rigid program under which they were produced.

______________________________________________________

Beyond the photograms’ indexical traces of their making, on a conceptual level, they also reveal an experience of vision-as-failure. In principle, we all know how difficult it is to take a photo of a mirror. The mirror is an invisible medium, a mode to reflect visual information and ideally, without interpretation. But the fact is mirrors do lie and do tend to reveal themselves; just think of all the annoying amateur photos posted on Facebook, where the mirror’s presence is betrayed in the shot by a spark of light radiating from its surface. Van Dyke’s photograms also reveal this fiction, the promise of unmediated reflection, by turning the mirror on itself.

The most successful of his photograms are those like Untitled (N9), an image that gives the appearance of a dusty galaxy emanating from a shadowy cloud of destruction. Like Fontana’s holes and cuts that point to a space beyond the picture plane (a similarity aptly noted by Barholomew Ryan in his introductory essay for this exhibition), Untitled (N9) reiterates the two-dimensionality of its surface by the lack of perceivable depth between the floating debris (the figure) and the mirror itself (the ground). The visual immanence of the mirror is displaced, even usurped, by this quasi-alchemical process of creation, where out of relatively nothing these rudimentary photograms create new images.

Although Van Dyke describes his photograms as attempts to make ”the most unmediated images possible,” some of his works are, inevitably, more mediated than others. The artist’s insertion of material between the mirrored surfaces and his after-the-fact digital manipulation are examples of additional mediations. Actually, a number of these works appear ornately designed and quite heavily modified, as if they’ve been solarized too many times in Photoshop.

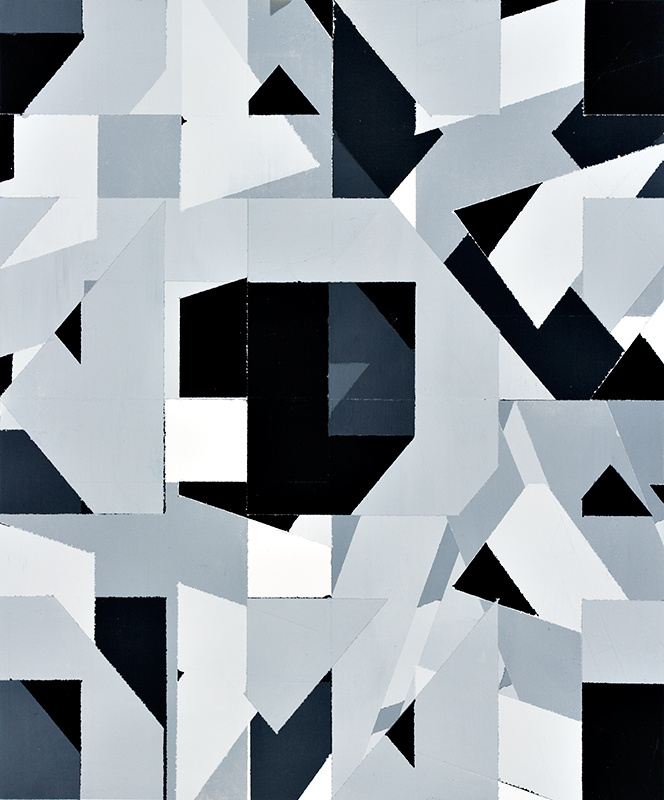

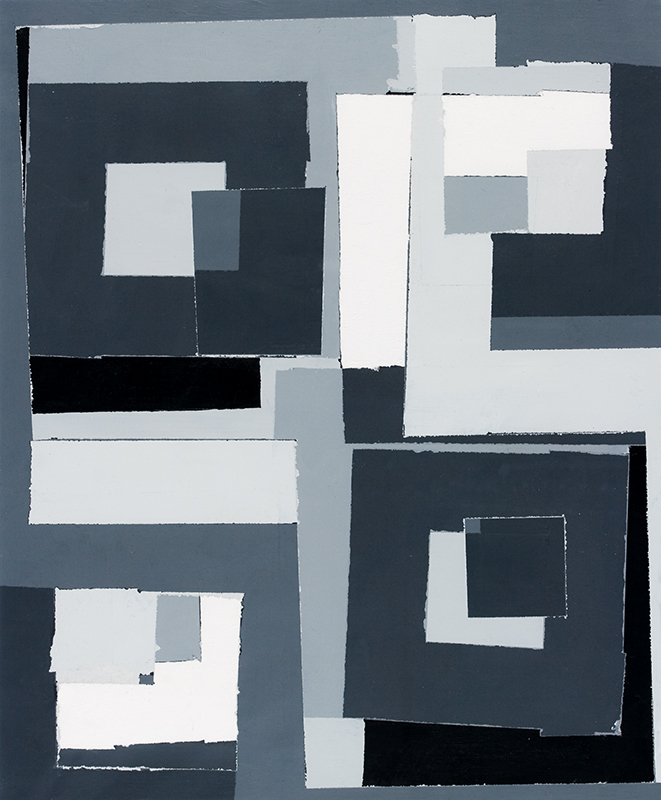

The paintings, all composed in a reduced color palette of black, white, and gray, follow a process of accumulation and revelation whereby Van Dyke builds up layers of tape upon the paper suface and then, intermittently, tears them away; he then applies paint to the sharply defined geometric areas. Van Dyke’s process appears to be an intuitive one, guided by partial blindness — blindness in the sense that Van Dyke, while he’s working, cannot see past all the layers of tape to the final product. Less conceptually compelling than the photograms, the kaleidescopic and architectural patterns that play across the paintings, like their photographic counterparts, remain almost resolutely two-dimensional. The blacks, grays, and whites do not delimit shadows, light, and depth as much as all-over, sprawling designs. This emphasis on two-dimensionality across visual formats is not specific to just Van Dyke; the prominence of image circulation on the Internet has flattened everything. Popular art blogs such as I Heart Photograph and Vvork use the blog format to exhibit a variety of artwork, but on a monitor, everything becomes tiny and flat.

In the end, Van Dyke’s works make incisive claims as documents that trace his studio explorations, whether into the materiality of photography or the process of painting. Past this line of formal inquiry, though, I can’t help but think what the next step could have been, the ”And what else?” element that would have taken this exhibition beyond a picture of the studio.

______________________________________________________

Noted exhibition:

Aaron Van Dyke: “Photographs” and Paintings is on view in Bethel University’s Olson Gallery through March 28.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Corinna Kirsch is a curator and writer currently living in Minneapolis. She received her MA in Modern Art History, Theory, and Criticism from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Motherwell Journal, …might be good, Proximity Magazine, and her forthcoming writing will appear in ART PAPERS.