Art of the Steal

Sheila Regan considers two shows: recent unauthorized performances of famous choreographers' dance solos and Broc Blegen's conceptual art recreations, now at the MIA. She asks: Is this sort of appropriation plagiarism or homage? Fair use or naked theft?

No work of art exists alone, in a vacuum. Rather, an artwork is from the beginning part of an ongoing conversation, drawing from what’s been created around and before it. Many of the world’s great artists have gone even further, to blatant thievery: Shakespeare, for instance, borrowed many of his plots from other sources; Duchamp stuck a moustache on Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and called it his own. Indeed, 20th- and 21st-century contemporary art is full of examples of appropriation, from Andy Warhol’s famous soup can to Charles Mee’s (re)making project, which repurposes bits and pieces from classic and pop culture texts (“Euripides and Brecht… Soap Opera Digest and the evening news and the internet”) to create something new.

What’s more, pilfering others’ work has never been easier. Our current technological landscape creates an unprecedented level of access to copyrighted material. In particular, the internet — by way of a seemingly endless stream of blogs, YouTube videos, social networking sites, and search engines — gives individuals the opportunity to experience, often free of charge, a huge catalog of films, music, books, articles, and performances. As a result, battles have erupted over copyright issues surrounding use of artists’ works and how much (or whether) they should be paid for it. The issue is usually framed as a debate between those who advocate for artists (or for the managers/producers/publishers/labels who represent them) and those lobbying for unfettered freedom of information.

And these are precisely the questions several local artists, all Millenials, are raising in two recent shows: one, Broc Blegen’s Coming Out Party, is currently at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; the other is a dance performance from September, performed at the Ivy Building’s Studio 206 by Twin Cities dance artists Non Edwards, Erika Hansen, and Emily Gastineau. In both cases, the artists have gone beyond borrowing bits and pieces of existing work to recreating, in full, famous art works, and doing so without permission.

Edwards, Hansen and Gastineau created an evening of work featuring short solo dances by three pioneers of contemporary dance: Pina Bausch, Richard Bull, and Deborah Hay. Non Edwards performed So klag’ ich ihren Tod… from Orpheus and Eurydice, choreographed by Pina Bausch in 1975, originally performed by Dominique Mercy of Tanztheater. Emily Gastineau performed Exit, choreographed by Deborah Hay in 1995 and since staged by Hay and others in authorized performances. Finally, Erika Hansen performed Playback, an improvisational score by Richard Bull, originally danced by Peentz Dubble in 1984 at Warren Street Performance Loft in New York City. For her rendition, Hansen improvised from tapes created for her by George Russell, Meg Fry, and Kelly Donovan (all of whom were once members of Richard Bull’s company) and intended for her to hear for the first time at the performance. None of the original choreographers or their estates were contacted (both Bull and Bausch are dead; Hay is alive and still working). The Twin Cities dancers recreated these works based on their own readings of them and, with the exception of Hansen’s improvisation, not even former students or collaborators were contacted as they prepared for these unauthorized performances.

Similarly, Broc Blegen has for the last two years developed a personal collection of replicas of famous conceptual art works. For the show now on view in the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program galleries at the MIA, Blegen chose to show works from this collection of copies, as well as a selection of new pieces, that deal with the notion of “queerness.”

So, is this plagiarism? If you look behind these young artists’ reasons and into their methods, you’ll find the act of copying itself becomes a part of the art, transforming the “new” work into a statement about artistic practice, and about privilege. Their appropriation is brazen but, I’d argue, ultimately a curatorial act of homage rather than theft, a way of saying “these are the works of art important to me and that I want to share with others.”

Each of these young, emerging artists talks about how these projects have informed their own work and helped them to hone their craft. For instance, Non Edwards says much of the impetus for her recreation of Pina Bausch’s dance had to do with developing a form of practice to refine her skills. To that end, she decided to spend 100 hours learning the “stolen dance” as a way to delve deeply and intimately into Bausch’s solo. While dancers take classes, often on a daily basis, “there’s so little private practice in dance,” Edwards says. Musicians, on the other hand, even though they may be under the direction of a conductor or band leader when they perform publicly, regularly practice in their homes alone, for hours each day. While in school at Grinnell College, she remembers, she read how dancers, too, should spend an hour by themselves each day in the studio. She used her practice with Bausch’s solo to create a structure for herself in which she could accomplish that kind of private, daily routine.

