Minnesota’s Third Biennial: The Art Stands Alone

Individual pieces may stand out, but the hands-off, artists-first approach of , , , ends up making the show largely inaccessible to the audience.

For The Soap Factory’s third Minnesota biennial, the largest gallery in the Twin Cities has solicited John Marks and David Petersen, the creative team behind the notorious Art of This gallery, which existed from 2005-2010 in south Minneapolis. Titled ‘, , ,’, the exhibition acts as a kind of anti-biennial, “without a title, without a theme, and without a destination other than the exhibition itself,” according to the Soap Factory’s website. Like many of the shows at Art of This, the artist-centric approach of ‘, , ,’ ends up being pretty inaccessible to the audience, though individual pieces may stand out on their own.

I discovered Art of This in the spring of 2010, a few months before it closed. While I often enjoyed the work shown there, I always felt out of place when I paid the gallery a visit, like I had intruded on some private party to which I hadn’t been invited. In creating a space that aimed to support artists, they lost sight of the audience in the process — what it means to create an accessible space that invites people not associated with the gallery or the artists also to feel welcome to join in the dialogue.

In contrast, the Soap Factory has a reputation of welcoming all comers — something exemplified by their annual Haunted Basement (going on now), which draws thousands of people each year who might not normally go to an art show. Often the Soap Factory’s exhibition openings also include interactive activities, further encouraging visitors to meaningfully engage the work on view. It’s a gallery space where, no matter how far out the art is, anyone can come in and feel comfortable to see and look and participate.

To set the ethos of Art of This against that of the Soap Factory is an unfair comparison, of course. A nonprofit organization with a much higher budget than Art of This had to work with, the Soap Factory also has a wide network of volunteers, so they can make sure there’s always someone to work the welcome desk, to staff open hours and can, in other ways, provide resources to reach out to people beyond the social network of the owners of the gallery and its exhibited artists.*

Still, this particular partnership makes for an interesting clash of pretension and openness – something particularly in evidence at the Soap Factory on opening night of ‘, , ,’. On the one hand, a huge number of people showed up, as is usual at the Soap’s events; there was live music and other performances — it felt like a party. On the other hand, there were no gallery notes on the wall to indicate the titles of the pieces and few entry points for visitors to engage with some of the more highly conceptual pieces if they didn’t know something about the artists beforehand.

Critiquing the art world is as old as the art world itself, and in the last 100 years alone there have been numerous movements (the Dada-ists being the prime example) which have aimed to tear down the ostentation and snobbery of “high art”. But the curators’ critique implicit in “, , ,” feels false. I chatted with my friend and fellow arts writer Gregory Scott; he called Petersen and Mark’s decision not to actually curate the show a cop-out, and I tend to agree with him. The fact is, this curatorial duo was given an opportunity to curate a biennial in the largest gallery in the Twin Cities, and even paid a modest stipend to do so. Simply to shrug and decide you’re not going to do it may be in keeping with the punk rock mindset of Art of This, but it also feels like a big “fuck you” to the audience.

This curatorial duo was given an opportunity to curate a biennial in the largest gallery in the Twin Cities, and even paid a modest stipend to do so. Simply to shrug and decide you’re not going to do it may be in keeping with the punk rock mindset of Art of This, but it also feels like a big “fuck you” to the audience.

