Poems Born of Music

Poet Connie Wanek reviews the latest collection of poems by Todd Boss, PITCH, just released by W.W. Norton, likening the felicity of his language, lyricism and narrative richness to likes of e.e. cummings, Kay Ryan and Robert Frost.

“I…have consciously set myself to make music out of what I may call the sound of sense.”

Robert Frost

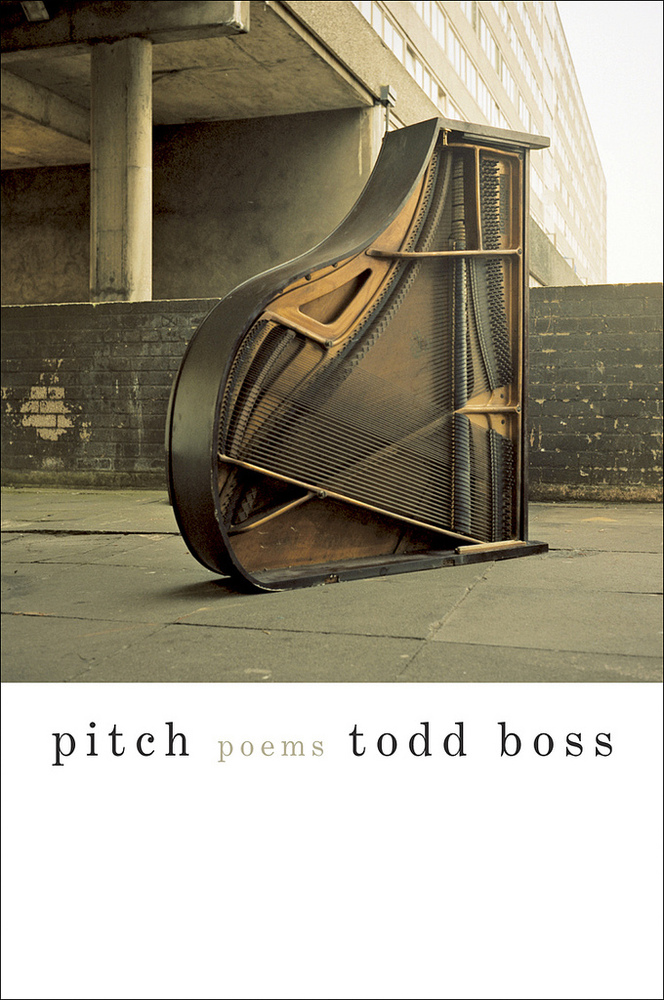

TODD BOSS‘S SECOND BOOK OF POEMS, Pitch, was released a few weeks ago by W.W. Norton, which also published his acclaimed first book, Yellowrocket, in late 2008. The striking jacket photograph for his new collection shows a legless grand piano on its side, revealing its soundboard, a disclosure of sorts: here is where music is born. A gritty urban setting surrounds the piano, an unpopulated concrete alley, which creates an atmosphere at odds with the narrative poem to which the photo clearly alludes: that is, the four part “Overtures on an Overturned Piano.” This is a rural poem, and it begins:

From farm to farm and one more midnight mile to go my father took too fast the last turn --on black ice-- and presto, over the side of our half- ton Ford and into the drainway went my father's father's brother's turn-of-the-century Steinway piano...

Like many of Robert Frost’s long narratives set in the country, this poem is very much a story about people — a marriage, a child, a father, uncle, grandfather, brother. Frostian, too, are its themes of striving and failure, family rivalries, unspoken passions, affections, and anger — the often dark, driving forces that are engines of literary power. “One more midnight mile to go” instantly recalls Frost’s most famous poem in which the narrator has miles to go before he sleeps. Syntactical inversions, such as “took too fast the last turn” (rather than the more conventional “took the last turn too fast”), also remind one of Frost’s opening lines: “Whose woods these are/ I think I know.”

It’s a marvelous literary heritage to claim, and an ambitious one. Todd Boss, like Frost, also prefers his tennis with a net, taking immense care with a poem’s rhythms and rhymes, and the arrangement of words on the page. Consider “Should Leash Laws”:

This poem ticks like a Roladex. Its physical appearance, scattered across and down the page, mimics the effervescent dog greetings it describes. It’s a good joke on people, too — with our “rules & regs” — even as the poem itself conforms to the dictates of its own internal structure. It ends with a happy witticism. It’s inventive, fun, even elegant, like the footwork of Fred Astaire.