Each of the dancers learned their pieces in different ways: Gastineau worked from a written score, Edwards from video; and Hansen practiced improvisation based on playback tapes by Richard Bull. With their unauthorized recreations of these works, the dancers wanted to find out what would happen if they practiced a solo long past the point of simply learning the steps, to what Gastineau calls “the excessiveness of working [the dance] again and again.” Ordinarily, rehearsal schedules are so tight, Edwards says, that they’re “usually sliding in under the finish line.”

And part of the motivation, they say, simply has to do with a desire to learn from the classics in their field. Musicians often master whole repertoires of music by the great composers. But how many dancers, Gastineau asks, have a Martha Graham or Isadora Duncan piece in their back pocket?

Similarly, Blegen was interested in getting inside the work he admired. Rather than being an intern for an artist, he says, he took on this project of copying work as a way to get to know the process behind their creation, and to get to know the pieces themselves. He says he wanted to figure out for himself the answer to the question, “Where does art happen?”

Blegen says he starts the process by looking for conceptual art that is “copyable.” Luckily, many conceptual artists don’t fabricate their own pieces, instead choosing to hire out the actual printing, etching, or other industrial processes involved in their making. So, Blegen selects pieces where the artist’s hand is less evident or even, in some cases, intentionally absent.

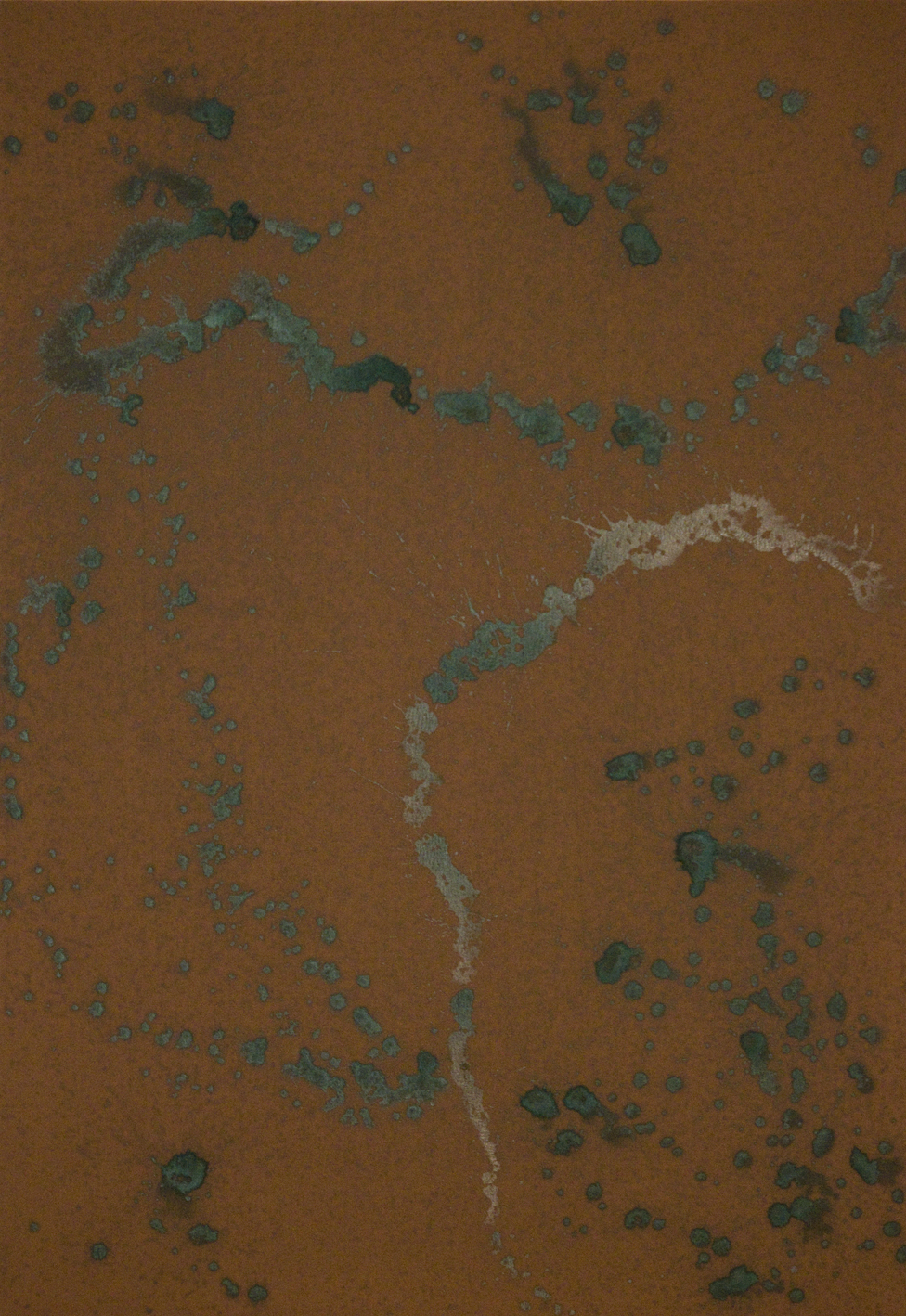

That said, Blegen recreated a version of Warhol’s Oxidation Paintings, arguably some of the least “copyable” and most varied and idiosyncratic of Warhol’s series. For the originals, Warhol mixed copper powder with acrylic matte medium until it was dense enough that it could be rolled on with a paint roller. He then had an assistant pee on the surface. Blegen says that, because Warhol didn’t actually do the peeing himself (usually it was Ronnie Cutrone), Blegen likewise delegated the peeing duty, to his father, who also helped him with some of the series’ construction. In his own versions of these collaboratively made pieces, Blegen always makes sure to credit the actual fabricators of the work– something that has never been a common practice in the art world, he says.

Blegen chose works for the current show that would “queer art historical narratives,” he says. In that sense, “it’s a political show that recognizes what is going on in Minnesota” with the marriage amendment and other culture wars that have surfaced during this election cycle. Blegen says he also wanted to push bounds of what’s usually found in the museum: “There’s very little [by] gay or queer artists in the [MIA’s] collection,” he says. “So, when I had this chance to do a show, I [decided to make the show] I’ve always wanted to see at the museum … [It’s my way of suggesting] that, hey, maybe we should accept proposals from local curators for [what’s shown in] the MAEP galleries, and to really push to create a new kind of space.”

