Real Positions: Self-Portraits by Seitu Ken Jones

The recent exhibition at Homewood Studios asks the viewer to become witness to complaint: to consider Black mortality and justice, masks and roots, history and perspective

Visual artist Seitu Jones brought me in to consult on a project that he and his wife, poet Soyini Guyton, are developing in the neighborhood we share in Saint Paul. Seitu was my art teacher, Peyton Scott Russell’s art teacher, and so I said yes to doing whatever I could for the project. That project, The Black Gate, will be an archive and studio-residency for African American artists. I spent five of eight years of graduate school (focused on literary and cultural history) holed up in the Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature, which is housed in the archives at University of Minnesota. I had also published a book with Minnesota Historical Society Press composed of archival materials. And so I had the idea that a book project about Seitu’s artistic life in this community might serve as a process for engaging others in helping to set the scope of the archive; also, the book might function as an invitation to a place in the cities where people could come together to make more books about Black Minnesotans. Minnesota Historical Society Press agreed to publish the book about Seitu sometime in early 2023.

The following exhibit review of REAL POSITIONS at Homewood Studios developed organically as a way to start setting some intentions related to the book, and just before the police killing of Amir Locke. I would like to dedicate it to the memory of Mr. Locke.

We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties. [...]

“We Wear the Mask,” Paul Laurence Dunbar (1895)

We see self-portraits of Seitu looking at us—defendant, plaintiff, and witness. Positioned below, above, and in between. Sometimes he lays dead.

Which is to say he’s been working in a particular mood since May of 2020. His initial reaction to the anti-Black policing spectacle and ritual was the early work (not part of the exhibition) Blues for George. George Floyd’s portrait in blue and black. Made of stencils and easy for others to carry into the public sphere. Repeatable like a tune. A people’s memorial to George Floyd, who would become an involuntary representative for a Black collective. His sacrifice would need to change the world…in order to save it.

Now Seitu—having spent so much of his energy outside and in the realm of public art—has returned to a gallery in North Minneapolis, where he was born. The small-scale exhibit of self-portraits is personal, but not useless to the rest of us. To my eyes, in taking responsibility for a problem that someone else created for him, Seitu’s mortality is the problem of Black (male) mortality in America. But to notice it requires that we match his grand gesture: we must willingly assume the position of witness to his complaint.

A simple triptych of unstretched canvases runs in primary colors from ceiling to floor. Life-sized ancestral figures gazing out to confront the viewer. No familiar exteriors for us to drift away to— instead, unworldly settings that demand confrontation with the figures. The gaze from the canvas is so stark and vacant, some might ask whether there is a hidden, private interior left for us to wonder about. Risking uncertainty, we confront the artist in three phases: antebellum, postbellum, and a suspended middle that eerily resembles the present.

In the red middle, his gaze pointed, hands up, possessing only the suggestion of a body in t-shirt and cargo pants and in stride. The body is an outline and container. All details, but those of the head and arms are somewhere else. The partial figure is suspended like a man having become an ancestor before his time. Leaving uncertain-us to sort out how to judge him: guilty or innocent? Demon or angel? Questions recited to an old tune, having become a metonymy of masks and hands that speak for souls spoken for by others.

Blue (postbellum) is on the left. The figure is anatomically incorrect. A modern sankofa bird looking back, neck broke (there are, afterall, parts of lynched figures in the gallery.) He’s turned away from us in three-quarter profile. His bag packed and guitar silent. Heading somewhere, looking back and broken. Hard shadows add something gothic, like the Puritan myth of Black evil which haunts the double consciousness blues.

Yellow is on the right. A slave standing in mute rags clutches his left hand with his right, as if he has a need to keep them busy. Antebellum fieldhand dressed for exposure to the sun, cold, and all things that bite. He has a body to protect. Skin alone won’t do.

