Is Red Wing the Artspot that Could, Or Will It Give Artists the Boot?

Writer Sari Gordon reports from the bucolic environs of Red Wing. As the area's arts scene takes off, residents find themselves at a crossroads: how important are artists to the health of the region's towns, and what are they willing to do about it?

FIVE YEARS AGO I QUIT MY HIGH-PAYING CORPORATE JOB in Eden Prairie and moved to Ellsworth, Wisconsin, to write a book. I wrote and wrote and spent up my 401(k) and wrote some more. And then I sold some stuff on eBay and kept writing—until a squirrel moved into the ceiling over our bedroom and I stopped writing and started sitting outside with a .22.

Today, I’m broke, I have a manuscript somewhere on a hard drive, and the land around me is squirrel-free. It’s not all it’s cracked up to be.

Red Wing is the nearest big town. I went looking for other writers, musicians, and artists to hang out with. It took awhile. If you walk around downtown Red Wing, you get the feeling that the cool part of town is right around the corner. While Red Wing has great arts institutions, the artists themselves are hard to find. In fact, I’d lived here three years before I found my pal David Culver, the amazing sculptor, living right down the road from me in Bay City, Wisconsin.

There should be a community. About twenty years ago, a tide of money washed over Red Wing. NSP built a nuclear power plant and paid the local Prairie Island Indian Community $2.25 million a year to store nuclear waste. Then the Treasure Island Casino opened, and is now the area’s biggest employer. Between 1978 and 1990, at least six major sites were rehabbed: The St. James Hotel (and $8 million investment), the Red Wing Pottery Place project, the Red Wing Armory, the T.B. Sheldon Theatre, the Riverfront Development Centre and the Red Wing Depot Renovation. Robert Hedin and his wife purchased the Anderson Center grounds and building outright from the Red Wing School District during that period and developed it privately. Down the road is a three-story barn with a poem on the side. Inside is one of the world’s last harp makers, a global music instrument store, and performance space.

_________________________________________________

If you walk around downtown Red Wing, you get the feeling that the cool part of town is right around the corner.

_________________________________________________

Today, Red Wing is faced with a challenge. According to a 2007 Comprehensive Plan, “[Red Wing] contains no major advantages relating to institutions, infrastructures, labor, incentives, and other such issues: quality of life comprises its primary attraction for businesses, residents, etc.” The report repeatedly states: “The City should promote other complementary businesses and organizations engaging in visual arts (galleries), music/entertainment, artisan-related uses arts-related development incentives.”

Robert Hedin, the Executive Director of the Anderson Center for Interdisciplinary Arts told me that in the last fifteen years of urban renewal, the arts have undergone “nothing less than a Renaissance.” The 52-year-old Red Wing Arts Association is at the center of the rebirth. Its gallery and shop sit prettily in the old Amtrak station in the center of the riverfront district. Right now they are featuring a statewide watercolor collective’s work, and each year they host a live plein air competition. There are only 250 RWAA members, but they raise a $120,000 annual budget and host perhaps the most popular Red Wing event, the Fall Arts Festival. The outdoor festival brings over 15,000 visitors to the area annually, and this year’s October 11-12 event was packed.

One of Red Wing’s most recent arts pioneers are John and Val Becker, proprietors of the Red Wing Framing Gallery. They moved to Red Wing from Minneapolis after 9/11, leaving their careers behind to follow a shared passion for art. Since then, they have hosted some remarkable and innovative shows: In 2005, they invited Max Becherer, a New York Times photographer working in Baghdad, to show his war photography. The wartime images were made all the more intense, framed as they were by Red Wing’s old buildings and hanging flower baskets. Last year, the gallery featured the extensive vintage pin-up art collection of Grapefruit Moon Gallery. Just last week, they opened a show of never-before-displayed original illustrations from the early 20th-century Cream of Wheat ad campaign. In the last two years, the gallery has attracted both local and national media attention.

_________________________________________________

The buildings of the Anderson Center look a lot like the correctional facility, the other big institution across town: solid red brick, wide lawns, and good fences. Sylvia Plath would have found them both alluring.

_________________________________________________

But even with all these shiny new arts venues, the contrarian brat in me scoffed at them all. My knee jerk reaction to the Anderson Center was, That’s the place for workshop writers who win grants. Real writers don’t apply for grants, they smoke and drink and, sometimes, write books. But after five years of book-free smoking, I deigned to make the ten-minute drive to the Center. The buildings look a lot like the correctional facility, the other big institution across town: solid red brick, wide lawns, and good fences. Sylvia Plath would have found them both alluring.

