Jim Denomie: Finding the New Country in the Old

Lightsey Darst went to see Jim Denomie in his studio, to talk to him about his work. He's pursuing a new direction in his paintings and a whole new body of work has resulted--but it's one that feeds back into the work he's always done.

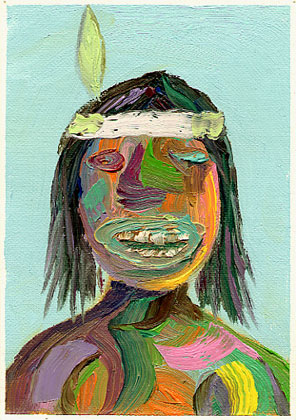

Every day since the beginning of the new year, Jim Denomie has painted a face. It’’s the same face, more or less: a Native person— sometimes a woman with two sets of concentric circles for breasts, more often a man with a headband and feather—with an open, toothy mouth, facing straight ahead. He calls them “Rugged Indians”; Denomie is Ojibwe. The faces are not large (5 by 7 or 8 by 10), and Denomie covers the surface area with wide strokes in bright colors, finishing in fifteen or thirty minutes.

After painting a face, he might work on other projects, paint another face, or simply go to bed, but every day he makes himself paint at least one of these small canvases. He does not try to create a perfect work of art; instead he lets himself play with the paint. He uses the colors already on the palette or adds new ones based on his mood. Daily surges of emotion affect the work, sometimes directly—one day’s face is grinning, another sour, one yelling (after the Red Lake shooting)— but more often indirectly: the faces evolve their own personalities, their own neutral but suggestive expressions, so that looking at many of the faces at once is like staring into a crowd of strangers. Denomie’’s not dogmatic about what goes into a face; some of the more abstract faces lack eyes and might not be recognizable as faces but for their company. When the face is done, Denomie signs the back and names it, if it happens to have reminded him of anyone.

Why is Denomie doing this daily painting project? Speaking on his cell phone from his full-time construction job, Denomie tells me he began the project because he found painting too often pushed to the side. Between work, family, and the rest of a normal life, he wasn’t getting time to go to his studio every day; when he did paint, sometimes after a week away, he felt “like a foreigner” in his own work. He was getting out of the habit and wanted back in. Inspired by other artists, Denomie bought supplies, told friends about his idea so he wouldn’t back down, and began.

Now, halfway through his project, Denomie’’s thrilled by his discoveries—all accidental, all not possible without the daily painting. He tells the story of one particularly difficult day when he thought he might not go out to the studio at all. Instead he decided to go out, take whatever color was on the palette, and just paint a circle with three lines through it. The resulting face—abstract, essential—so excited him that he stayed to paint another.

For a while, to save time, he worked in white and brown; when he brought color back in, he used a wider range than before—muddy half-tones, teals, strange marbled mixes of cream and violet. Because these paintings are finished in one sitting, he’s working with different effects—wet paint on wet paint, cleaning the brush on the painting itself—than in other, more carefully constructed pieces. As the project goes on, he finds the faces becoming more raw, more askew, more independent of him. He works toward balance between deliberation—since the painting time is brief, each stroke is important, as in “a chess game”—and impulse—intuitively tracing the desire that arises between himself, the paint, and the canvas. Simply, Denomie has proven that old saying about practice making you luckier; or as he puts it, the project has let him get his “head into the oven” of creativity.

This kind of daily art isn’’t new. Many painters, naturalists, poets, and other artists have completed such projects, with similarly invigorating results. Even Denomie’’s visual subject isn’t distinctive—the English painter Chris Ofili, who is black, paints a daily series of imaginary portraits in watercolors that he calls “Afro Muses”. What is surprising, though, is what this project reveals about Denomie’’s art and his ability.