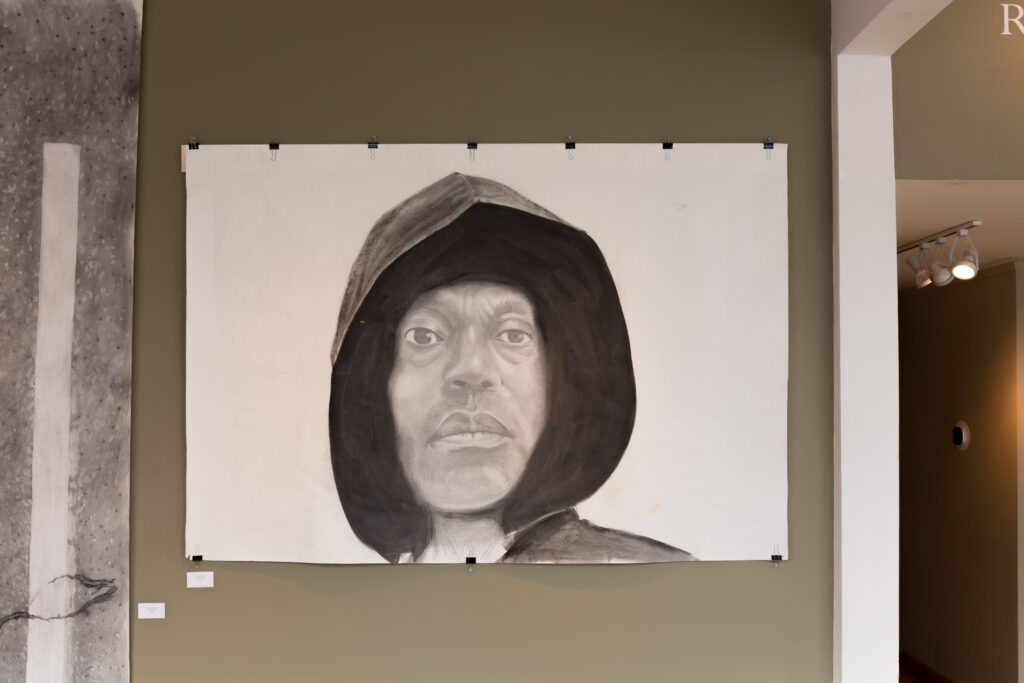

On another wall: a realistic, documentary close-up group shot in graphite at bird’s-eye view. A street scene drama capturing the ordinariness of the day, encapsulating everything we need to know about life. Figures cut off by the edge of the paper (only their parts visible) with Seitu lying prone, dead. A victim and the shoes of an anonymous bystander, witness and/or perpetrator who stands over the scene. A white line signaling the rules of the street takes up a disproportionate amount of visible space.And next to this piece is a graphite close-up of Seitu in a hoodie. Live and staring directly at the viewer like an icon. It’s a piece that I have seen before in his studio (like others on display), out of the context of the exhibit. Here, next to the street scene, it participates in the mythic drama that Black culture has rendered from George Zimmerman’s killing 17-year-old Trayvon Martin and which arrived at a climax, 12 days after the police killing of Breonna Taylor, in the murder of George Floyd and then Daunte Wright…

And, so, the artist bears witness to the new Jim Crow. One oil painting is simply a pair of eyes, rendered from a full palette of colors. What someone who once played with Buddhism and who, past 70 years old, can still sit full lotus might see as a “soft gaze,” rimmed in blue. The top of the strip of canvas misses the full brow, where an ambivalent audience might look to know how to know this Black man. At rest? Keeping cool? Deep in thought? Mad at the world? Or, is it—like the equanimous “Buddha smile” or the happy/sad twoness of the blues—all at once? It’s hard to know which, but he leaves more clues. Look—

From the point of view of standing beneath a tree, feet dangling in the foreground just below the top edge. Beauty in the distance, no other parts of the body visible. That’s the painting Strange Fruit. The bright, pastoral quality carries the irony and textured intoning heard in Billie Holiday’s famous ballad from 1939. Tone and image feed back on one another, reverberating still.

And there are other ironies on display: Spirit masks and COVID masks. Masks bearing the flags of modern African nations. The mask of identity as a balm to keep us healthy and alive. The masks that unite the African diaspora in rituals that generate the spirit, which helps us survive modern Blackness, doubles as the new ritual of isolating ourselves to keep from spreading infection and death.

Seitu Ken Jones, African Masks, 2020. Photo: Alexander Thomas.