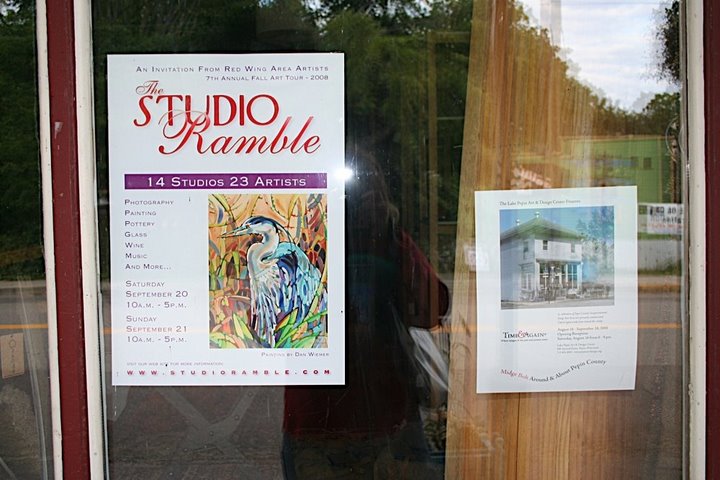

I happened to visit during the annual Studio Ramble, so there was steady stream of people walking between the numerous outdoor installations and the 16 artists’ studios on the grounds. I passed a pond where turtles sunned themselves next to a tiny green-hued cast frog and miniature turtle. I ached to sit in the glass-enclosed solarium and screened sunroom. That tranquil afternoon at the Anderson Center reminded me of nothing so much as a time, several years ago, when I visited an open air, 15th century courtyard in Fez, Morocco, where I lounged on carpeting and listened to hours-long performances of East Indian devotional chants.

Over my head a squirrel squealed at me then slipped like a snake down the side of a tree. He froze and, in a fit of bravery, hissed at me again and then darted away across the grass. These squirrels are red with white bellies and they clutched little clusters of oak leaves in their tiny paws.

After that I felt like writing.

A Place to Keep Your Nuts

John Kerwin darts among the rubble and ruin of the old Maltery Building in downtown Red Wing, anxious to show me what he has seen. The historic industrial warehouse is still outfitted for barley processing—the floors are actually perforated steel sections where the grain was left to drain, and nearby there are huge concrete casks. Kerwin first jokes that they’re the site of future SCUBA training classes; it turns out, he’s actually got plans for them to become circular galleries. The Maltery has only been empty for ten years, but a decade of emptiness has been hard on the structure. It looks like the workers went home just before an earthquake hit the three-story, 100-year-old building. (All these buildings downtown are 100 years old—what kind of boom happened in 1905, and how can we make it happen again?) At this point, the job of turning these gargantuan spaces into lofts looks impossible to my eye, but that’s precisely what Kerwin, an engineer, envisions. And he’s done it before.

Kerwin says he learned how to transform buildings from the late photographer Gus Gustafson in the early ’80s, when he bought and rehabbed the Milton Building in Lowertown St. Paul. From there, he moved on to renovate the ATR Building, the Purity Bakery Building in South Minneapolis and the Nicollet Island Building. He has an eye for places on the cusp of urban renewal. He doesn’t care much for the gentrification that ensues once he sells a property, but he loves reshaping the raw, industrial interiors of these historic sites. His engineering background allows him to see what others do not and to be an artist in his own right.

_________________________________________________

What architect John Kerwin sees in Red Wing’s Maltery Building is an 80-unit building, with space for restaurants, underground parking, and working studios where tourists can observe artists at work. Now he just needs to convince city leaders to see it too.

_________________________________________________

What he sees in Red Wing’s Maltery Building is an 80-unit building, with space for restaurants, underground parking, and working studios where tourists can observe artists at work. He concedes that his for-profit status means that many sources of funding are closed to him. So, Kerwin is asking Red Wing for $100,000 interest-free loan to help make his vision for these artist lofts a reality. In return, the city will have a place where Anderson Center graduates can continue to live and work in the area.

Robert Hedin loves the idea. “It could be a cornerstone of the renovation of the riverfront area,” says Hedin. The Anderson Center founder advises Kerwin to be tenacious: “I’m very, very hopeful. He’s got a great vision and the obstacles are titanic, but he seems to be a forthright visionary. It would be a great addition and would bring thousands of visitors.”

Kerwin’s plans have a number of supporters on the city council and among downtown business owners, but progress seems to be wearing heavy boots. The RWAA Gallery sits at the base of the hulking old Maltery. Dan Guida, RWAA’s director, says the association is impressed with Kerwin’s plans, but doesn’t have the resources to become a funding partner. He agrees, “it would be a great addition to Red Wing,” but then, he hesitates. “Because [progress] has been quite slow, people are anxious [and ask], is it really going to happen?”

