mnLIT presents: Alison Morse

Read Alison Morse's 2010 entry in the miniStories/mnLIT competition, "My Sister," selected as a finalist in last year's cycle by our full panel of flash fiction jurors: Alexander Chee, Daniel Handler, Heather McElhatton, Kevin Larimer, and Dennis Cass.

My Sister

When I was a boy, I watched my older sister skip the fourth year of school, then the fifth and sixth. All this, my quiet sister did, her brown eyes glazed from sitting up nights memorizing — in their original Russian — Pushkin, Lermontov, even Blok — not just our own Yiddish poets. I’d pass her room on the way to bed and see her black braids curtaining whatever book she was ingesting. I wanted to pull one of those black ropes, just to get her attention.

At eleven — only three years older than me — she wrote her first verse in Russian. Genius is what the teachers and my mother called my sister of the long black braids, ends likes pen nibs, skin as pale as pages. She wrote in a fever in our little hut in Vilna, by candlelight, her braids lying dangerously close to the dripping wax.

“Rivke, what are you doing?” I asked.

“I’m dancing.”

“It must be a very bad dance.”

She giggled and threw a balled-up piece of paper at me. Her laugh was a melody in B Minor.

Our father was already dead. One night, while fiddling the old song “Thou, Thou Thou,” his violin began to shake. Then he collapsed on top of me. I was seven, the family baby with arms too short to catch him. Within seconds, his white skin turned blue. I could no longer hear his breath.

My sister and I inherited Father’s white skin.

Sometime after her fourteenth birthday, Rivke began to turn purple: first her toes and fingertips then her arms and legs, as if ink had seeped underneath her skin. She lay in bed shivering, sweating, stiff, but did not complain; only said the candle flame was too bright.

One night, I woke up to loud thuds against the wall that separated my sister from me. It was the sound of her bed frame, banging against the wall while invisible hands gripped her entire body in a convulsive partner dance. “Brain fever,” is what my mother whispered to Aunt Dina. The doctor said “Meningitis.” My older sister swelled. She could no longer answer when I asked how she was — she had lost her ability to hear our world — but she did blow mysterious words in the air as if she were conversing with a boy I couldn’t see, a partner whose spasmodic lead she followed with the jerk of an arm or leg.

One summer morning, when I was alone with my sister, she looked at me and whispered something unintelligible. Then she turned into a ribbon of ink that flew out the window on a traveling breeze. I know this because I saw the word eternal purpled on the window above her bed.

As soon as this happened, I ran out to the bank of the Viliya River and wrote the word eternal in the sand.

My first poem; not my last.

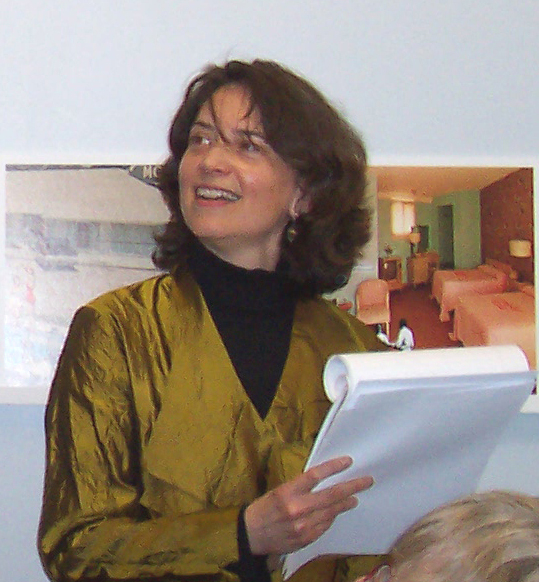

About the author: Alison Morse‘s poetry and prose have been published in Natural Bridge, Water~Stone, Rhino, Opium Magazine, The Potomac, and a bunch of other journals. She is currently spit-polishing a novel, The Beethoven Frieze, about animators during Yugoslavia’s collapse. For twenty years she animated everything from cigarettes and glass shards to Barbie doing aerobics on the beach in Cancun. Now she teaches and runs TalkingImageConnection, an organization that brings together writers, contemporary visual artists and new audiences.