Seitu Ken Jones, African Masks, 2020. Photo: Alexander Thomas.

Seitu Ken Jones, African Masks, 2020. Photo: Alexander Thomas.

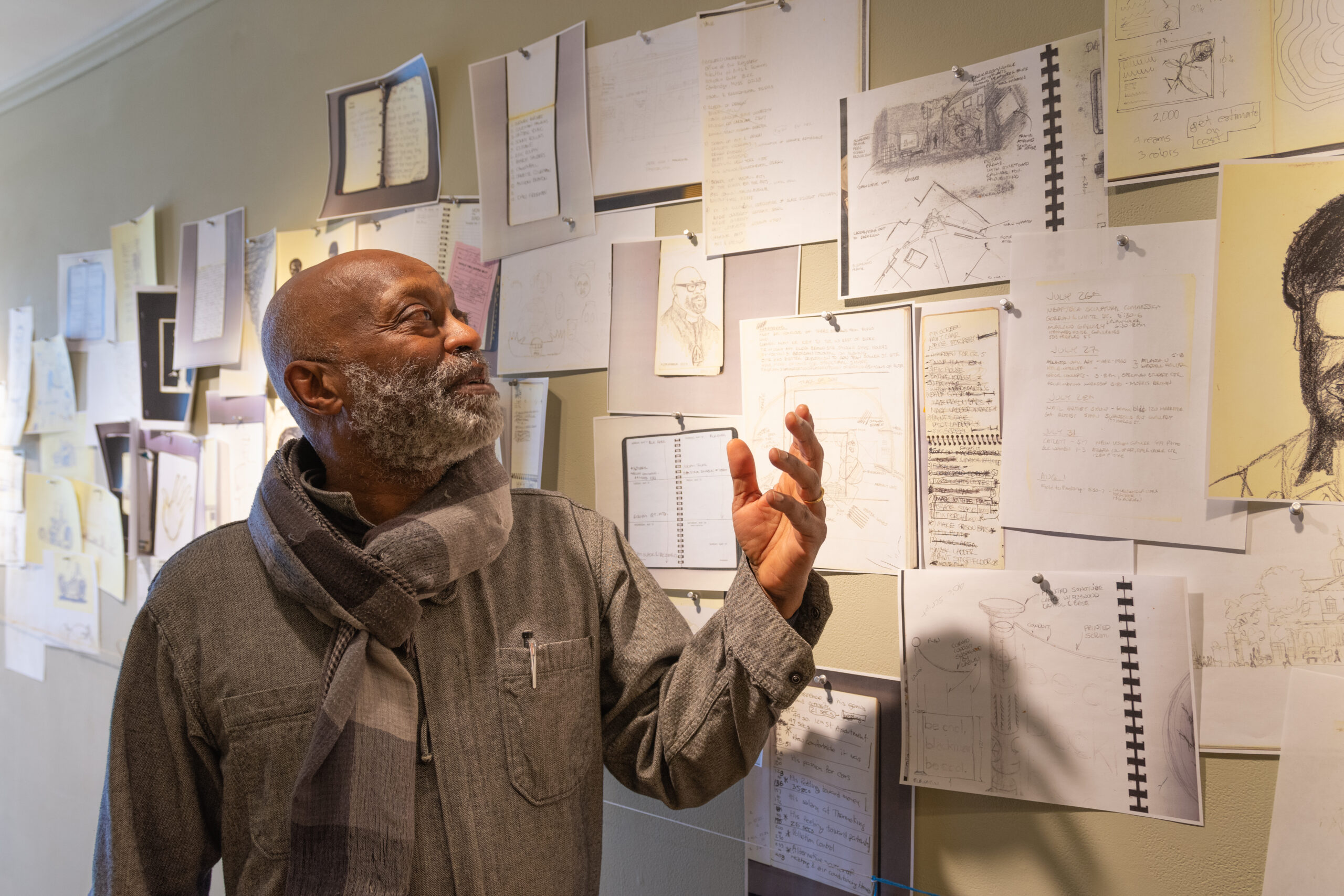

Thankfully, curator Neal Cuthbert thought to share evidence of the artist’s working life. As you make your way past the miniature COVID masks, you see copies from sketchbooks and daybooks along the wall, chronicling Seitu’s nearly 60 years as a working artist. You can gather a sense of his mind over the years, from a machine-obsessed innocent to Afro-blue skeptic. There’s a string made of various scraps that runs below the collage to suggest something about continuity. My 12-year-old son, August, stood next to me and said it reminded him of the plot line or network of associations that you see detectives draw between pieces of evidence as they try to solve a crime. Like Indra’s net and the process involved in one Black life bearing witness to another’s.