“I have absolutely no artistic ability,” Kerwin confesses as he stands in the Maltery’s demonstration loft. The space is complicated—instead of walls, the loft is divided into floating platforms. The fully furnished apartment includes a kitchen, bathroom, and fireplace at the bottom level; there’s an office, living room and observation deck-style section above. The two-window view over the Mississippi could easily suffice as the room’s only decoration. Even though I moved down here to a twenty-acre retreat of my own, I feel the stirrings of envy when he tells me his vision is to develop the building into low-income housing for artists, with rents between $350 and $700.

The Torpedo Factory—a like-minded endeavor just outside of Washington, DC in Alexandria, VA—has been a massively successful enterprise for artists and business. They now host how-to seminars about architectural recycling, and Kerwin attended the three-day event. Then, he flew the Torpedo Factory architects to Red Wing. They liked what they saw.

Ed McMahon of the Urban Land Institute says the prettier a city is, the more dates it gets. McMahon’s message is similar to that of Richard Florida: court the creative class if you want business. When McMahon did a presentation on the topic for Red Wing at the Sheldon Theater, city and business leaders came away inspired. Richard Florida points to a few prerequisites for cities that don’t want to jump the shark: a good educational institution, an open-minded community, and a high percentage of gay and lesbian residents.

Personally, I think Red Wing seems more likely to let squirrels move in.

Becker, Hedin, Kerwin and Guida believe Red Wing is a perfect candidate for that sort of extreme makeover. Carol Duff, who redid the building that now houses the Chamber of Commerce and her restaurant, Oars D’oevres, is also a supporter. For now, Kerwin is working his way down an extensive and somewhat discouraging 24-item punch list of paperwork from the city.

I know one thing: Red Wing should have hired a professional metaphorian like me. I might have advised against their choice to scatter painted four-foot-tall cement boots around the city as an expression of Red Wing’s creativity.

_________________________________________________

I know one thing: Red Wing could have used the advice of a professional metaphorian like me before deciding to let civic boosters scatter painted boots around the city. I might have advised against the idea of using four-foot-tall cement boots as an expression of Red Wing’s creativity.

_________________________________________________

Fine Line Drawing in Stockholm

In contrast to Red Wing, Stockholm, Wisconsin artists are happily burning their work. City leaders are happy to see it go up in flames, and thousands come to town to watch. In fact, the artists expect many more next year. Stockholm is earning a reputation as the town strong enough to burn its effigies.

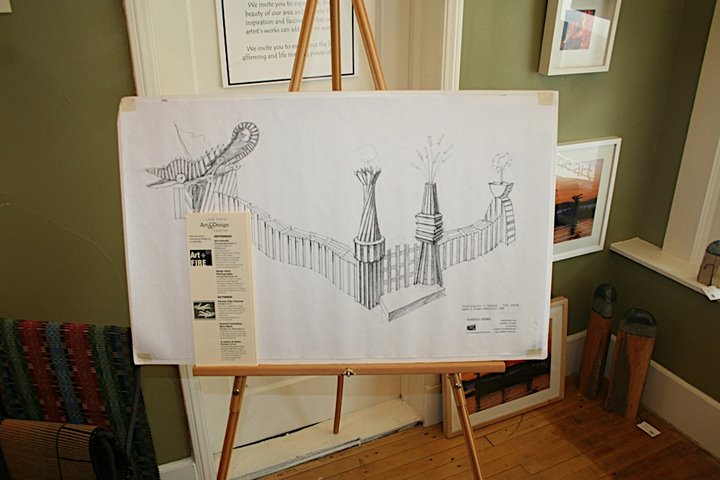

Art+Fire is a community project begun last year by Andrea Myklebust and Stanton Sears. The affair is a strange and wonderful gathering of people grilling brats next to their RVs, a handful of fire dancers, and people in Renaissance Festival garb. As the sun sets, a huge wooden dragon sculpture on a thin jetty in Lake Pepin is lit up with blue spotlights. Little kids sit enthralled, old folks in folding chairs are smiling at the spectacle while teenagers huddle together, taking snapshots with their cell phones. Sculpture students from Macalester light the dragon on fire. An hour later, it is gone. Across the railroad tracks in town, business was brisk all day. The new Stockholm Pie Company stayed open until 10:00, when they sold out of owner Janet Garretson’s homemade pies.

The entire project went from idea to ashes in only one year, and next year’s festival looks to be even more popular than this one.

Wandering through the crowd of locals that night, I remembered being in the back of the car when my parents would drive across the bay to Oakland or Berkeley. I would anxiously wait for the wide turn on Bayshore Freeway where I could see, in a marshy stretch along the water, dozens of figures made of driftwood and scrap. Through the years I watched as figures of animals, people and structures spontaneously and anonymously took form and slowly succumbed to the tides. They were mysterious and awesome and I wondered about them for hours. Today trendy, expensive Emeryville sits on top of the paved over mudflats. Those childhood memories left me struck by a realization: I had found my new home in Stockholm. Everything I loved about the Bay Area of my youth was right here.