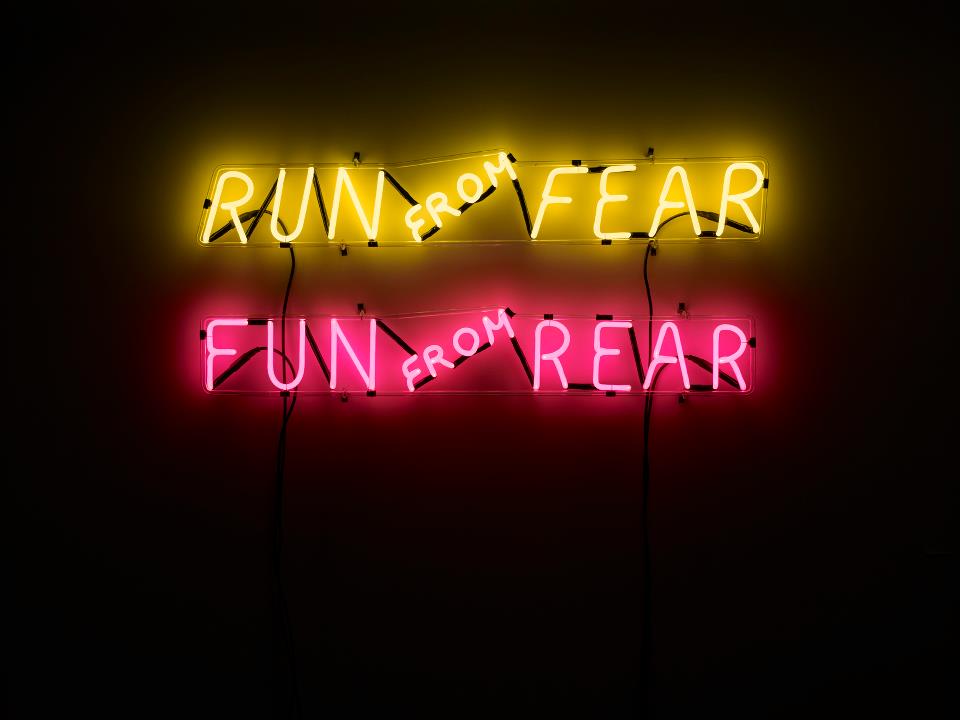

The emphasis on queering is evident everywhere in the exhibition. Blegen includes acopy of Jonathan Horowitz’s Crucifix for Two, which depicts two, connected crosses in a juxtaposition Christian and gay symbolism. There’s a version of Paul McCarthy’s Chair with butt plug — which is, as you’d expect, a wooden chair with a butt plug positioned in the center of the seat — and of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Go Go Dancing Platform), a light bulb-decorated platform, evocative at once of absence and presence, originally made by an artist whose lover died of A.I.D.S. Another powerful replication is that of Glen Ligon’s Red Portfolio a series of nine gelatin silver prints showing quotations of the Rev. Donald Wildmon, in hopes of starting a boycott of museum’s showing Robert Mapplethorpe’s work: “a photo of a man’s arm (up to the forearm) in another man’s rectum:” “a photo of a man urinating in another man’s mouth;” “a photo of a man in a suit exposing himself;” etc. Even Andy Warhol’s Oxidation Painting carries a subversive message about masculinity, Blegen remarks, perhaps poking fun at Jackson Pollock.

For all these artists, the process of recreating others’ works is an exercise in examining privilege — in terms of access to resources and instruction by the best in their chosen fields, but also more generally, the privilege of simply seeing and engaging with great works of art.

With regard to both the dancers’ unauthorized re-stagings of solos by Bausch, Bull and Hay and Blegen’s conceptual art copies, the process of recreating others’ artworks is an exercise in examining the privilege inherent in the pursuit of their chosen art form. For instance, a dancer might not have the resources or the right career trajectory to nab an apprenticeship at one of the world’s top dance companies; but, Non Edwards says, the endeavor to learn famous works gives any dancer a chance to “place herself in that lineage.”

There’s also privilege at play, not just for the artists making work but in access to great works of art. The original Richard Prince that Blegen copied for his show at the MIA sold for over a million dollars, as did the Warhol and Torres pieces represented in Blegen’s exhibit; the original works are now in the hands of wealthy collectors, and may never be sold again. Even if you can see the work in person, when you go to an exhibition, you only have, say, two months to see the piece, he says. But collectors know what it is like to live with a piece, to “see it in the morning, to see it when you’re drunk.” Blegen says he knew there were certain pieces that he wanted to know that intimately. He wanted to see what it was like to be around these works in relation to his own body at full scale. But the fact is, he says, even if these works were to come up for sale again, “I’m never going to afford them. [My choice is] either accepting that, or buying a poster.” Creating a replica, he says, exists somewhere between those options, though he notes, “it’ll never be real thing.”

When he first envisioned the collection, Blegen imagined it would be something private, made for himself only; but at a certain point that changed. “By putting it in a museum, I’m sharing what I’m doing and letting people do [something similar] themselves,” he says. “I love the idea that it could start a chain reaction, that I might start a seed of rogue collectors who may copy the pieces themselves.” Dancer Non Edwards, too, says she hopes other dancers will be inspired by her efforts to learn the work of other great choreographers on their own.

