Spice of Life: Variety in the Kinetic Kitchen

Lightsey Darst surveys a range of choreographers in their work for Kinetic Kitchen recently at the Mounds Theater and the Varsity.

introductionSometimes you want immersion: one choreographer, all night. Sometimes you want variety: several choreographers sharing a program. Kinetic Kitchen hits the latter spot. Sarah LaRose curates this showcase every month or so, usually at Mounds Theatre. Mounds is off the usual circuit but worth the trek for its charming Art Deco-inspired décor, kind staff, and Kinetic Kitchen itself, which serves just that meal of dance appetizers you have been promising yourself. This review covers two recent evenings of Kinetic Kitchen. The next Kinetic Kitchen (at Mounds Theatre) will be July 9.

______________________________________

Weight: sag: emptiness of moving from one place to another—but the pleasure, on the other hand, fulfillment of emptiness, that moment of knowing only that the body breathes and time runs forward. Sarah LaRose’s meditative “Comparatively Empty” shocks with its brave ambition: to contrast the undance of minimal gestures—a side-to-side swing viewed from the back, an arm flopping over—with Beethoven’s Moonlight Adagio, music we’ve come to think sublime. By finding holes between Beethoven’s heartbreaking notes for banal modern ache, LaRose at once elevates our littleness to quiet nobility and humanizes this high music, calling attention to the arduous steps of its structure.

Chris Schlichting joins LaRose in presenting quiet, almost undancing dance, though his “Waves 1 and 2” and “Person 1 and 2” are lighter in mood. In “Waves” Schlichting and Hannah Kramer (alternately impish and powerful, entirely alive, Kramer’s a wonderful find) begin in silence with wavelike hand gestures, which morph into slow-mo running as Jolie Holland’s country-western twangs over the sound system. In both dances, Schlichting moves dancers around the stage and in and out of unison with assurance; positions never look forced. Schlichting also excels at natural-looking, meaningful and yet not quite determined gestures. Neither piece quite rises to communication, and both feel long, but I’m excited by Schlichting’s ideas, talent, and skill.

Where Schlichting’s duets flow naturally, Gerry Girouard’s tangos jolt and grind from one physically stunning trick to another. Girouard imagines barely possible things and makes them happen—his partner, Kelly Radermacher, slides to a split, he pulls her from the floor and into another mid-air split, and they spin—but he doesn’t connect these moments. It can’t be easy: tango plays to an internal rather than a frontal audience, and Girouard’s favorite wall-climbing tricks don’t merge easily with partnered dance. Would this be more effective in the round? as a dance movie with some dislocating camera work? with a strobe light? Technical challenges aside, I preferred “Tango Volition” to “IN and OUT of Love”: in “IN and OUT of Love” inventive dance portrays emotions familiar from soap operas, but in “Tango Volition” dance itself is emotion.

In Laurie Van Wieren’s “Hypergraphia,” tango beats out not erotic tension but self-dramatization. Hypergraphia—the need to write constantly—afflicts the dancers as they scribble on clipboards, in the air, on the floor. As they scribble, they tango—— subtle and sleepy hip-shifts, sharp prancing steps, exacto-blade lunges—the tango, like the scribbling, an involuntary expression of the furious drama inside. Since we never know what the dancers are writing (even when a dancer chalks on the floor, it’s not legible), all we get are the flailing gestures (a dancer drops her pen on the floor, another leans over in an awkward, half-forgotten attitude) that accompany attempted self-revelation—just as much as we usually know about each other. (Since I first saw and commented on “Hypergraphia,” Van Wieren has added another dancer and more movement, allowing the audience into the piece.) Art, with its obsessive desire to create, remember, and recreate people, emotions, and ideas, must be kin to hypergraphia; by making art about hypergraphia, Van Wieren laughs at herself.

Tango’s in the air: Anja Gallagher-Syfrig has also breathed in a lungful. Gallagher-Syfrig creates the sexy contortions of a woman dancing before a mirror, and as she dances her own choreography, the steps disappear into her livewire energy. In Part I of her “Tango Calor,” Gallagher-Syfrig leaps high, makes time with her switching hips, and looks right at you; she’s a marvelous performer, fearless, comic, and sexy. Younger dancers performed Part II; I mistook one of them, Michelle Collins, for a dancer in Mary Harding’s “. . . is of the Essence” (performed at Best Feet Forward), because both these serious brown-haired young women have somehow grasped that dance is deeper than vanity. If they know this already, where will they be in ten years?

Behind Becky Heist’s “Open Throat, Inner Cells,” sheep-bells tinkle and country voices murmur. Her costume’s terra cotta and maroon velvet likewise invokes the element of origin, earth. But the earth itself, that element toward which Heist’s contracting body reaches, is absent, and without it, the piece feels unfinished.

Like Heist, Judith Howard is alone on stage in her “Waltz”—alone except for a stuffed gorilla, who becomes her quiet partner in a love drama. Howard spins on top of her gorilla lover, pushes him away, slides him down her body as if forcing herself out of his embrace, and drags him behind her; wrapped Roman-style in a white sheet, she maintains a noble attitude (exploiting her sculptural figure), except when she makes monkey faces in imitation of her lover. Even as I laughed I found myself moved by this little melodrama. Howard uncovers a gemlike story of self-delusion, manufactured love, and generous emotion, all in the plush body of a stuffed animal.

In a tai chi demonstration, Fred Marych lunges and shifts across stage, his rippling body nearly invisible inside a calligraphy of black silk, his hands describing some temple or quiet garden—then, in a single stroke, kills someone. Another minute of shimmering lines in the air (while a cheery fifties instrumental plays), then he stomps on the stage, the sound startlingly loud. When Marych brings out a long bladed staff and swings it around, he’s a reluctant butterfly-slayer. I don’t know about an hour, but for five minutes, tai chi’s riveting. Could tai chi become the next tango?

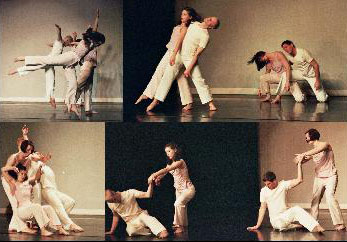

Christopher Watson Dance Company’s “Soft Landing,” a meditation on the way people pass in and out of each other’s lives, isn’t the next anything. With simple ballet-inspired modern steps (arms in fifth high as a repeated image) and sincere emotion, a piece like “Soft Landing” is as difficult to create now as a good seascape. CWDC succeeds because everything is well done: weight shifts in partnering without one dancer visibly leading another, the music (Sigur Ros) matches the mood and movement, each dancer’s path through the piece makes dramatic and visual sense, and the dance explores its material with truth, beauty, and hope. Sarah LaRose guides David Wick to a back corner of the stage, leading his arms into a high reach, then leaves him standing there, facing the back wall; Jodi Collova and Galen Treuer take turns lifting each other, exploring each lift as if for the first time, their feet vulnerable in the air; we do lift and leave, are left by, each other, and the parting does not have to be anyone’s fault. “Soft Landing” is also danced well, especially by Treuer and LaRose. Treuer’s open and natural as he moves from one sculptural line to the next. As her long body crumples or stretches, LaRose (both here and in her own “Comparatively Empty”) convinces you of the emotional truth of her dancing.