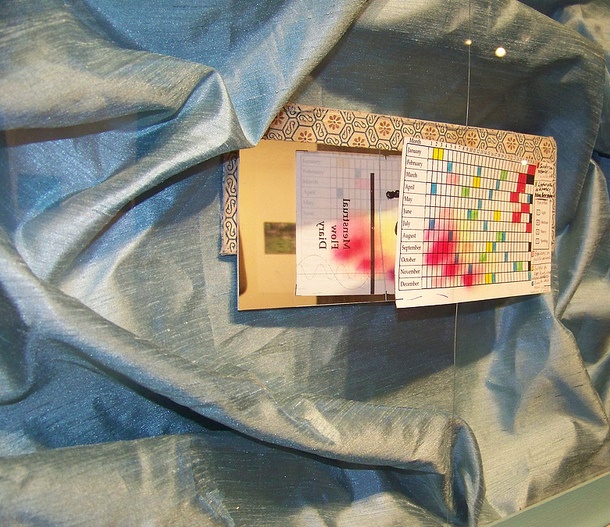

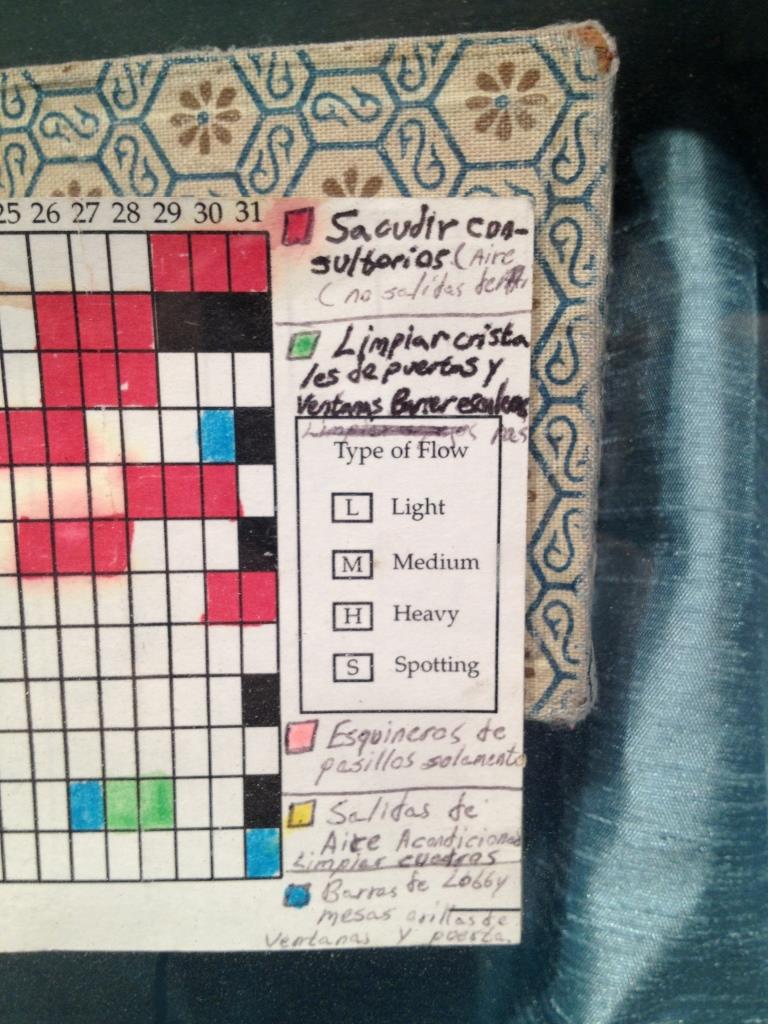

Despite my problems with exhibition as a whole, there are individual pieces that work on their own, despite the flawed structure of the show’s design. One of my favorite pieces is contributed by Michael Mott. Called Antique Love on Modern Equipment, the work is made from a found object, a menstrual diary used by cleaning staff working for Allina Health. The form had been appropriated and repurposed as a janitorial schedule, with color-coded notes in Spanish — presumably made by workers organizing their cleaning routines. The diary is attached on one edge to a mirror, so you can see the front side of the document as well as the back, where the Allina logo is visible in the reflection. The folded paper sits in a bed of blue fabric, tucked inside a box frame. The piece speaks to a glorious human resourcefulness and ingenuity.

I was less enthusiastic about another of Mott’s works, this one created with Adam Caillier: Negative Air Room. At first, I wasn’t even sure it was a piece included the show — the work looks like the sort of ad hoc structure one might find at a construction site. I found myself trying to walk behind it along with a group of older adults. “Is this art?” one of them said. Eventually we found the air-tight door and walked in. We met a young man waiting inside who informed us this was the “break room.” Indeed, later I returned to find people smoking in there. The stale smell of their cigarettes reminded me of an airport smoking lounge from back in the day.

In spite of my initial reservations, since attending the opening, I have to admit, Negative Air Room has grown on me. It may not be beautiful or even particularly arresting in the moment, but that room nonetheless provides an occasion for the audience: experience of the work prompts a dialogue about what constitutes “art” at the very least. The close quarters also mean you have to interact with the others in its space; active engagement with the piece is required just to find the entrance. Besides, any piece of art you’re still trying to figure out a week later has obviously made genuine impact. That fact alone is anything but negligible.