But there is a subtlety that runs through the exhibit, too (and, you might say, the present moment):

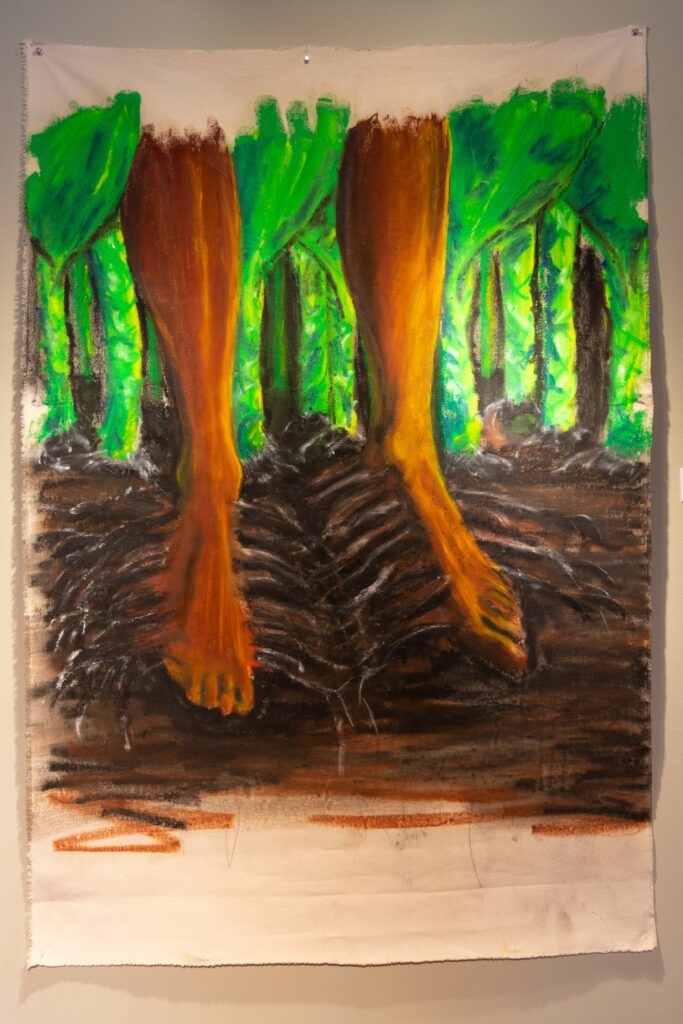

A remarkably sincere painting called Roots hangs at the end of a long hallway, as what seems like the show’s deeply buried hope. The companion to Roots might be the ironic Strange Fruit, but Seitu seems to have wanted to put some distance between them. The point of view is of a viewer standing (or laying) inches from the ground. The central image is a pair of feet that appear to be braided into cultivated earth. Brown ankles and legs emerge vertically and are supported in the background by bright green stalks, planted in careful rows.

Here Seitu elaborates on a theme introduced at the start of the show with the image of the itinerant bluesman of the Great Migration. Where movement once provided a tool of Black agency, in Roots, we have embodiment in place and land. There is no separation between body and earth as, in the painting, the two images run (pun intended) together toward a lesson: there’s hope in our position; hope that lies in what people who get to live long enough seem to always say. That thriving above ground depends on nurturing what’s below as you would nurture yourself. In gathering up our wholesomeness. And then—like a refrain—you are forced to walk back through the rest of the show, through the brokenness. You are required to remember.

REAL POSITIONS: Self-Portraits by Seitu Ken Jones was on view at Homewood Studios from January 4-29, 2022. More information at homewoodstudios.com.