STOCKHOLM

Every Tuesday is pizza night in Stockholm. No one calls A To Z Pizza by that name, it’s simply the Pizza Farm. We all gather—locals, visitors from the marina or the city—and blankets are set out on the big lawn surrounded by tall trees. The pizza is completely hand-made with ingredients (including the sausage, chicken, and beef) grown on the farm in all its organic glory. The herbs grow in soil fertilized and de-bugged by hens in a mobile chicken-wire cage. The goats and cows look placidly at the children and tourists, and everyone waits for the gourmet pizzas to emerge from the outdoor brick pizza oven. There are no drinks served and no trash cans. It’s bring-your-own and carry-your-own, and on Tuesdays, after a long week of solitude, or labor, the Pizza Farm is the most beautiful place in the world.

Stockholm doesn’t have a school yet, but the community seems poised for greatness. It has a successful and growing gay population; women own a majority of the businesses and there’s a strong progressive streak in the town’s political leanings (Obama buttons were in evidence everywhere at the Art + Fire burn last month). Alan Nugent and Steve Grams came to Stockholm from Minneapolis about seven years ago. They designed and built their home on nearby Bogus Creek and opened Abode, a high-end home furnishings storefront, gift shop, and gallery. Last month, they also bought The Good Apple, which now completes their ownership of the entire building. The upstairs is a huge, gleaming, empty space and everyone is looking forward to what the two have in mind.

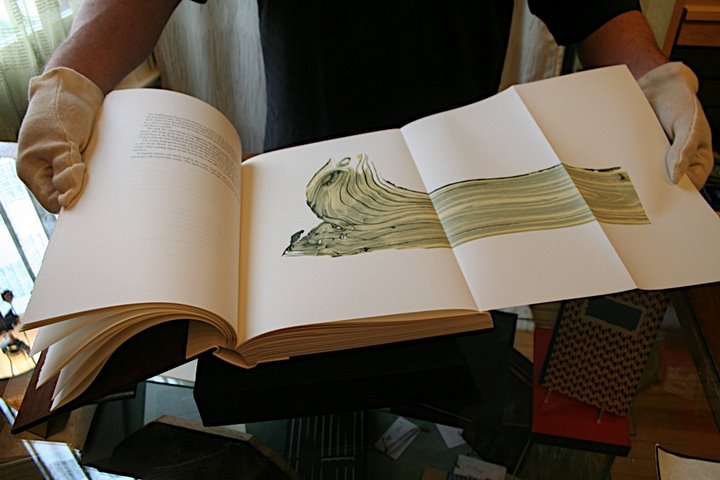

It’s in Stockholm that I’ve found the community of artists I was looking for in this area. The Abode Gallery is a wonderland of local talent. Inside you’ll find David Culver’s granite and wood “pencils,” as they’ve been dubbed, Gaylord’s Schanilec’s prized wood engraving and print making work (his latest numbered edition is available at Abode for $7,500). You can even pick up something by local bestselling author Mary Logue: she sells scarves hand-dyed with local berries, flowers and bugs. Up the street Allison Lisk sells flowers and French-inspired gifts at Clementine, though she continues her duties as the official “Florist to the Palais de Versaille Garden Society.” (Lisk will also be opening a new shop in partnership with Greg Norton, who has a new wine market next door to the massively improved new Norton’s Restaurant in downtown Red Wing.) Six miles south of Stockholm, in Pepin, is another of my favorite places—the ironwork shop of Tom Latané. He’s a true craftsman, working year-round in front of a roaring fire in a small room at the back of T&C Latané, the shop he owns with his wife, Catherine. His iron creations are mind-bogglingly delicate and revive centuries-old design inspirations. Nearby is an optimistic institution which benefits from unusually strong local support, the Pepin Arts Center. Then there’s Rick Vaicius, the kind of fanatic that can spin gold out of straw. He has begun a film festival in a tiny storefront around the corner from The Harbor View, the world-class restaurant and BNOX, the crown jewel of fine jewelry shops in the Upper Mississippi region.

There’s something strange in the middle of all this. It’s in an unnamed patch of meadow in a lightly populated island area between Minnesota and Wisconsin. In the grass and weeds is a giant horse statue, made from chicken wire and other recycled scraps. The horse is rapidly losing its flesh to the elements, revealing the bare but towering skeleton beneath. I don’t know whose horse it is and I don’t much care. To me, it says everything about the creative life down here. Art begets art, which begets life, but the wary villagers have to open the gates and invite the stranger in.

About the author: Sari Gordon is a professional writer.