Playful as it is, the poem also raises substantive questions: Why do people have so many rules? How do our parameters alternately focus and limit us? And what about rhyming poetry? Rhymes are a kind of rule, but a flexible rule (which is not an oxymoron) with varying degrees of obedience required. Perhaps we can think of rhyme more as a quality that some poems possess more strongly than others. If so, the poems in Pitch share this lyrical, rhyming quality to a remarkable degree. Very often we “hear” the poems clearly as we read them on the page — no need to say them aloud. The following are lines describing cello music from “It Isn’t All Fiddles”:

...The rough chew of horsehair trying to flow through wire. The bow of bale on woe. I know. I hear it too.

It is a fundamental pleasure, and a memorable one, to experience this much poetic lyricism, and it is probably the single quality that most of Todd Boss’s readers associate with his work. An obvious contemporary comparison would be to the poetry of former U.S. Poet Laureate, Kay Ryan. But such verbal felicity and sense of linguistic play also recall e e cummings, and have still older roots in the metaphysical wit of Andrew Marvell (consider “To His Coy Mistress” or “The Mower’s Song”) and other 17th century poets. The cross-pollination of poetry and song at which Boss excels, the difficulty of determining which art is in charge in a particular work, is as ancient as the troubadours.

Boss’s verbal felicity and sense of linguistic play recalls e e cummings, with still older roots in the metaphysical wit of Andrew Marvell and other 17th century poets. Indeed, the cross-pollination of poetry and song at which Boss excels, the difficulty of determining which art is in charge in a particular work, is as ancient as the troubadours.

In our era: how many have called Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, or Eminem, for that matter, poets? And why not? Try singing the words of “Stopping By the Woods on a Snowy Evening” to the tune of “Hernando’s Hideaway” (I may be dating myself here.) To say that the poems in Pitch tend toward music is to state the obvious. Consider the multiple meanings of the book’s title. Consider the collection’s table of contents: poems called “Three Funeral Songs” or “A Waltz for the Lovelorn.” There’s more than a little country twang in “Luckenbach,” just as there’s Bach and Bartok in “Overtures on an Overturned Piano.” In Pitch, one feels in the presence of both a soloist and a skilled composer.

Of course, it’s been pointed out many times that rhyme has its attractive dangers for the poet. Chief among them is the way what rhymes with what (putt? slut? haircut?) can alter the course of the poem. A reader may wonder, for example, whether that’s what happened in the impressively tidy “Amidwives: Two Portraits.” Here the notion of a wife “weaning” her husband from his mother’s milk (the “sweet taste” of it), and correspondingly, a mother wooing the “married man who/was once her darling/son,” trying to create conflict in the marriage — well, the implied incest/murder (the mother runs “a tempered blade/into the marriage/ bed”) is daring. But one might find the poem thematically anachronistic, the abrasion between wife and mother-in-law a too-familiar trope. But who can argue with the powerful sense of inevitability created by the cadences and rhymes? How to resist saying what the rhymes want to say!

The same approach, however, works very well in the excellent, democratic opening poem, presented here in full:

It Is Enough to Enter the templar halls of museums, for example, or the chambers of churches, and admire no more than the beauty there, or remember the graveness of stone, or whatever. You don't have to do any better. You don't have to understand the liturgy or know history to feel holy in a gallery or presbytery. It is enough to have come just so far. You need not be opened any more than does a door, standing ajar.

Perhaps rhymes are similar to musical chords; the words, like the notes, intimately correspond, and the sound they create together elicits unarguable human resonance. If so, there are minor as well as major chords in Pitch, and to return to Robert Frost, the sounds here make their own reality, their own sense. Boss’s new collection is divided into seven sections, each in its own key. It’s a deliberate book, carefully crafted, but one that also escapes captivity, and, like the dogs on leashes, it has exuberance, and is full of life.

Related links and information: Todd Boss’s new collection of poems, Pitch (W.W. Norton, February 2012), is available in bookstores everywhere.Find out more about the poet, his books, and other projects on his website: http://toddbosspoet.com/.