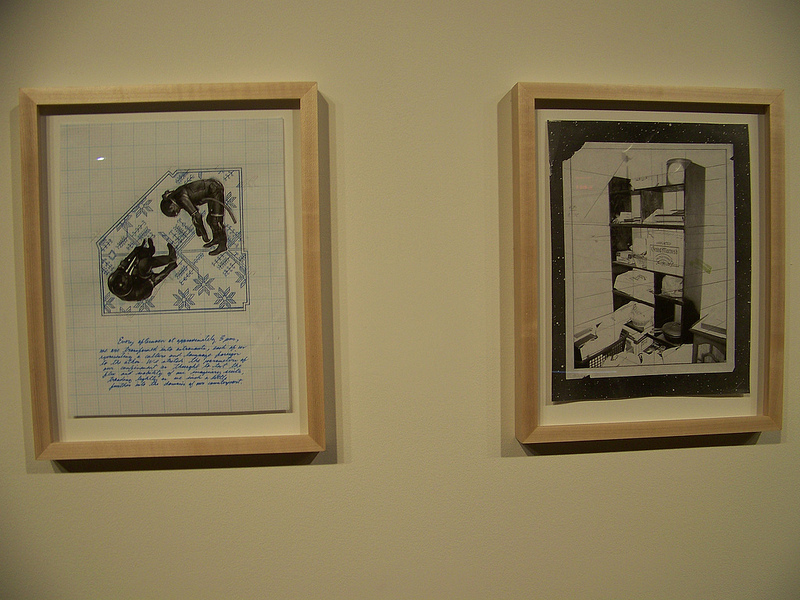

Natasha Pestich’s** For the Good of the Common(s): Images and Notes is also intriguing. Her series of drawings includes a lengthy introductory note that describes a public art project the purports to have been designed in 2010 by a group of students in Illinois, constructed as a house of cards. Unfortunately, the note explains, the structure collapsed, trapping the students inside for six days, and the project was never realized. Pestich’s contribution to the biennial offers several “artifacts” left over from the group’s public art project preparations, made on graph paper with pen and collage. The work is a sharp criticism of the current predicament of students taking on large sums of debt in order to study art. More broadly, it reflects on what it means to be both an artist and a human being in a community with others.

One scribbled note on one drawing offers a to-do list for one of the fictional participants if she is ever to “get out of here.” Among the notes: “Purge Facebook friend list. Consider anger management. Stockpile party favors.”

I liked the giant sculpture made of medical fabric used previously for an large-scale installation in Joshua Tree, California by RO/LU. Two pieces by Nate Young also bear mentioning: the first you see, close to the exhibition’s entrance, shows two pairs of hands rhythmically clapping on a video without sound; the second is a speaker, placed in a different gallery, that provides audio of the sound of the hands’ applause. Kristina Estell’s Outside is the New Inside is noteworthy too: a site-specific vignette of plants and construction materials gleaned from the gallery grounds.

Mary Abbe, of the Star Tribune, had some pretty unkind words about this iteration of the biennial, and especially for artist Broc Blegen. In her review, “Not Ready for Prime Time,” she writes of being drawn to Blegen’s piece for the show, at first. She was not amused to discover later that Allen Ruppersberg, Big Trouble is in fact a reproduction of a conceptual art piece by Allen Ruppersberg called Big Trouble — a piece Blegen reproduced (or rather, hired someone else to build) from scanned images.

I profiled Blegen last year for mnartists when he had his show in Minneapolis Institute of Arts’ MAEP Galleries. I’m a fan of his work. Here’s the gist: for the sake of building a private “collection,” he re-creates conceptual art pieces. The intention is not to copy for the sake of copying, but rather to make a political statement about the accessibility of art in a capitalistic society. Blegen’s practice springs from a desire to own works of art he admires but could never afford to buy. By replicating the pieces, he challenges the inequities of cultural access, questioning a money-driven system where the possibility of daily, intimate experience of great art is a luxury the 99-percent will simply never enjoy.

If you aren’t already familiar with something of the story behind Blegen’s body of work, there’s no way that you’ll be able to understand what he is trying to do. While there is a handout that provides maps of the galleries with basic caption information, I don’t see why there couldn’t be labels or other peripheral materials provided as needed — just a tiny bit of background, made readily available, to help visitors enter the work.

Related links and exhibition information: The third Minnesota Biennial, “, , ,” curated by John Marks and David Petersen, will be on exhibit at the Soap Factory through November 3, 2013. For more information and a calendar of related events, visit the Soap Factory website: http://www.soapfactory.org/index.php.

Participating Artists: Luke Aleckson, The Basketball Team, Broc Blegen, Allen Brewer and Pam Valfer, Adam Caillier, Kristina Estell, Katelyn Farstad, Emily Gastineau, Peter Happel Christian, Jess Hirsch, Andrew Mazorol and Tynan Kerr,Ben Moren and Daniel Dean, Michael Mott, Stefanie Motta, Scott Nedrelow,Jessica Ashley Nelson, Justin Newhall, Natasha Pestich, RO/LU, Andy Sturdevant,Nate Young

Participating Musicians: Jackie Beckey, Rachel Blomgren, Crystal Brinkman, Casey Deming, Isa Gagarin, Jonathan Kaiser, John Jerry, Nathan McLaughlin, Crystal Myslajek

*CORRECTIONS (Updated 10-22-13): While there is a small paid staff at the gallery, the Soap Factory’s volunteers, rather than paid personnel (as was indicated in the original version of this article), staff the welcome desk and serve as docents, when needed.

In addition, it’s worth noting there is an exhibition catalog and LP available for sale, with commissioned essays and excerpted interviews between the artists and curators for those interested in accessing all available materials. Gallery visitors may also submit responses to the show via the exhibition newspaper project, WOPOZI, coordinated by Sarah Burns and Oakley Tapola. The exhibition also included a number of performances and artist panels, led by participant Andy Sturdevant, throughout the show’s run. A full calendar is available here.

The original version made mention of Art of This’ “represented artists.” In fact, AOT was a nonprofit gallery whose exhibition calendar was determined by seasonal open calls for proposals. They didn’t “represent” artists as a commercial gallery might; they merely exhibited artists’ work.

**Natasha Pestich’s name was misspelled in the original version of this article. We regret the errors.