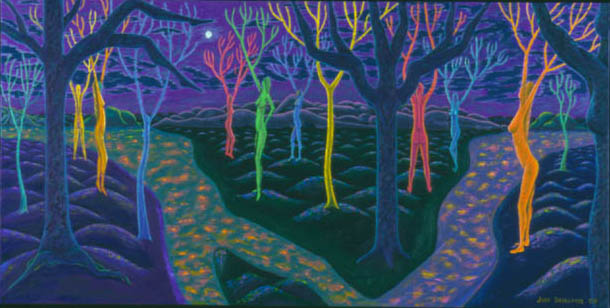

Look at Denomie’’s other work and you’ll find yourself fixating on the details as much as on the overall painting. For example, Dream Rabbit 5 is endlessly readable, almost profligate in symbols. You see the rabbit (the self, the artist, you), the skulls on the opposite pedestal (which may belong to antlered deer but resemble the long-eared rabbit), the interaction between the rabbit and skulls (as if the novice-artist had come to talk to the bones of his ancestors), the female bodies twining into trees and the mushrooms emerging from the ground (the background of men and women in their confusing maleness and femaleness?), and then the long female body in the rocks (a sleeping creative spirit, a distant mother, the mystic productive force). It’s night and everything is sleeping, save the rabbit, who is dreaming; the self moving through an alien world? the dark of the unconscious? or a veil fallen over the open life? In Denomie’s Renegade series, details tell a political story—slot machines, falling dollar bills, a white man on a broomstick pursuing a Native man on a winged horse, a “surplus cheese” truck.

The daily paintings, though, show no pictorial details (unless you count the feather or the uneven teeth), yet still display the same readable quality. Stare at several of them and your eye will be caught first by this one’s twisted mouth, then by another’s purple-daubed eye, the bleeding of cream into teal around another’s hair, disconnected magenta strokes across another—details of the medium, of the actual painting, that seem not to suggest personality but to tell you something real about the man or woman, about the moment, the story. I’m reminded of nineteenth-century images of representatives from different tribes, in which details of dress reveal culture and the collected images function almost as a field guide to Native Americans; Denomie’’s field guide, though, tells you about individuals, their moods, their abilities, how they’ve reacted to and been shaped by their environment—even though Denomie’’s subjects are imaginary.

Allegorical or story-telling paintings like Denomie’’s often get slighted in academic discourse. Allegory means that you’re more interested in telling a story than you are in making art, story-telling turns the medium into a mere tool, both belong to folk painting rather than real art, etc. That may be changing. If it is, Denomie’s “Rugged Indians” could be on the crest of a wave. In Denomie’s other work he employs vibrant color and loose, impressionistic brushstrokes, but in the daily paintings Denomie makes color and brushstrokes themselves the details of his story. These paintings are no less political for being abstract, no less concerned with medium for their narrative freight.

Not all of the daily paintings are equally successful. That’s part of Denomie’s “chess game”: he has ten or twenty minutes to make what he can. But he has discovered an ability that will move the rest of his art forward.

Once you’’ve talked to Denomie or seen his faces, you become tempted to start your own daily project. If you’re not a visual artist, though, figuring out a process may be half the struggle. Denomie’s daily works are rapid, complete, repetitive, and, in the process, almost pure medium; how can a writer, for example, replicate this? I began a daily poem project after my first conversation with Denomie, but although I can draft a poem quickly, I can’t finish one in a day or even a month. Limiting length and subject matter helps; still, given the irascible meaningfulness of words, I can’t do anything so free as squeezing a blob of phthalo blue onto a palette. A dancer or musician, whose art often interprets existing work, may be even more at a loss. I’m tempted to shortcut the problem and say that, regardless of our usual medium, we should all paint.

I went to Denomie’’s studio in Shafer to see the daily paintings, but I ended up staying much longer than I had expected as Denomie pulled out one project— photographic collage, monotype, painting, sketch— after another. We even went into his basement to look at some paintings that had been in boxes since their last exhibition. He’s not putting past work away as if it had nothing to do with him; instead, he’s returning to old symbols, reopening unfinished ideas, cherishing strengths, and improving on weaknesses. Possibly the greatest effect of the daily project is his new insight and renewed interest in past work. From feeling like a foreigner in his own studio, Jim Denomie has moved to a place where no part of his artistic life is strange to him. It’s all his country.