Blegen doesn’t intend to screw over the original artists. “The pieces have already been sold,” he says. “The only person I might be screwing over is the collector. The artist only makes money from the original sale.” And usually collectors make far more in the deal than an artist, he says.

Things work a bit differently for dance: A living artist — or if deceased, the artist’s estate — collects copyright fees for every production that features their work. Gastineau, Edwards, and Hansen all agree that for large companies, it’s reasonable for them to be expected to pay those royalties. They argue, however, that their project was so small, they’d never be able to afford royalty fees; but while they didn’t pay for the right to reproduce the work, they also didn’t profit by it: the dancers didn’t charge admission and they collected no donations for the production, they say.

The three dancers’ and Blegen’s shared status as young, emerging, minimally-paid artists should factor into the equation here, too. A year ago, Beyónce got into hot water about “stealing” dance moves from choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Interviewed by The Guardian, Keersmaeker said: “What’s rude is that they don’t even bother about hiding it. They seem to think they could do it because it’s a famous work … Am I honoured? Look I’ve seen local school kids doing this. That’s a lot more beautiful.” The fact is, Gastineau, Edwards, and Hansen went even further than Beyónce, admitting outright both from whom they were “stealing” and that they were performing the work without the artists’ permission or knowledge. Even so, under the circumstances Gastineau says, “I don’t think we were taking money away.”

Since Blegen began his collection of replicated artwork, he has reached out to two of the artists whose pieces he has copied. One of them, he told in advance about his plans to replicate some work.; the artist congratulated him on the idea, but declined to give him specifics about how the piece was made. The second artist Blegen reached out to but didn’t mention he was aiming to copy some work; that artist happily (albeit unwittingly) gave him specifics. about how the original was made.

For their part, the dancers argue they didn’t want to ask permission because “we were not dealing with the way the choreographers as people related to their work, and their personal feelings about how it should circulate in the world,” Gastineau says.

She goes on: “We were dealing with the texts themselves, the remnants that the artists left behind. Because the dance often lives in the body of its creator, we sometimes have a harder time separating the artist from the work (and maybe the artists have a harder time separating themselves). Our project was not interested in the artist as a person as much as in the work and its context.”

The restrictions of copyright law contain a pretty big loophole, “fair use,” which allows people to use copyrighted material within a new context. But what actually constitutes “fair use” is debatable; industry standards have often looked to the length of the copied material — how many seconds of proprietary video footage can be shown for a news story, for example. Another way to determine fair use involves consideration of whether and to what degree the original material has been transformed in the process of its reproduction.

When you look at the all work in question here, each meets that standard, at least to a point. Hansen’s piece, by nature improvisational, was probably the most transformed from its original. Gastineau, in working solely from Deborah Hay’s written score for the dance, also inevitably changed the work substantially in the process of interpreting it from those written notes. Even Edwards, who based her work from performance captured on video tapes, meets the “fair use” standard, by virtue of the fact that her reproduction is situated in the context of a performance expressly intended to offer criticism about privilege, practice, and the act of artistic theft. Even Blegen’s reproductions — intended to be indistinguishable from the original works on which they’re modeled — are not just replications, but also critiques of the art world at large.

All of them – Blegen, Edwards, Gastineau, and Hansen — are, in their copying of notable artists’ works, commenting on the privilege that hinders the development of young artists, as well as the problems of access. Perhaps most subversive at all is the fact that each of these young artists doesn’t wait for permission, instead taking the reins of curatorial power for themselves, declaring their right to question both the content and context of “great art.”

Noted shows and related links: Broc Blegen’s Coming Out Party is currently in the Minnesota Artists Exhibition (MAEP) galleries at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The show will be on view there through December 30, 2012.

Bausch, Bull, Edwards, Gastineau, Hansen, and Hay – Non Edwards, Emily Gastineau, and Erika Hansen gave unauthorized performances of solo dances by Pina Bausch, Deborah Hay, and Richard Bull on September 13, 14, and 15 in Studio 206 of the Ivy Building for the Arts in Minneapolis.